Who Was the Best Fed Chair? And How Does Jerome Powell Compare?

Unless he’s renominated by President Biden, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s term will expire in February of 2022. Historically speaking, every modern chair of the Federal Reserve has been renominated by the successive president of a different party (often several times) save for one.The only exception is Powell’s nomination in 2017, when President Trump nominated him over incumbent Fed Chair Janet Yellen, who was nominated by President Obama four years prior. But as the White House mulls whether to renominate Powell, it’s an effective moment to understand his tenure and evaluate his performance relative to that of his predecessors.

Since Powell took his position in February of 2018, his turn at the helm has been defined by three major economic developments. The first of these was to continue applying the levers of monetary support in what was already a hot economy, complemented by the Trump administration’s ill-timed and disappointing tax cuts in 2018. This aggressive approach manifested in incredible economic gains: employment grew, unemployment dropped to its lowest level in 50 years, and wages leapt for the lowest-paid workers. The thesis that monetary policy should continue to run hot in a strong economy in order to make up for the losses during the economic stagnation of the last decade and lift the economic tides at all levels proved an astute one.

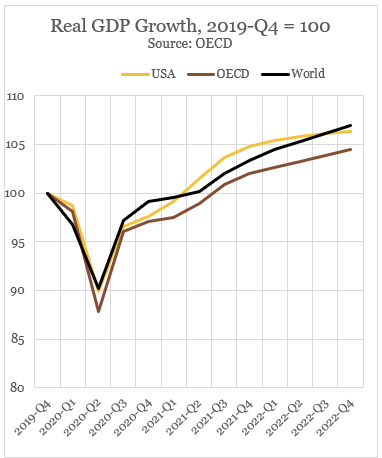

The second development was that of the COVID-19 pandemic, in response to which the Fed cut interest rates and provided extended forward guidance that rates would remain low, began purchasing high levels of securities to prop up the economy, relaxed regulatory requirements to encourage lending and liquidity, administered new loan facilities for small and medium-sized businesses, provided dollars to other country’s central banks at reduced rates to ease strains on the international financial system, and directly lended to state and municipal governments (something it resisted doing during the financial crisis and Great Recession). These actions expanded the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and — when combined with the massive federal stimulus — resulted in the US economy’s growth outperforming comparable countries in 2020 and 2021, which is forecast to continue outperforming through 2022.

The third and final major economic development of Powell’s tenure was the alteration in policy that began in 2020 to aim “to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time” rather than target 2% inflation directly. This apparently minute shift in its monetary policy is a watershed moment for the Fed, arguably the biggest policy shift in 40 years. This is because inflation has struggled to stick to its 2% target in the 21st century, not because it was too high… but because it was too low. Yes, that’s right readers — although we live in a world where inflation is overemphasized and shoved into our politics, it likely isn’t a major economic crisis. Our inflation has chronically underperformed for years. So the reason this new policy framework from the Federal Reserve was so groundbreaking is it indicates they will allow inflation to exceed 2% so that it can average 2% in the long run. That’s part of the reason the Fed is not raising much alarm about inflation. Prices may be higher than expected, but a burst of what is likely transitory inflation after years of prices rising too slowly is not cause for panic and can be (if managed correctly) a blessing in disguise.

This is a lot in a four year term as chair but it points to Powell’s competence and his effectiveness as a stable guide during the economic crises in the last two years. But, as he faces evaluation for another term as chair, how does his record stack up to that of his predecessors who weathered everything from a near-collapse of the financial system, stagflation, bank bailouts, and extended unemployment?

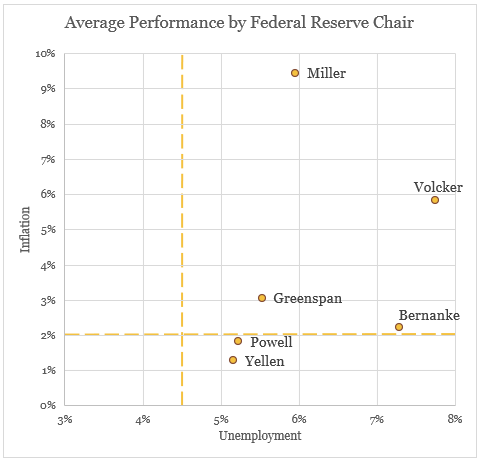

The best numerical measure by which we can judge Federal Reserve chairs is by the metrics they are charged to meet. Since 1977, the Federal Reserve’s “dual mandate” has been maximum employment and stable prices — which they’ve targeted at around 2% inflation and an ever-shifting rate of unemployment that depends on economic circumstances, but likely hovers around what is called the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (or NAIRU), the lowest rate of unemployment before more labor gains would translate into inflation. This is based on the theoretical natural rate of unemployment, which is the expected unemployment rate when the economy is in a steady state of full employment. The estimated value for maximum employment is around 4-6% unemployment, and the current estimate is unemployment around 4.5%. This may sound high — it means millions are unemployed after all — but that’s actually normal. Even in a healthy labor market, there will be frictional unemployment as workers transition between jobs or enter the workforce and structural unemployment as new technologies force some businesses under and industries adapt over time. Because inflation has run so low for so long, even when unemployment was low, we’ll go with a conservative estimate for the ideal unemployment rate at around 4.5% and stick to the 2% target for inflation.

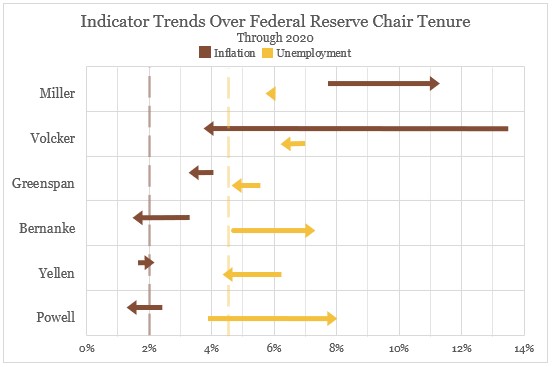

Since 1978, the first year after the dual mandate was set in 1977 as well as the first year of Fed Chair William Miller, there have been six chairs of the Federal Reserve: Miller (1978-1979), Paul Volcker (1979-1987), Alan Greenspan (1987-2006), Ben Bernanke (2006-2014), Janet Yellen (2014-2018), and now Jerome Powell (2018-present). We can compare them by two metrics, averaging the annual inflation rate and unemployment rate in each year they were chair for a majority of; and the trend in annual unemployment and inflation from their first year to their last.

Miller, historically considered one of the worst Fed chairs (which is not surprising given he had no serious economic background), performs very poorly in all of these metrics. High inflation and high unemployment (that’s what we call stagflation!) hamper his average performance, and his trendline sees the largest increase in inflation of any of these chairs. These missteps sully the average record of the succeeding Paul Volcker, who ultimately tamed the “Great Inflation” but still has, on average, high inflation over his term. But Volcker was, of course, a legendary Fed chair. He chose to spike interest rates to force a recession in order to kill the 1970s inflation and successfully brought inflation down nearly 10% over the course of his tenure, as the trendline chart shows. But average unemployment remained high (in part, intentionally, as he prioritized inflation over employment) under Volcker, and he failed to significantly bring that number down.

Next up, Greenspan, who gets very close to meeting both the inflation and unemployment targets on average under his tenure, and brought both numbers closer to the goal from when he took the post in the late 1980s until his retirement in the mid-2000s. After 18 years as chair under four presidents, he left office at an opportune time considering what would economically come to bear in the late-2000s (which he may or may not have had a role in perpetuating, as even he has effectively admitted).

Then comes Bernanke, possibly the most important person in the 21st century so far. You may hate him, but this expert on the Great Depression emerged like a man out of time to avenge the American economy and saved the nation’s, the world’s, and your financial future. Inflation collapsed and unemployment shot up as a result of the financial crisis and Great Recession, but Bernanke steered the monetary instruments of the world’s most important economic power towards a worldwide recovery. His trendlines and the high-level of average unemployment across the recession and its slow recovery do not do him justice. It’s truly difficult to adequately compare him, it’s like comparing any president to Abraham Lincoln — none of them had to deal with something like that. Paul Volcker may be like the greatest hitter of all time, but Bernanke is the pitcher who, as an earthquake threatened to swallow up every team in the Major Leagues, held the earth together with his bare hands.

After an intense eight years on the job, Bernanke retired and Janet Yellen, the first woman to chair the Fed, took the helm. When she took over in 2014, the economy was well into its recovery and, based on both our trendline and averages, she probably takes the cake on metrics alone. Over her four years, she steered inflation and unemployment almost exactly to their targets, and she can claim the lowest inflation and lowest employment on average of any modern Fed chair. This made the decision not to renominate her a historic anomaly (and, reportedly, incredibly petty) but she would go on to break another barrier three years later as the first woman to become Secretary of the Treasury under President Biden. And, considering what her successor would go through, her record now remains untarnished.

Powell, as we unpacked at the onset, has served as chair under far more calamitous economic headwinds, but his performance is nonetheless admirable. The unemployment average was low through his tenure, as was inflation. Our data for our metrics only goes through 2020, which makes Powell’s trend line look worse. Unemployment of course shot up to an average of around 8% that year, and average inflation in 2021 will almost certainly be high. Indeed, should Powell’s term end in 2022, he will be the only modern Fed chair for whom both inflation and unemployment were higher at the end of his term than they were at the onset.

Nonetheless, Powell’s renomination seems likely as it would align with three key objectives of the Biden administration. The president has put emphasis on restoring the traditions and norms of American government in contrast to his norm-violating predecessor. Renominating, as is the historical norm, Trump’s Fed chair would do exactly that. Biden has also built an administration on expertise and experience, leaving key policy decisions to the tried and tested experts. Powell and Yellen maintain a strong relationship and the two are undeniably experts in the field of monetary policy. Finally, the administration has sought to provide stability in leadership during tumultuous times. Unseating a Fed chair who has performed admirably during a crisis would be a sign of panic and threaten the independence of the Federal Reserve. That alone is reason to keep Powell in the job, but the chairman’s merits stand for themselves. He ought to have the chance to finish what he started, see the economy out of the pandemic, and go down in history as one of the greats.