The Midwestern Reality: Pennsylvania, the Bisected Keystone

This is the fourth piece in our series of six features on the Midwestern Democratic decline where we’ll be diving into consequential parts of the Midwest and the prevailing headwinds faced by the Democratic Party in the region. We’ll use each part to build on a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted relative to the nation at large, and demonstrate how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.

You may be asking yourself “is Pennsylvania even part of the Midwest?” That’s a fair question. It’s the only state we’re covering in this series that is not within the Census’ “Midwest” region. Even The Postrider’s preferred map for political and economic analysis by region, the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ regions (which splits the US into eight regions, and does not include Delaware and Maryland in the South, unlike the Census), includes Pennsylvania in the “Mideast” with New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. But the answer as to whether Pennsylvania counts as the Midwest is probably that it is, at least in part. Philadelphia is a Mid-Atlantic city in kind with Baltimore, New York City, or Washington.It’s a pretty major stop on the Northeastern Regional Amtrak line! But Pittsburgh, which is located in western Pennsylvania, is physically closer to cities like Cleveland, Columbus, and Detroit than it is to Philadelphia, which is in the southeastern corner of the state. That Pennsylvania is an amalgamation of at least two different lifestyles, economies, regions, and cultures is evident in its sports teams, voting habits, and even in regulatory policy, as the Federal Reserve splits the state in two for its purposes.Some have argued Pennsylvania falls into three different regions: a Midwestern one, a Mid-Atlantic one, and an Appalachian one. In an attempt to be inclusive, and because its shift to the right was critical in the 2016 election and it was dubbed “the most important state on the map” for the 2020 election, we are counting Pennsylvania as at least partially a Midwestern state for the sake of this series.

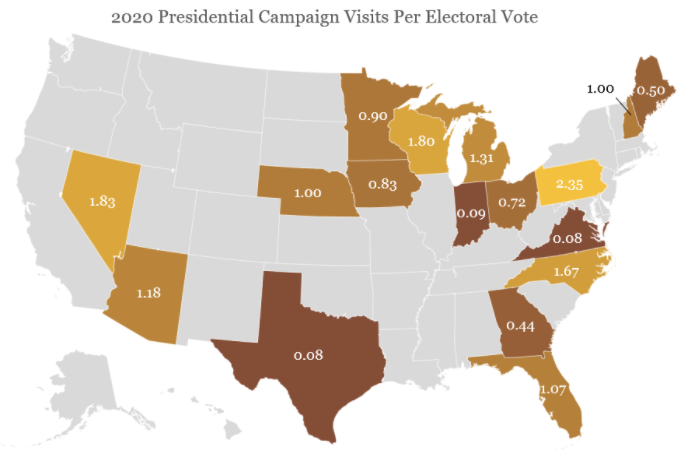

And what a Midwestern state it is. Tied with Illinois in terms of electoral votes as the largest Midwestern state, torn between a liberal East Coast and an insurgent freshly-conservative Rust Belt Midwest, the Keystone State received 47 visits from the 2020 presidential campaigns, more visits than any other state did. Even on an electoral vote basis, it received more visits per electoral vote than any state in the country, lending credence to the premise that the two presidential campaigns believed it to be the critical state. Election forecasts backed this up, identifying Pennsylvania as the most likely tipping-point state, which refers to the state that provides the 270th electoral vote to the presidential election winner. This intense competition followed what was, like Michigan and Wisconsin, over two decades of voting for the Democratic presidential candidate. That is until 2016, when Trump narrowly carried all three supposed “blue wall” states, propelling him to victory in the electoral college.

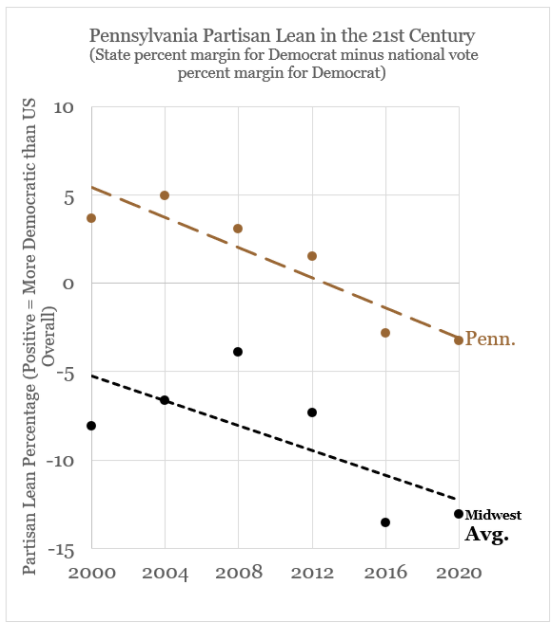

2016 marked the first time since 1948, when Dewey famously did not defeat Truman, that Pennsylvania’s presidential election margin was more Republican than the national margin. In 2016, by narrowly going for Trump by 0.7% while Clinton carried the national popular vote by 2.1%, Pennsylvania was 2.8% more Republican than the nation as a whole. This seems like a dramatic turn, and it sort of was, but it was also predictable — and predicted.

“The Clinton Campaign Seems to Think Pennsylvania is in the Bag… But it shouldn’t bank on it” ran a foreboding FiveThirtyEight headline in June of 2016. “Many Democrats take Pennsylvania for granted because it hasn’t voted Republican in a presidential election since 1988. But in 2012, its margin for President Obama was just 5.4 percentage points, equal to his margin in Colorado and less than his margins in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada… Moreover, unlike those four states, Pennsylvania has trended toward Republicans over time, thanks to its older, whiter and more working-class electorate,” wrote David Wasserman in the piece, following up by noting that “so far this year, 73,543 Democratic registrants have switched to the GOP. The switchers mostly live in heavily white, working-class counties, and most did so in advance of the April 26 primary, presumably to vote for Trump.” Trump would end up winning Pennsylvania by less than 45,000 votes.

60 of the state’s 67 counties, all in the western portion of the state outside of Philadelphia, trended more Republican over the Obama presidency. The warning signs were there for Democrats, but they may have learned the wrong lessons from this dramatic turn of fortunes in Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania is about 76% non-Hispanic white, making it nearly 16% more white than the United States overall. It slightly underperforms the nation in terms of percentage of the population with bachelor’s degrees (31.4% of 25-and-older Pennsylvanians) and overperforms it in terms of unionized workers (13.5% of wage and salary employees in the state). Like Minnesota, the blue collar workers were historically Democratic-leaning, but as their numbers have declined and they blamed some Democratic policies on environmental and trade issues for worsening prospects in the state, they became increasingly Republican-leaning. In whiter and less-educated counties of the state (almost everything that is not Philadelphia and its suburbs) this shift was particularly pronounced. This is not quite a far cry from Democratic political consultant James Carville’s legendary adage on the Keystone state, which is often summarized as “Pennsylvania is Philadelphia and Pittsburgh separated by Alabama,” but even this summation is out of date. Everything around Pittsburgh’s Allegheny County has become redder too, making it one lone patch of blue in a sea of red. Even in the elections of 2000 and 2004, Democrats won counties neighboring Allegheny, not so much now.

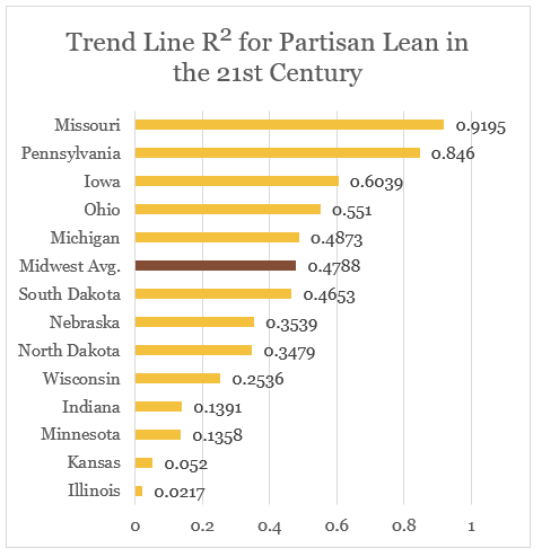

As with many of its Midwestern “blue wall” counterparts, Biden’s win over Trump in 2020 disguised an alarming reality for Democrats: Pennsylvania was getting even redder. In 2020, it went for Biden by 1.2%, making it 3.3% more Republican than the rest of the country, which went for Biden by 4.5%. Though it has not moved to the right as fast as some other Midwestern states like Iowa and Ohio, its trend has been among the most precise.

Among Midwestern states, Pennsylvania has the second best fit trend line, showing very little variation across time based on the R-squared value of the trendline for each state’s partisan lean in this century. 85% of the variance in Pennsylvania’s partisan lean is captured by this march of time, a remarkably consistent trend directing it towards its current status as a Republican-leaning state. This is unusual, because differences in local conditions, events within the state itself, or candidates that have particular ties or appeals to the state (like, for example, “Joe from Scranton”) would cause some sharp variations in partisan lean from one cycle to another. We’ve averaged these fluctuations using partisan lean over the 21st century to show these trends across the Midwest over time but the fact that Pennsylvania’s trendline itself is 85% effective in capturing that variation in and of itself is damning and, well, predictable! It’s a huge state that gets a lot of attention: it takes a lot of effort to move a large enough share of voters in the state to make a difference. We’ve talked a bit about this in our Running Mates project, revolving on home state advantages in selecting a vice presidential candidate. It’s well documented that vice presidential candidates can provide an electoral benefit for the ticket in their home state, but that benefit tends to be small and gets stronger as the state becomes smaller. In other words, all other things being equal, a vice presidential candidate from New Hampshire will provide a larger difference to the margin in New Hampshire than a vice presidential candidate from California would provide to the margin in California. Unfortunately for Democrats, Pennsylvania’s consistency means it will be harder to cater specifically to local conditions that can make Pennsylvania buck this persistent trend. It is not particularly elastic in this way.

Named the Keystone State for its centrality in the early United States, bridging and binding the North and South together as it stretched to the nascent Midwest, Pennsylvania is a microcosm for the choices the parties and regions must take over the next few decades. Embracing urbanites and suburbanites may help the Democratic Party run up its margins in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, but as blue collar voters flee the party and are supplemented by white collar and high-education ones, they’re going to need to push up these metropolitan margins by more and more. That’ll be a tough proposition in a state that is growing much slower than the rest of the nation.

But Pennsylvania wasn’t necessary for Biden to win anyway. Even had he lost it and Wisconsin — the only other Midwestern state closer than Pennsylvania — he would have won the election. Democrats’ preoccupation with winning the Keystone State may not serve them well in the long run, but it’s possible that this Midwestern decline for their party has illuminated paths not thought possible a decade ago. Paths where diversity and education levels have increased and populations have grown, perhaps even hinting at what parts of the Midwest could yet buck the trend.