Democrats Are Ignoring the Midwestern Reality

This is the first and introductory piece in our series of six features on the Midwestern Democratic decline where we’ll be diving into consequential parts of the Midwest and the prevailing headwinds faced by the Democratic Party in the region. We’ll use each part to build on a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted relative to the nation at large, and demonstrate how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.

“The Midwest Holds the Key for Biden.” So ran a New Yorker headline on Election Day, 2020. And so went conventional knowledge ever since 2016, when Trump broke the so-called “blue wall” — the set of states that consistently voted for Democrats… until they didn’t. The problem with the headline is that it wasn’t really true. Biden didn’t need to dominate the Midwest, and Democrats need not rely on it as they used to. Because the party has changed, the Midwest has changed, and America has changed.

There were only six states that were not won by over 2.5% in the 2020 election. This excludes Michigan, which Biden won by a little under 3% and Florida, which Trump won by a little over 3%. Without these six states, but including Florida and Michigan, Biden held 243 electoral votes and Trump held 217. Biden didn’t need Wisconsin or Pennsylvania. He didn’t need North Carolina or Nevada either… he actually only needed two states that — unlike these four — hadn’t voted for a Democrat for president since the 1990s: Arizona and Georgia.

Unusually, these two Biden pickups from the “red wall” occurred in an election facing off against an incumbent president. It’s been said before and it’s worth saying again: defeating an incumbent president is a difficult undertaking in a normal election, doing it with one hand tied behind your back, barely knocking on doors while your opponent rouses a passionate band of supporters unafraid to do the same, is astonishing. But underneath this amazing performance (and I nonetheless encourage you to overrate Biden’s performance relative to the prevailing thought that he “narrowly” won or was “lucky”How a candidate who almost always polled at the front of the Democratic primary field and also consistently polled ahead of his general election opponent winning an election could really be called “lucky” is a bit questionable…) is a creeping reality. That reality is that Democrats’ wins in the Midwest this cycle are overshadowing the party’s decline in the region, and putting so much emphasis on their declining demographics at the expense of the diversifying Sun Belt is a mistake.

The Midwest is a region that has moved against the Democratic Party and proved particularly prone to Trumpian sentiment. Formerly progressive Wisconsin has turned into a rancorous cesspool of partisanship. Electoral bellwether Ohio, which voted with the winning presidential candidate for over half a century, is now a bellwether only for Trumpism. Even Pennsylvania — which exists in a half Midwestern-half Eastern limboYou could easily make a case that Pennsylvania really reflects three regions with different political persuasions: the Midwest, the Mid-Atlantic, and Appalachia. An entire article could be written about how Pennsylvania fits into the United States regionally; even the Federal Reserve splits the state in two, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has profiled its division before as well. For the sake of being inclusive rather than exclusive, we will include Pennsylvania as at least part of the Midwest, if not fully Midwestern. — has devolved into a striking urban-suburban-rural divide, as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh are surrounded in an ever-expanding sea of Republican counties. Readers may protest that Minnesota has voted for the Democratic candidate longer than any other state in the country, notable for the fact it was the only state not to vote for Ronald Reagan in 1984, but Democratic decline is visible there as well, a slow drip rather than the hemorrhage you see in places like Iowa or Missouri.

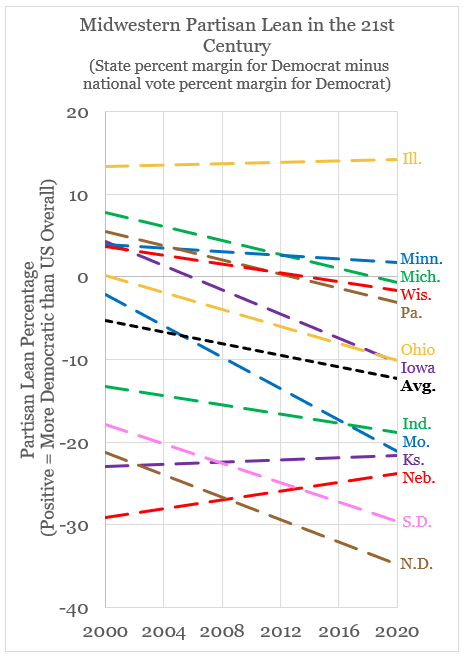

Across the entire Midwest, which for the sake of this series will include every state categorized by the Census Bureau as “Midwest” with the addition of half-Midwestern Pennsylvania (see footnote above), only three of these 13 states have become more Democratic relative to the nation as a whole. Disappointingly for both parties, these are the solidly Republican states of Kansas and Nebraska (both of which last went for a Democrat in 1964) and the solidly Democratic state of Illinois (which, like California, last went for a Republican in 1988). Every other Midwestern state, from North Dakota to Michigan, and Missouri to Wisconsin has marched in an increasingly conservative direction.

That this hasn’t been evident is a sign of our times and of entrenched partisanship. Many of these states are close states, so they get more attention when they flip one way or the other and less attention when they slowly change over time. Barack Obama won Wisconsin by almost 14% over John McCain in 2008; an election which he won nationally by over 7%. This means that Wisconsin was 7% more Democratic than the nation as a whole in 2008. But when Joe Biden won Wisconsin by less than 1% in 2020 despite winning nationally by 4.5%, it was easy to forget that this indicated Wisconsin was now 3.5% more Republican than the nation as a whole, a massive swing over 12 years. This pattern, as we’ll unpack, is fiendishly persistent across the Midwest. Wisconsin — like Michigan and Pennsylvania — just happens to get the most attention.

As we’ll explore in this series, the Midwest underperforms the nation in education levels and diversity. It’s more racially segregated and rural than most of the United States, and it represents a decreasing share of the country’s total population overall. It is an area more prone to crime and especially susceptible to militia movements. The region is sentimentalized by traditional values, wherein the “normalcy” with which the Midwest is viewed is associated with antiquated notions of masculinity, whiteness, and straightness. Many of these attributes are related to each other; lower education levels lead to increased crime and militia activity, for example. Over the course of this series we’ll explore these traits and we’ll look at the states in the region which have veered away from these trends to underscore what can be done differently. The romanticization of a region plagued by social inequities and long standing decline panders at the expense of America at large and of those living in the Midwest. By failing to acknowledge the region’s political reality, Democrats are kidding themselves by staking their future electoral prospects there, and Republicans are enabling this decline by failing a region that has turned to them.

By illustrating how these states and this region have shifted over the 21st century relative to the United States overall, evaluating the exceptions that prove the rule, and diving into why this change has occurred, we can paint a picture of a region that is slipping away from one party. And perhaps more importantly, we can provide evidence for alternatives. States change, parties change, and regions change. No longer the bastion of Democratic power and increasingly devoid of the “Midwestern nice” it has prided itself on, no region better illustrates the divisiveness and dividing lines in American politics than the Midwest. If America’s government is ever going to stop sacrificing itself at the altar of the Great Lakes and its unrepresentative minority, it’s time to time to move on. That is the case we will beat to death, and then some, in this extended series.

Starting next week, we will be diving into the most consequential parts of the Midwest and focusing on how they have shifted relative to the nation. In each part, we will focus on the prevailing trends in education, racial diversity, employment, and urbanization, building a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted over the 21st century and demonstrating how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.