How Our 2024 Republican Vice Presidential Power Index Works

If there is one particular niche we are known for here at The Postrider, it is our religious coverage of vice presidents, the vice presidential selection process, and what goes into a strong vice presidential pick.

One of our notable claims to fame was a tool we developed last presidential election cycle, for the 2020 Democratic primary and on, which we dubbed the “Vice Presidential Tracker.” With an extensive methodology, lots of data, and some serious grit, we built out a model that would determine the strength of any presidential ticket based on a given top-of-the-ticket nominee. By running data on an array of potential vice presidential picks through a model that also considers data pertinent to the presidential nominee, we can determine the relative strength of a given ticket overall and make a statistical case for who a given nominee should select as their running mate.

Though not predictive in nature, our tool identified then-California Senator Kamala Harris as the strongest possible running mate for the ultimate Democratic nominee, Joe Biden. Biden, of course, did end up selecting Harris as his running mate, and is gearing up for reelection with her again (anyone who seriously believes he might or even should pick another running mate for 2024 should not be taken seriously as a political reporter).

Almost four years later, after digging through binders of old notes, we’re back to do it all again, this time for the Republican ticket. As our methodology unpacks, this poses its own unique considerations due to the more homogenous makeup of the Republican electorate and base, but some careful research and statistical extrapolation mean we were able to largely adopt the same successful 2020 model to the 2024 Republican veepstakes – enjoy!

Methodology

Candidate Inclusion

Presidential candidates are included if they are actively running for president and have met one of the following two qualifications:

- They participated in a debate

- They have ever had a polling average of 1% or greater

VP Inclusion

Potential vice presidential choices are included if… you want them to be! So long as they are eligible to be vice president (they have not served more than six years as president, they are at least 35 years old, are a natural born American citizen, and must have lived in the United States for 14 years), they can be added to the Power Index. Our Editor-in-Chief and I put together a list of just over 30 names who we thought were particularly likely to be on a long list for any potential Republican presidential nominee. If you’d like us to add someone to the VP Power Index, shoot us a note at at contact@thepostrider.com and we’d be happy to oblige!

VP Score

On to the nitty gritty, here’s how an individual potential VP score is determined. It starts with the nominee, and takes into consideration their:

- State of residence

- Gender

- Race (this is a binary, a score of “0” if they are caucasian; a score of “1” if they are any other race including Latino)

- Years of federal government experience (ex. as a congressman, senator, cabinet secretary, vice president, high level military command, etc.)

- Years of non-federal government experience (ex. as a governor, state representative, general military service, etc.)

Taking that data for a given nominee, it runs through every single potential VP choice, for whom the data is their:

- State

- State’s number of electoral votes

- State margin, or the partisan lean of their state plus the generic ballot (positive number is leaning Republican, negative number is leaning Democrat; this is taken from FiveThirtyEight’s open source partisan lean data. The generic ballot lean (courtesy currently of RealClearPolitics, later FiveThirtyEight, once their data paints a clear average), which is the degree that national headwinds favor Republicans in general is then added to this, So, for example, if the state has a lean of -2 (2 points more Democratic) and the generic ballot has a lean of 5 (5 points towards the Republicans), then the state margin is 3.

- Gender

- Race (this is a binary, a score of “0” if they are caucasian; a score of “1” if they are any other race including Latino)

- Reelection year (if you are currently in office, this is the next year you are up for election if you are not currently in office, or if your state allows you to run for two offices at once, this number will be “0”)

- Years of federal government experience (ex. as a congressman, senator, cabinet secretary, vice president, high level military command, etc. Note that if they are currently in office this will include all of 2024 as a year, so a representative first elected in 2012 that took office in 2013 and would presumably serve until January of 2021 will have 8 years)

- Years of non-federal government experience (ex. as a governor, state representative, general military service, etc.). Combining years of federal experience with years of non-federal experience results in total experience.

- Minimum viable office (this is a binary, a score of “0” if they do not meet the “minimum viable office” standard of more than 6 years as a member of the House, any service as a Senator, cabinet member, or military command, or as a governor, a score of “1” if they do)

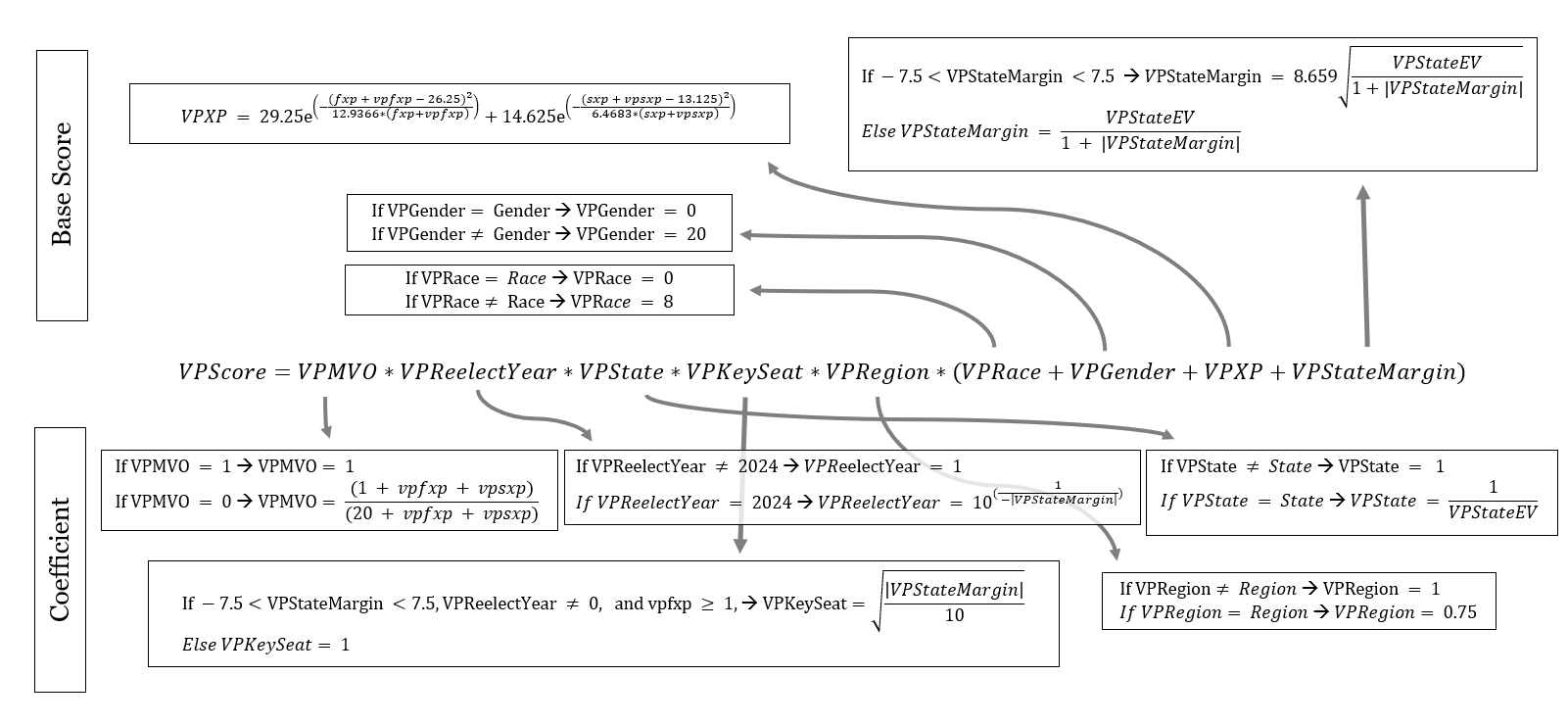

With all the variables, it will run all of the possible vice presidential picks for a given nominee, and determine a “VP Score”, which is the strength of the ticket based on an equation that is easiest to describe by breaking it down into two key parts: the “coefficient” and the “base score.” The coefficient is the values multiplied together which serve to lower an overall score; the base score provides increases. The base score multiplied by the coefficient gives the final score. Here’s some more detail on each:

The Coefficient

The coefficient has five components all multiplied together. If you’re familiar with our 2020 Vice Presidential Tracker for the Democratic Party, these will all be familiar – they are unchanged other than the modernization of data (we have one more election – the 2020 election – to expand on our data since four years ago).

VPMVO: This is the minimum viable office adjuster. If a VP choice meets the standard, it receives a value of “1” (because this leaves the core score unaffected, this will be the case with all of the variables in the coefficient). If they do not, this value is calculated as (1 + total years of experience) / (20 + total years of experience). This 1/20 base value was selected because out of the 20 vice presidential picks (excluding incumbent vice presidents) since 1968, only one (Geraldine Ferraro, Walter Mondale’s pick in 1984) did not meet this qualification. We use 1968 as the base year throughout this project because it represents the fundamental turning point in how American presidential primaries are carried out in modern times and it lets us start with no incumbent president running at the top of the ticket. Because total experience is added on to the numerator and the denominator, this number can reasonably increase if there is enough lower-level experience, but always remains a detractor.

VPReelectYear: If a potential VP is not up for reelection in 2024, choosing not to run for reelection, they’re a member of the House of Representatives and in a noncompetitive district (i.e., the district‘s partisan lean is more than 7.5 points either way), or they can run for two offices at once, this has a value of “1”. However, if those do not apply and they’re up for reelection in 2024, then this is calculated as 10 to the power of one over negative the absolute value of their state’s partisan lean. So if the state’s margin is closer, it becomes far less wise to put the candidate on the ticket at the risk of losing their seat (keep in mind, if the generic ballot is closer, they’re also far less likely to win the presidential election as well). However, if the state’s margin is looking like a blowout, this number approaches 1.

VPState: This one seems redundant, but essentially it boils down to this: your vice presidential pick should not be from the same state you are. Pragmatically it’s because the state of the pick does have a small impact and it makes sense to diversify your ticket, and legally it’s because electors from one state are forbidden from voting for two candidates from the same state on their ballot. You’d be forfeiting a given number of electoral votes, possibly ending up with a situation where a president or vice president were elected without the other.If you love political hypotheticals, this almost happened in the year 2000. Both George W. Bush and Dick Cheney were registered in Texas, but Cheney changed his registration to Wyoming before the election. The electoral vote was close enough where this would have deprived Cheney the vice presidency (at least initially) and required the Senate to choose a vice president. If you’re from different states, you get a value of “1” again; if you’re from the same state, then this number will be one over the electoral votes of the VP pick’s state. I do this because it still cuts the score by a lot (the minimum electoral votes a state can have is 3, which still brings it to a total score reduction of two-thirds) but not all states are created equal and technically, having two candidates from California (54 electoral votes) or Texas (40 electoral votes, see footnote above) would be immensely stupid, whereas having two candidates from tiny Rhode Island (4 electoral votes) would be… still pretty stupid, but less so.

VPKeySeat: This attempts to address the strategy in deliberately not picking an otherwise near perfect vice presidential candidate. The logic here is presidential candidates will avoid picking a running mate who would cost them a key Senate seat they are at risk of losing in the future.

Here’s how this works. If a VP choice’s federal experience is at least one, their reelect year is not “0” (this means that they are not running for reelection at all), and their state margin (remember this is the partisan lean plus the generic ballot) is between -7.5 and 7.5 (any race that is within this margin would make it at least somewhat competitive), then this is calculated as the square root of the absolute value of the VP state margin over 10. This allows a great pick to be exponentially weaker if their state’s margin is too close, but doesn’t hurt them too drastically if their state’s margin is safer, while still providing a slight disadvantage in picking them. If this situation does not apply, the score is, once again, a simple “1.”

There aren’t actually any great examples of this in the Republican field of likely vice presidential picks this year, but we’ve left it in the formula because a shift in the generic ballot could kick this in for some people like, say, Iowa Senator Joni Ernst. Iowa is 9.7% more Republican than the nation overall, but if the generic ballot favors Democrats by 5%, then Iowa is considered at least potentially risky enough to slightly ding a potential pick under this metric.

VPRegion: Regional balancing is something most presidential campaigns strive for so that they can claim to be representative of the nation as a whole instead of one particular region. For the sake of this project, we are using the US Bureau of Economic Analysis’ regions, since they are representative of the economically, politically, and culturally similar areas of the country, but remain large enough to divide the nation in eight different slices.These regions are by no means perfect. Alaska has very little in common with California culturally or politically; nor does Florida share a great abundance of economic similarity to West Virginia; but they do pretty effectively capture what the more modern understanding of “regions” seems to be, unlike the US Census Bureau, say, which considers Maryland and Delaware part of the South. Using the BEA regions, we found only two times since 1968 where the president and new vice presidential pick (incumbent tickets are excluded) are from the same region: In 1968, Richard Nixon of New York and Spiro Agnew of Maryland were both from the Mideast; and in 1992, Bill Clinton of Arkansas and Al Gore of Tennessee were both from the Southeast. Though I do note both of those campaigns did go on to win the general election, Nixon-Agnew lost a majority of the states in the Mideast region, and Clinton-Gore only got half of the states in the Southeast region. Conventional wisdom favors regional diversity, and thus if the regions are not shared, the value here will be “1.” But if they are shared, it is reduced to “0.75” to reflect that a campaign could hope to appeal to at least two of eight regions (or 0.25) leaving at worst six of the other eight (0.75) regions off the table by default. Multiply all of these together and you’ll get the coefficient half of the equation to determine the VP Score.

The Base Score

The “Base Score” is where you can find the key difference between the factors which go into this Power Index and the one we produced for the Democrats in the last cycle. It’s no surprise that the constituencies, influences, and interest groups in the Republican Party are distinct from those in the Democratic Party. In 2020, we built our model from scratch using conventional wisdom, academic material, and statistics derived from some unique sources to answer the somewhat icky questions of how much value to give a diverse presidential ticket considering race, gender, and age. Though the Republican Party is far more homogeneous than the Democratic Party, these considerations still matter because the vice presidential selection is made with an eye on the general election rather than the primary. Even so, the composition of the Republican Party is distinct enough from the Democratic Party that their Vice Presidential Power Index deserves some further scrutiny and adjustment.

The base score for the Republican Vice Presidential Power Index has four key components all added together; they constitute the core score that is then reduced by the coefficient. In theory, a perfect candidate would have a base score of 100: 43.875% based on complementary experience (which is a major consideration in selecting a running mate), 28.125% based on the competitiveness and importance of the VP pick’s state (which can help, but doesn’t generally make a significant difference), 20% based on gender diversity, and 8% based on racial diversity. I’ll explain more why these are allocated as such in the individual descriptions.

VPRace and VPGender: If the nominee and the VP choice have the same race value (remember, this is binary), VPRace receives an input of 0. If they are different, it receives an input of 8. If the nominee and the VP choice have the same gender value, VPGender receives an input of 0. If they are different, it receives an input of 20.

I’ll be candid – the need for racial and gender balancing on the ticket is relatively new, so there’s not enough data to make much more than an educated guess as to how much it will matter. My inclination is that race matters about two-thirds as much as gender, because they obviously overlap with each other (there are more women in the country than there are white women in the country). This is imperfect statistical logic and is largely based on our 2020 model for the Democratic Party’s vice presidential selection. In 2020, we surmised there would be immense pressure placed on the modern Democratic Party to have a diverse ticket, and it is common sense that – all else being equal – a ticket with two white men on it is weaker and more alienating. Here, in 2024’s Republican picks, we’re applying the same logic. We don’t yet have the data on betting odds to pull a statistical value from of the odds that their ticket would include a woman, for example, which is how we derived our numbers for the 2020 cycle, so we will – keeping in mind similar discourse currently occurring about the GOP’s selection – be keeping the same allocation of 20% for gender. This came from the regression coefficient from betting data indicating that if the presidential nominee was not a woman, there was approximately 20% more chance that the vice presidential nominee would be a woman.

Approximately 19% of Republican voters are nonwhite, and approximately 47% of Republican voters are women, so we will weigh race by 40% of gender in considering the Republican ticket. This means racial diversity can add 8 points to a Republican ticket (40% of 20) – significantly less important than gender diversity, and far less than we gave it when it came to the Democratic ticket in 2020. But this makes sense: Republican voters are much more racially homogenous, so racial diversity simply matters less to their core constituencies. Their ticket is certainly stronger by virtue of it not being topped by two white men, but we don’t want to overstate this importance and tokenize a ticket either. This provides that balance.

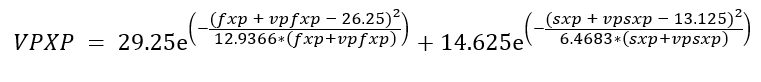

VPXP: Arguably the most complicated and by far the most important measure that increases a ticket’s strength, this composes up to 43.875% of the base score. That’s an oddly specific number, you may note, and that’s because we know that complementary experience and the state margin must add up to 72% of the total score, as gender and race account for a 28% of the score. I allocated experience and state margin by looking at every unique vice presidential pick from 1968 and the combined federal experience with the presidential pick (in years) and how many times the VP pick was from a competitive state.We’re using the same standard as this NPR article, which describes a swing state as any state that had a margin of <5% between the two candidates in any two of the four elections chronologically closest (before or after) a particular election year, as well as the election itself. Mike Pence (Indiana), for example, is not a swing state pick, even though there was one election (2008) in which it was won by a margin of less than five percent. The VP pick was from a competitive state nine times out of 20 unique picks (45% of the time) and the combined federal experience averaged 26.25. I ran descriptive statistics on the combined federal experience in years to find a standard deviation of 12.9366, and went one standard deviation on either side of the mean to find an acceptable level of combined federal experience (that would, under the empirical rule, capture about 68% of all presidential tickets). There are 14 out of 20 presidential tickets with a combined federal experience within one standard deviation from the mean. This implies that experience is about 1.56 times more important in picking a VP than picking one from a competitive state. Since these both must fit into the remaining 72% of the base score, this requires VPXP to be weighted at 43.875% of the base score, and VPStateMargin to be weighted by 28.125% of the base score.

VPXP is calculated in two parts, using the presidential and vice presidential candidates’ combined federal experience and their combined non-federal experience. Recall the average combined federal experience is 26.25 years, and the standard deviation for that was 12.9366, meaning that under the empirical rule, 68% of values must lie within one standard deviation of the mean. The reason it is not just simply one standard deviation below the mean (and continuing to increase the score the more combined years the ticket has) is because there appears to be diminishing marginal returns in having a ticket with too much experience. Otherwise, most presidential tickets would have combined federal experiences well into the 40s or 50s. The experience, instead, more closely follows a normal distribution, where there is an increasing benefit up to a point, and then a decreasing benefit. This is also a good proxy for age, as two candidates on the ticket with 40 years of federal experience each would constitute an unusually elderly ticket, something that has received a lot of attention and criticism in recent elections.

The formula for determining the experience score is composed of two parts: combined federal government experience and combined non-federal government experience. Federal experience is weighted twice as much as non-federal experience (meaning it is weighted by 29.25 compared to non-federal experience’s weight of 14.625, so that a perfect score in both would result in the 43.875 that the total VPXP value is worth in the base score). The formula for both comes out to:

Where e is the mathematical constant multiplied by 29.25 in the first half for the federal experience weight; and by 14.625 for the non-federal experience weight, and federal experience is taken to the power of the candidate’s federal experience (fxp) plus vice presidential candidate’s federal experience (vpfxp) minus the mean squared, over the standard deviation times the sum of the candidate’s federal experience and the vice presidential candidate’s federal experience, all multiplied by negative one. Non-federal experience is to the power of the candidate’s non-federal experience (sxp) plus vice presidential candidate’s non-federal experience (vpsxp) minus half the federal mean (as we’re weighing it by half) squared, over half the federal standard deviation (once again, because we’re weighing it by half) times the sum of the candidate’s non-federal experience and the vice presidential candidate’s non-federal experience, all multiplied by negative one.

VPStateMargin: Last but not least is the VPStateMargin, weighted by 28.125% of the total base score.The reasons for this are discussed above in VPXP, but it boils down to complementary experience being valued by 1.56 times opting to pick a vice presidential candidate from a competitive state. If a VP candidate’s state margin, accounting for the generic ballot, is between -7.5 and 7.5, then the VPStateMargin is the square root of the vice presidential candidate’s state’s number of electoral votes over one plus the absolute value of their state margin. This is multiplied by the most competitive average electoral vote adjuster, which was determined by taking the total number of electoral votes (538) over the total number of states (51 including DC which has three electoral votes), which is 10.55, over a perfectly competitive state (assuming a state margin of 0), which is a value of 1. The square root of 10.55 is 3.248, which must be multiplied by 8.659 to equal the weight for this factor of 28.125. So 8.659 is the multiplier. This score gets higher if the state they are from has a large electoral vote count and has a very narrow margin. Yes, this technically does let it exceed 28.125 in cases where a state with a lot of electoral votes is going to be extraordinarily close, and indeed, if California (with 54 electoral votes) had no partisan lean, picking a vice presidential candidate from California would be a very smart thing to do, so this can overweight this factor if there is a clear electoral advantage to selecting a massive swing state.

If the VPStateMargin is not between -7.5 and 7.5, then the state is not considered competitive for the sake of this value, and it is simply calculated as the VP state’s electoral votes over one plus the absolute value of the state margin.

If you add these four factors together, you’ll have the base score. Multiply the coefficient by the base score to get the VP Score for a given nominee and VP nominee combination. If you choose a nominee it will run this function for every possible VP nominee:

We hope you enjoy the ensuing veepstakes as much as we do, please feel free to reach out to us with any questions or thoughts about this ongoing project and our research in this area. And if you’re a Republican presidential candidate or have a line to one, please pass our work along! We’ve spent a lot of time in the interest of fairness making sure the Republicans have the same tools available as the Democrats did in 2020 to select the strongest possible ticket going into the general election against the well-calculated Biden-Harris ticket next year. Better to rely on our free expertise and project buoyed by years of work in this area than a tacky website and public poll…