Is the Rust Belt Still the Lowest Hanging Fruit for Biden?

2012, 2016, 2020, and now 2024… “It’s the Rust Belt or bust” is the mantra of conventional political wisdom that just will not die out.

This idea survives because it has been, at least over the last few cycles, largely true. The tipping-point states – the closest states which delivered the pivotal 270th electoral vote – in the 2016 and 2020 elections were Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, respectively. It is nearly as hard to imagine how Barack Obama could have won in 2012 without carrying the region (though Colorado was the tipping point state in both 2008 and 2012). Indeed, the focus for any presidential campaign over at least 12 years has been the Rust Belt: a largely-Midwestern area including Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

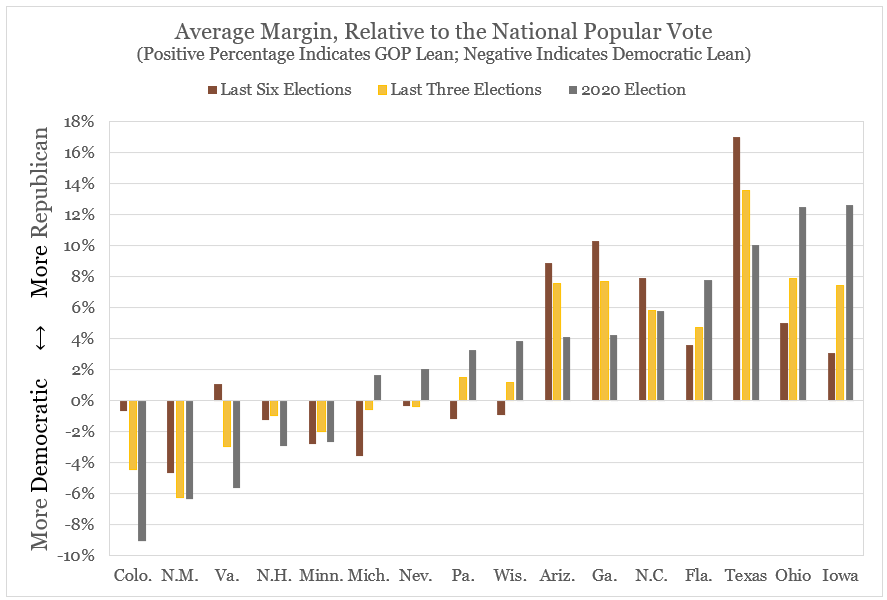

This region has been so important because its states have tight margins from an electoral standpoint. In the 21st century, 12 states have seen an average margin relative to the national popular vote equal less than 5%: all five of those aforementioned Rust Belt states are among them. If you look at only the last three presidential elections, all but Ohio retain their electoral relevance.

But, as this chart illustrates, the margins have moved decisively away from the Democratic Party in all five states. If the Rust Belt is moving away from Democrats, can it really be that the Rust Belt is still make or break for the party? Possibly. The conceit is that even as Democrats have lost ground there and made up ground elsewhere, the Rust Belt remains the lowest hanging fruit. It’s hard to imagine Democrats swinging Arizona or Georgia if they haven’t already won Michigan and Wisconsin.

The Crossover

But does this assumption actually carry any weight? You could fairly accuse us of being Sun Belt (home to Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, and Texas) apologists (or at least Midwest alarmists…), but you cannot accuse us of not being thorough. Particularly in the wake of the 2020 election, where Biden, despite a sizable national showing, barely managed to carry many of the Rust Belt states yet still managed to swing Arizona and Georgia, we struck a note which cautioned the Democratic Party’s reliance on the region. “2020 demonstrated the strength of the headwinds Democrats are up against in the Midwest but also proved that clinging to this past is unnecessary,” was the core of our argument, as we described a largely white, non-college educated region moving rapidly away from the party, while highlighting pickup opportunities which are as diverse as the Democratic coalition.

Our theory assessed electoral strategy with a long-term view: given existing trendline data and what we know about how these states have moved over the last few cycles, there will come a point in the near future where the trends eventually cross and it will become easier for Democrats to win Georgia (moving toward them) than Wisconsin (moving away from them). To describe it using the chart above: states whose bars are moving downward that used to clearly favor Republicans will – presumably – eventually be more Democratic than states whose bars are moving upward but who used to clearly favor Democrats. Ultimately, this will make the Sun Belt more electorally accessible to Democrats than the Rust Belt. For lack of a better term, let’s call this point the “crossover.”

There’s a lot of evidence to support this trend, which we will not rehash at great length given we spent a total of six articles exploring it a couple years ago, and there are some potential variables which might slow or even reverse the trend – like a migration of conservative voters out of the Midwest to states like Florida, or a disproportionate number of deaths among Republican voters due to COVID-19. But, given what we do know – margins in states across the last few presidential elections, the strength of the correlation in how they’ve shifted, and where the states were relative to the nation in the last election – we can assess where we stand in 2024.

What Is the Lowest Hanging Fruit in 2024?

Let’s start with a few constraints: going forward, we will only consider nine “crossover” states: Minnesota, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in the Rust Belt; and Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, and Texas in the Sun Belt.

In terms of each state’s starting point, here’s a pick-your-own adventure option: you can work from the 2020 election result (how many points to the left or right of the national popular vote a state was), but we’re pretty partial to using FiveThirtyEight’s partisan lean (which incorporates data from a couple more elections at varying weights). We’ll analyze the crossover based on both values for each of these states and additionally make one based on an average of these two values.

Finally, we need to continue to apply trendline data forward; we’ll do this similar to how our 2024 presidential election model works – by multiplying the average yearly shift of a state (based on a regression considering the last six presidential elections) by the R² (indicating the strength of the relationship between time and shift of a state) for that state. If we multiply this value by four and add it to whatever baseline we’re using, we’ll get the estimated 2024 lean.

As it stands, absent our nine crossover states, Democrats have 216 electoral votes and Republicans have 179. Let’s look at the year ahead.

In 2024, agnostic to the popular vote result, we would expect the state margins to look like this (leading party indicated by the color; italicized state indicates likely tipping point state which delivers the 270th electoral vote):

| State | Electoral Votes | 2020 Election Baseline | Partisan Lean Baseline | Average Baseline |

| Minnesota | 10 | 2.6% | 1.9% | 2.3% |

| Michigan | 15 | 2.5% | 2% | 2.3% |

| Nevada | 6 | 2.1% | 2.6% | 2.3% |

| North Carolina | 16 | 4.6% | 3.6% | 4.1% |

| Wisconsin | 10 | 4.1% | 4.1% | 4.1% |

| Georgia | 16 | 2.9% | 6.1% | 4.5% |

| Pennsylvania | 19 | 4.8% | 4.5% | 4.6% |

| Arizona | 11 | 4.1% | 7.1% | 5.6% |

| Texas | 40 | 8% | 10.9% | 9.4% |

If the popular vote is even, this is pretty bleak for Biden, who would lose every crossover state but Minnesota in a tight national election. If he carried the popular vote by closer to 2.5% (about the average in the last six elections), Nevada and Michigan are on the board, but he would still fall 23 electoral votes short.

All other things unaccounted for, this addresses our most pressing question: it’s hard to make out a path to a Biden victory this year without at least Michigan, even if he manages to swing Arizona, Georgia, and Nevada. Given what knowledge we have, the path to a Biden victory in 2024 runs in this order of ascending difficulty:

- Win Minnesota. This is very doable.

- Then win Michigan and Nevada. Biden is favored if he can eke out a popular vote victory on par with the average of the last six elections, even if he underperforms his 2020 margin.

- Then pick off at least two of Georgia, North Carolina, and Wisconsin. If Biden hits his 2020 margin, it would be tight, but he’d achieve this. The tipping point state, probably Wisconsin yet again, would be about 4.1% to the right of the nation.

That’s a tough break, as Biden has to essentially meet his 2020 national popular vote margin to overcome the map’s bias towards Republicans. It also suggests that at least two members of the Rust Belt are must-win lowest hanging fruit: Minnesota and Michigan. Of course, given Biden’s natural affinity and personal relationship with the state of Pennsylvania, there’s probably a strategic sense in fudging past these numbers and assuming Pennsylvania is easier to win than Wisconsin or North Carolina. Nonetheless, this still requires one of either Georgia, North Carolina, or Wisconsin.

This is a problem for Biden, in that the most achievable must-win states (like Michigan) and achievable must-win-one-of states (like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin) are moving away from his party faster and more consistently than budding alternatives in Arizona, Georgia, and North Carolina are moving towards his party. In a sense, this makes the 2024 election map harder for him, but he also has an incumbency advantage, so numerically speaking, it’s probably a wash compared to 2020.

It’s unlikely that either candidate has a path to the White House without winning several Rust Belt states in 2024. While Biden’s 2020 romp may have exposed what the demise of the Rust Belt’s electoral kingmaking will look like, his own electoral future is bound to the region for the time being.