South Carolina is Better at Picking the Nominee Than Other Early States

You’ve heard the news – the death of the first-in-the-nation Iowa caucus is upon us! Well, maybe. There’s at least some movement, as it looks like the Democratic Party is moving towards replacing Iowa with a more representative state like their new pick: South Carolina. Instead of hopping on the bandwagon of this being a fairness consideration (the national party, or any individual state, selecting the order of the states is inherently unfair – stay tuned for our proposal coming this holiday season!), we figured we’d launch into a slightly more interesting analysis on whether Iowa was is even any good at picking the winner, or if any of the other early states have done better.

Since 2008, we – with a couple aberrations, see the footnote – have been pretty acclimated to the four states that kick off primary season and their order.Florida made an aggressive push to go earlier in the calendar in 2012, so Nevada fell behind Florida in that year’s competitive Republican primaries because it refused to change its originally-scheduled date (while the other three all did). Michigan did something similar in 2008, entering the top four, and got in big trouble to the point where the DNC initially did not count the vote from Michigan as part of the primaries and their convention delegates had their voting power slashed in half. Iowa goes first, then New Hampshire, then Nevada, and then South Carolina. The first two are both about 90% white and among the most rural states in the nation; Nevada is the fifth-most urban and one of just six majority-minority states; and South Carolina has one of the highest shares of Black residents.

How did we get to these four? Well, without going into the history of the Iowa caucuses (whose prominence as “a thing” in politics we can largely credit to the political savvy of one Jimmy Carter), the loose history is that New Hampshire has had the first primary since the mid-20th century. Iowa’s prominence emerged after the Democratic Party’s reforms following the tumultuous 1968 Democratic National Convention. Nevada leapt ahead in 2008 thanks to the machinations of then-Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid and South Carolina also moved up in 2008 in order to preserve its status as the first-in-the-South primary. The convenience of having one state from each region of the country in the first four was great and the fact that Nevada and South Carolina have more diverse and fewer rural voters clearly played a factor in keeping them in the lineup, and that all sort of loosely explains why we got these four and have not budged much since.

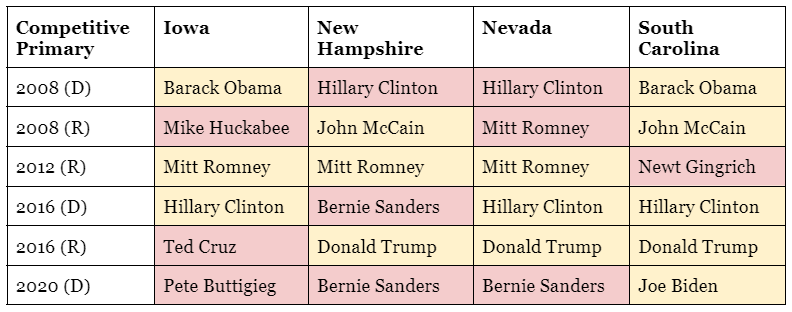

But how effective have they been in actually selecting the ultimate presidential nominee? Across both Democrats and Republicans, Iowa’s lost its predictive luster. Though it correctly picked the Democratic nominee in every competitive (excluding incumbent presidents) primary from 2000-2016, it lost its streak in 2020, and it hasn’t successfully picked the Republican nominee out of a competitive primary since George W. Bush in 2000.

Is New Hampshire any better? Of the six competitive primaries held since 2008, it failed to pick the Democratic nominee every single time – but went three for three on Republicans. Nevada’s record is also mixed, only three-for-six overall, better at calling Republicans than it is Democrats.

Which leaves South Carolina… which only dropped the ball once. Barring its support for Newt Gingrich (who, being from neighboring Georgia, relied heavily on the Palmetto State’s primary in 2012 – the proto-Joe Biden), it has correctly called the party’s final nominee every other cycle.

This makes it the only state to call every Democratic nominee correctly (New Hampshire has this distinction for Republicans), and – as the primary state he owes the most for his nomination – the kingmaker of its current president. But is this record a little overstated?

One caveat is that South Carolina has – in all these years but 2008 – gone last. Due to the sheer number of dropouts after Iowa and New Hampshire, this leaves it in a stronger position to know who is a stronger candidate and how the race is shaping up. It also means the field is winnowed down to a few survivors, among whom one must be the eventual nominee. It’s a bit of a false equivalency in this way, because South Carolina has far more information than Iowa had, significantly more than New Hampshire had, and a little more than Nevada had as to how candidates are doing and who to vote for. However, in the neck-and-neck Democratic primary of 2008 between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, South Carolina still selected the winner. And, more astonishing, in 2020 – despite the fact Joe Biden got fourth place in Iowa, then fifth place in New Hampshire – South Carolina gave him nearly 50% of the vote and first place in their primary, pulling both the winner and the next president from the depths of the prior primaries.

Though going fourth certainly gives them an advantage in a smaller field (you have a better chance of picking the March Madness champion from the Elite Eight than from the Round of 64), it’s worth noting that because they have an electorate that looks more like the Democratic Party overall, they probably tend to pick a candidate that more generally appeals to Democratic voters nationally, especially compared to disproportionately-white non-college-educated electorates in Iowa and New Hampshire. While it may not be fair for South Carolina to be directly picked to go first (and there are undeniably many states – including Nevada – who better reflect the Democratic electorate overall), South Carolina’s superior record and diverse electorate makes it a much better pick to go first than Iowa or New Hampshire.

Still think it’s not fair? Stay tuned! This holiday season, in a mix up from some regular programming, we’ll be issuing our own proposal for how to improve the presidential primary system in the United States!