The Midwestern Reality: Iowa and Ohio, Bellwethers No More

This is the second piece in our series of six features on the Midwestern Democratic decline where we’ll be diving into consequential parts of the Midwest and the prevailing headwinds faced by the Democratic Party in the region. We’ll use each part to build on a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted relative to the nation at large, and demonstrate how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.

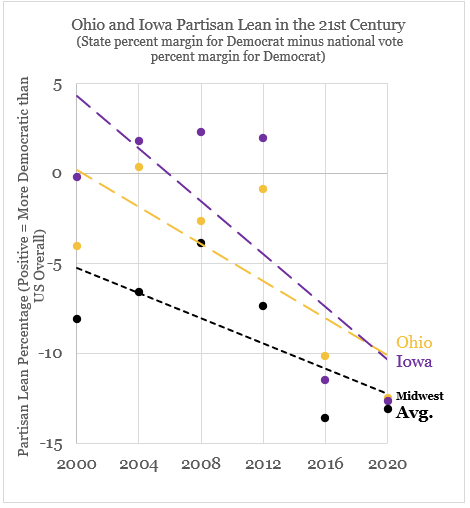

For 60 years, as went Ohio, so went the nation. Not since 1960, in which Nixon won Ohio but Kennedy won the presidency, had Ohio gone for the losing presidential candidate. Obama won Ohio by almost 5% in 2008, and by just under 3% in 2012 when it was considered the critical state to win. Always leaning ever-so-slightly Republican, something changed dramatically after the Obama years. Trump beat Clinton there by over 8% in 2016, a dramatic swing in an election that the Democrat still carried by 2.1% nationally. And then Trump beat Biden there in 2020 by 8%, while Biden carried the nation by 4.5%. Ohio had become more conservative, and fast.

So fast in fact, that the Trump and Biden campaigns only spent a combined $19 million there in 2020, and made a total of 13 campaign stops. In 2016, the candidates made 48 stops total and spent over $28 million in the state. The drop off in campaign stops can be partially attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, but a drop of nearly a third in ad spending? It was because the state was no longer a bellwether at all. “I think the Biden campaign sees other states as more important, and the Trump campaign has to assume a victory in Ohio because if they lose it, they have no chance anyway,” noted Kyle Kondik of the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. Biden didn’t need Ohio to win. Clinton wouldn’t have either had she carried a few of the states where her margin was closer. Even in 2012, Obama didn’t need the “critical” Ohio or any of the states that were more competitive than it, so long as he carried Colorado and every state he won by a larger margin (almost 5.5%), he would have been just fine.

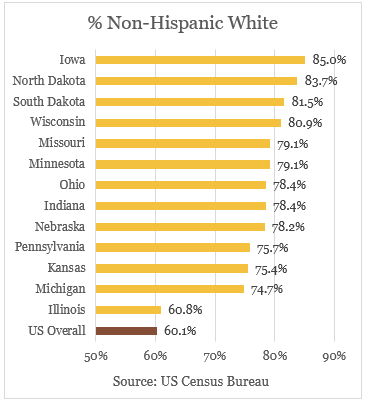

In reality, Ohio’s bellwether status has always been more of a historical fluke than a reflection of the makeup of the country overall. The United States is about 60% non-Hispanic white, but Ohio is 78.4% non-Hispanic white. Though every single Midwestern state is whiter than the nation as a whole, it is telling that the only one that is less than 70% non-Hispanic white is Illinois, the most Democratic-leaning of the Midwestern states.

At the opposite end of the Midwest from Illinois is Iowa, a state that is 85% non-Hispanic white. After voting for Barack Obama twice, by 9.5% in 2008 and 5.8% in 2012, it went for Trump by 9.4%, an extraordinary shift to the right — more than every state but West Virginia and North Dakota. Having a less diverse electorate matters; contrary to the pervasive post-2016 narrative, racial resentment drove Trump voters more than any kind of economic anxiety. The Midwest as a whole rates terribly in terms of racial integration, with Iowa and Wisconsin performing the worst. But while neighboring Illinois and Wisconsin are buffeted by the larger metropolitan areas of Chicago and Milwaukee (which are, admittedly, two of the three most segregated major cities in the country), Iowa’s largest city, Des Moines, does not even crack the largest 100 cities in the United States. Instead, Iowa is one of the most rural states in the nation.

As Iowa and Ohio’s racial makeups have diverged from the national average in this century, it has become apparent in their politics as well. The situation is more dramatic in Iowa, which was a Democratic-leaning state from 2004-2012, but has moved to the right faster than any other Midwestern state besides Missouri. Ohio’s decline is faster than the Midwest’s average as well but the fact that it has changed so dramatically despite its sheer size advantage is concerning for Democrats. Logically speaking, smaller states should have more dramatic changes than large ones because when a minority of people change their minds or move in or out of the state, it’ll have a larger impact on a state with a smaller population. But Ohio’s transition from bellwether to a relatively safe state for Republicans in less than a decade is striking given it has more than 3.5 times the population as Iowa.

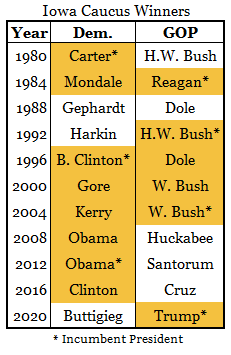

Disproportionately white and rural Iowa was a bellwether in a different way from Ohio. Since 1972, Iowa has held the first in the nation caucus for presidential nominations. A victory in the Iowa caucuses was a surefire springboard to national attention and often the nomination for prospective presidential candidates. At least, for a little while. Over the last four decades, it went from a winning streak to near irrelevance. Over the last 11 cycles, there have been 22 Iowa caucus winners. It has correctly called the winner in 14 cases, performing especially well from the mid-90s through the 2000s. However, if you strip out the seven incumbent presidents (who were all renominated as a formality), the Iowa caucuses have only called the eventual nominee correctly in seven of 15 cases over the last four decades. The caucuses have failed to select the eventual Republican nominee in the last three open races, and broke their two-decade-long streak correctly selecting the eventual Democratic nominee in 2020.

The fact of the matter is that the Iowa caucuses aren’t particularly representative of the Democratic Party at large. Demographically, Iowa looks the least like the Democratic Party than all but nine states, and there are a number of viable alternatives for more representative first nominating contests we’ve profiled before. There’s been some momentum both vocally and in substance to select a more reflective state, but even after the disastrous 2020 Iowa caucuses, which were plagued by disorganization and technical problems, it’s not clear that Iowa’s first in the nation status is going anywhere soon. But practically speaking, Biden’s eventual nomination may have weakened Iowa’s status even if it maintains its primacy. Iowa no longer has the predictive power it did for Democrats, especially as Democrats have become a more metropolitan, less white, and more educated party.

What’s unusual is Iowa’s inadequacies at selecting the eventual Republican nominee. Republican primary voters are about 86% white, almost exactly the same percentage as Iowa. But over the last three non-incumbent cycles, the Iowa caucuses selected a candidate that was perceived as more conservative than the eventual nominee: voters who identified as “very conservative” preferred Mike Huckabee over McCain in 2008; they backed “conservative warrior” Rick Santorum over the more pragmatic Romney in 2012;Albeit by only 34 votes, the closest margin in the Iowa caucuses’ history. and selected the “hard-right crusader” Ted Cruz over the ambiguous and ideologically flexible Trump in 2016.

This is probably attributable to the way Republicans choose their nominee, using more winner-take-all primaries to award delegates later in the primary season while allocating votes proportional in early states like Iowa. Of the last three open field nomination cycles for Republicans, only Romney has won a majority of votes in the Republican primaries (52.1%). Trump and McCain were both plurality winners in the overall field winning 44.9% and 46.7% respectively, with their three runners up winning more votes than they did overall. This is far more unlikely in Democratic primaries which are designed to guide towards a consensus candidate as opposed to a factional one. In the 21st century, only Obama in 2008 failed to win an outright majority of votes in a Democratic primary without an incumbent running.

That these two prior bellwether states fail to represent the United States to the tune they once did has become obvious in the last decade. Racial diversity aside, both states are older, less educated, and have a lower income per household than the United States at large. Though Ohio is not significantly less urban than the nation overall, Iowa is dramatically so; along with its overwhelming size, this may go a long way towards explaining why Ohio’s rapid decline in Democratic partisan lean has been slightly less pronounced.

After their pronounced shift to the right, both Iowa and Ohio are now more Republican leaning than Arizona, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas. That’s a far cry from Iowa’s reputation as a microcosm of small town America that prospective presidents of both parties would pay heed to in order to curry favor with rural voters. And the must-win Ohio of the early 21st century has stagnated to near-irrelevance in the national election. Instead, Iowa has supplemented its primary kingmaking prowess with “Make America Great Again” platitudes and Ohio has lost its streak tracking with the national victor in a span not of decades, but years. Democrats’ continued focus on these states at the expense of others is a dangerous risk that carries little reward. These are states they do not need to win, whether they’re willing to admit it or not.