The Midwestern Reality: Kansas and Nebraska, Suburban Saviors

This is the fifth piece in our series of six features on the Midwestern Democratic decline where we’ll be diving into consequential parts of the Midwest and the prevailing headwinds faced by the Democratic Party in the region. We’ll use each part to build on a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted relative to the nation at large, and demonstrate how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.

Driving east from Denver on I-70, Colorado turns into the Great Plains faster than you can sing “Rocky Mountain High.” As the Front Range megaregion surrenders to broad fields, a long, quiet drive begins. The office parks and suburbs of Aurora, Colorado give way to rustic, handmade “ADOPTION NOT ABORTION” billboards installed on farmland on each side of the highway. Save for a dramatic reduction in gasoline prices and a small group of people coming the opposite direction at the “Welcome to Colorful Colorado” sign (there never seem to be any folks taking photos at “Kansas Welcomes You”…), it’s hardly noticeable that you’ve crossed into the Sunflower State. Anti-abortion signs (“THANK MOM FOR CHOOSING LIFE”) continue to adorn the highway, and Wheat Jesus beckons you to Colby, Kansas — “the oasis on the plains,” as its fake palm trees go out of their way to emphasize. Quintessential roadside attractions dot parts of the highway as you make your way east: the Garden of Eden, the “World’s Largest Easel,” the “World’s Largest Hand-Painted Czech Egg,” dilapidated porn stores, deserted gas stations, and corn and wheat growing as far as the eye can see.

Until that too relents. I-70 curves through Topeka and around Lawrence, two lanes give way to three, three to four, and at the junction of the Kansas and Missouri rivers looms the “Paris of the Plains,” the City of Fountains: Kansas City. A metropolitan area straddling the Kansas and Missouri state lines, with a burgeoning brewery scene, a deep musical tradition, some of the most famous barbecue in the world, and a large federal workforce. Diverse urban- and suburbanites gather in the largest city within 500 miles. In a hip neighborhood adjacent to the Missouri River in downtown Kansas City, the City Market boasts a daily farmers market with a crowd not dissimilar from what you’d find in cities as disparate as Denver or Washington. Free wifi covers core parts of the city and an unexpectedly prolific arts scene further elevates a city underestimated by its coastal equivalents.

North on I-29 from Kansas City lies Omaha, Nebraska’s largest city, and one with a similar role to play in this tapestry of the Midwest. An unsuspectingly wealthy city, Omaha is home to companies such as Berkshire Hathaway, Kiewet Corporation, Mutual of Omaha, and Union Pacific Railroad. The city’s large industries such as telecommunications, IT, and financial services come together with its other large industries, meatpacking and agriculture, serving as a bridge between blue collar and white collar jobs. But Omaha and Kansas City, as large cities on the plains, share a secret in their suburbs that differentiate them from mid-sized contemporaries on the other side of the Missouri such as Des Moines, Sioux Falls, and Fargo.

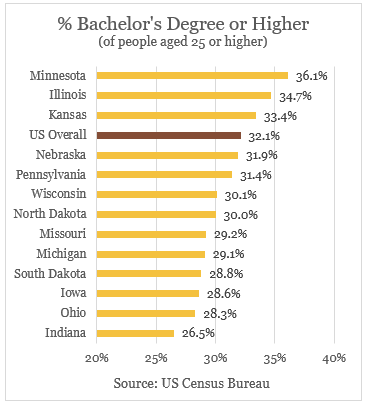

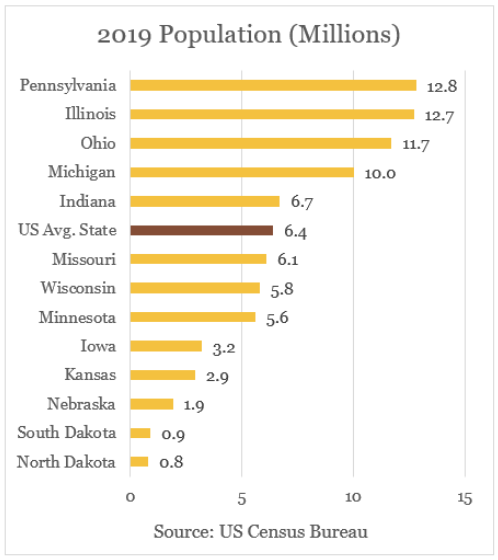

Most of Kansas City sits on the Missouri side, but since 2000 all of the metro area’s job growth has actually occurred on the Kansas side — over 40,000 jobs added in Kansas while over 20,000 were lost on the Missouri side. Missouri is the larger state, population wise, and has grown slower overall, but there are stark differences in the demographics of these two states across which Kansas City sits that portend dramatically different political destinies. Much of Kansas is rural and white, sure, but what is often neglected is that Kansas is one of only three Midwestern states that is more educated than the national average.

This is huge; even among white voters — traditionally a Republican mainstay — educated and professional class voters have moved in the Democratic direction, especially in the wake of Trump’s 2016 nomination. This “educational rift” is a significant change in American’s voting behavior. Republicans won those with only a bachelor’s degree in every election since 1988 (the first year data was available) other than 2008 (these voters still leaned Republican in this election though, as Obama won them by 2% in 2008 but won the election by around 7.3% nationally), until 2016… In 2012, 53% of college-educated voters (ignoring postgraduates) voted for Romney over Obama, but in 2016, Hillary Clinton won college-educated voters, and in 2020 Biden won these voters by 4%. For those with a postgraduate education, Democrats performed even better. Trump became the first Republican presidential candidate in 60 years not to win white college graduates.

Education level is now one of the most significant predictors of electoral behavior, behind only religion, race, and sexual orientation. And there’s even more good news for Democrats: the more educated the voters, the more likely they are to vote. It’s even been suggested that this may undermine Republican’s own attempts to make voting more difficult in the wake of the 2020 election, the great irony being that absentee ballots and other accommodations aided less educated, rural, and older voters — all of whom lean Republican — while the now-Democratic-leaning educated voters often vote at a high propensity and can more handily navigate voting challenges.

Kansas overperforming the Midwest’s education levels is most reflected in its suburbs. Kansas City suburbs like those found in Johnson and Douglas counties and highly educated counties like Riley County (which contains Kansas State University) all moved left in 2016. This suburban shift in particular is essential to Democratic prospects, as rural voters have abandoned the party in droves and the ancient version of the suburbs no longer exists. Suburbs are now more diverse and more educated than their outdated archetype suggests; they vote and look more like reliably-Democratic urban areas. Kansas and Nebraska both are among the smallest Midwestern states, so their suburban and urban centers hold far more sway than those of their larger neighbors. At the congressional district level, Biden won Kansas’ 3rd congressional district, which covers Overland Park and much of Johnson County in the suburbs of Kansas City, by over 10%, while Clinton carried it by less than 2% four years prior, and Obama lost it by almost 10% four years before that. More clearly (because it awards electoral votes based on congressional districts, the only state to do so other than Maine), Biden won Nebraska’s 2nd congressional district, home to Omaha, by almost 7% — a speck of blue among the red plains, even as Trump barely carried it in 2016 and Romney carried it by 7% in 2012.

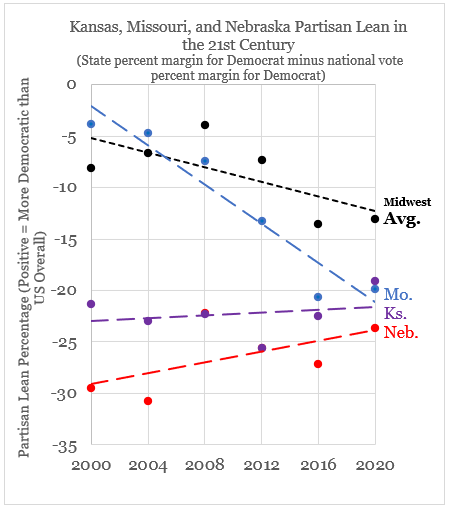

Kansas City and Omaha’s urban and suburban areas, which are surrounded by some of the most Republican parts of the country, illuminate the most surprising trend in both Kansas and Nebraska relative to the rest of the Midwest. Other than deep blue Illinois, they’re the only two Midwestern states getting bluer. As the Midwest overall has become more Republican at an average rate of 0.35% per year, Kansas has become more Democratic at 0.06% per year and Nebraska at 0.26% per year. The change is more evident in Nebraska, which came from leaning about 30% more Republican than the nation as a whole to about 24% as of 2020; Kansas started less Republican-leaning (around 22%) and was about 19% more Republican than the nation as a whole as of 2020. This has resulted in a convergence across the eponymous river as Missouri, with a population larger than Kansas and Nebraska combined, has become more Republican-leaning at a rate of 0.95% per year — faster than any state in the Midwest. A far cry from 2008, when the Show-Me State was the closest state in the election; Obama lost it by fewer than 4,000 votes.

Don Bacon, a Republican who represents the Nebraska congressional district that Biden ultimately won, warned before the 2020 election, “We’re also Nebraska nice… and we want more diplomacy and decency, and I think that’s what hurts the president.” Biden went all in on the district, spending six times what Trump did there — all for one electoral vote, mind you. Republican Bacon won on the same ballot as Democratic Biden, one of only nine districts to elect a Republican to Congress but also vote for Joe Biden, and the only one in the Midwest.Pennsylvania’s 1st congressional district is one too, but it borders Philadelphia so — per our last article — it’s probably not fair to call that district “the Midwest.” In a New York Times/Siena College poll before the election, Trump was down 7 points against Biden in the district, but Bacon was ahead by 2 points against his Democratic challenger — because he performed better with women and independent voters. As Politico reported, “The upshot was that Omaha and its suburbs were not breaking against Republicans. They were breaking singularly against Trump.” As the Republican Party has embraced Trumpism and election falsehoods, even after Trump’s loss, this portends well for Democrats. Tellingly, Bacon was one of only 37 Republican members of Congress to acknowledge Biden as the president-elect in December of 2020, did not vote against the certification of electors, and was one of 35 Republicans who voted in favor of a bill establishing the January 6 commission before the Senate failed to clear the bill.

But it is Kansas that provides the more interesting tail end to this story of the Midwest’s unlikely liberal enclaves. Its slow march away from its deeply conservative starting point in the 21st century is a subtle about-face from Kansas’ well-chronicled conservative history, which is in turn a dramatic about-face from its progressive entry into the United States to begin with. Thomas Frank’s 2004 book What’s the Matter with Kansas? chronicles Kansas’ journey from violent conflict over whether the state would be a slave state or free state in the 19th century to the center of the progressive movement in the early 20th century before becoming a bastion of conservatism in the late 20th century. Frank describes the culture wars — abortion, gay marriage, and the like — as a method for channeling voters against a coastal and liberal elite (who Frank, despite being from Kansas, is somewhat self-admitting of being himself) who think they’re better than middle America, while Republicans embraced a form of free market capitalism that only benefited the rich in the state. In his mind, these conservatives really fall into two camps: “Cons” and “Mods.” The Mods (pro-business Republicans who don’t really care about culture war issues) take advantage and stoke the passions of the “Cons” (culture war conservatives obsessed with stopping abortions and gay marriage) in order to elect Republicans to hurt these very people by embracing capitalist policies. To add insult to injury, in Frank’s mind, Democrats embraced this: the party’s leaders such as Bill Clinton and Al Gore espoused this pro-trade, pro-business mindset, eschewing blue collar issues that formed the backbone of the party’s 20th century history.

Frank’s chronology is effective and compelling, and prescient given what we’d see in the two decades since the book’s publication. “Trump… sounded like he’d been convinced to run for president after reading What’s the Matter with Kansas? His stump act seemed tailored to take advantage of the gigantic market opportunity Democrats had created, and which Frank described. He ranted about immigrants, women, the disabled, and other groups, sure, but also about NAFTA, NATO, the TPP, big Pharma, military contracting…” noted a 2020 reminiscence on Frank’s work. But Frank’s thesis also missteps early on: it castigates Johnson County, “a metropolis built entirely according to the developer’s plan,” a “suburban empire.” “One of the most intensely Republican places in the nation,” wrote Frank in 2004, noting that “of Johnson County’s twenty-two representatives in the Kansas house, only one is a Democrat.” In 2021, of Johnson County’s 25 representatives in the Kansas house, a majority are now Democrats. Kansas’ 3rd congressional district, in which Johnson County resides, was won by Romney in 2012 before being won by Clinton in 2016 and Biden in 2020. It’s congresswoman, Sharice Davids, unseated the Republican incumbent in 2018 by a 9% margin and won reelection in 2020 by 10%. This puts her in line with other Democratic suburban overperformers that came into office in the Trump era like Colorado’s Jason Crow and New Jersey’s Mikie Sherrill. Unlike Colorado or New Jersey’s overperformers, but especially notable given she comes from Kansas, Davids is the first openly LGBT Native American elected to Congress. She is almost literally the polar opposite of what you might expect if you read Frank’s seminal work a decade ago and filed Johnson County away as “cantankerous and troublesome” as his book does.

Kansas has always been slightly more moderate than its detractors allege — it has not elected two governors from the same party in a row since the 1960s, and its last three Democratic governors have also all been women. Only Arizona has had more women as governors than Kansas — while Democratic-leaning states like California, Colorado, New York, and Maryland have never once elected a female governor.In the Midwest, Iowa, Nebraska, Ohio, and South Dakota have all elected one female governor, all Republicans. Michigan has elected two, both Democrats. New York has never elected a woman as a governor but, with the resignation of Andrew Cuomo in 2021, Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul became governor. The state has produced some of the most powerful (and some of the most disgraced) people in the modern conservative movement — for every Mike Pompeo or Bob Dole there is a Kris Kobach or Sam Brownback — but these are two sides of a coin in conflict with itself, pushing voters to scramble to elect a moderate Democrat in their stead. The Trump-Pence ticket only won 56% of the vote in Kansas in both 2016 and 2020. In 2020, Kansas was among the 20 closest states in the election, the first time since 1916 it voted more Democratic than Missouri.

Nationally, Republicans bested Democrats electorally by getting ahead of the demographic curve in places like Michigan, Iowa, and Ohio, and catering their message to those voters. Democrats need to stop stalling the inevitable by playing defense and look to where they’ll appeal in the next decade rather than the last. Kansas and Nebraska may be outliers in the Midwest, but they are already whispering the answer, and offer the best lessons as to where the party must go. In 2020, the diverse metropolitan center of Omaha handed Joe Biden one of the nation’s most unusual electoral votes in a stinging rebuke of an incumbent president. Biden was the first Democrat in over 100 years to carry Johnson County and the first Democrat in history to carry Riley County.

If Democrats ignore the reasons why they’ve quietly performed better in America’s urban and suburban heartland, they risk not just losing elections, but losing their base of high-propensity, educated, diverse, and pragmatic voters in places they didn’t even realize they stood a chance.