The Midwestern Reality: Michigan and Minnesota, Fast and Slow Decline

This is the third piece in our series of six features on the Midwestern Democratic decline where we’ll be diving into consequential parts of the Midwest and the prevailing headwinds faced by the Democratic Party in the region. We’ll use each part to build on a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted relative to the nation at large, and demonstrate how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.

“Snatch and grab, man. Grab the fuckin’ Governor. Just grab the bitch. Because at that point, we do that, dude — it’s over,” is how Adam Fox, now indicted for conspiracy to commit kidnapping, described the plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer in 2020.

Members of the kidnapping plot tied to a Michigan militia group called the Wolverine Watchmen spent months training to storm the state capitol in Lansing, with the aim of taking hostages and trying the governor for “treason.” Perhaps too messy an undertaking, they constructed explosives and reportedly planned to blow up a bridge as a distraction while they kidnapped the governor from her summer home, so that they could transport her to Wisconsin for her “trial.”

Nowadays, these militia groups are evolving, changing, and less formal, all fostered by online activity. With a president providing implicit permission to oppose the “deep state” and threatening “civil war,” Governor Whitmer’s COVID-19 lockdowns fit firmly into the narrative of anti-government militants. “Suddenly, people were at home all day, feeling anxious and fearful about the future and spending a lot more time online. Many in the militia movement chafed at state lockdown orders, and started appearing, heavily armed, at state capitols across the country to protest what they saw as an assault on their individual freedoms,” FiveThirtyEight writers Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux and Maggie Koerth explained in their piece on the modern militia movement.

Militia movements and militia mentality have increased dramatically over the last two decades, predominantly following the 2008 election of Barack Obama. But the Midwest in general and Michigan in particular became a hotbed of militia activity unlike any other in the nation, with deadly consequences. The plot against Whitmer came on the heels of protests in Kenosha, Wisconsin following the police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man with his children in the car. The National Guard were deployed to Kenosha as several days of protest and riots engulfed the city. During the unrest, 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse fatally shot two protesters, embodying the self-styled vigilante embraced by the militia mindset. Fox News’ Tucker Carlson intoned, “How shocked are we that 17-year-olds with rifles decided they had to maintain order when no one else would?” Right-wing media embraced the footage of violence over protest, called “riot porn,” further accommodating the fantasy of citizens “taking justice into their own hands.”

Though these two examples are tragic and have been condemned by many Republicans, look no further than the 2020 Republican National Convention to see how this mindset has been embraced by the Republican Party at large. After Mark and Patricia McCloskey brandished firearms at protesters in St. Louis, they were invited to speak at the RNC where they proclaimed their victimhood after being charged for this show of force. Mark McCloskey is now running for the Senate seat being vacated by retiring Roy Blunt in Missouri, noting “God came knocking on my door last summer disguised as an angry mob, and it really did wake me up.”

The embrace of this mentality has consequences. “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!” is what then-President Trump tweeted in April of 2020, before the Whitmer kidnapping plot materialized. These words had meaning, apocalyptic language calling for a restoration of liberty begets dramatic action — how else should people be expected to behave when they believe their life and liberty is under siege but with armed rebuke? But this dog whistle paints only part of the story, and allows the president to be a scapegoat for a deadly reality.

Michigan’s history with militia movements begins long before Trump and Obama. It’s where Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols plotted the Oklahoma City bombing, and where the Hutaree militia were arrested as they conspired to “levy war against the United States.” Federal government response to the Ruby Ridge standoff in Idaho in 1992 and the siege in Waco, Texas in 1993 gave publicity to these anti-government sentiments nationally, but the movement moved further underground after the Oklahoma City bombing. Former Michigan-based FBI agent Andrew Arena questioned this persistence, “We had representatives of every known right-wing, white supremacist, anti-government group out there. And why Michigan, we just could never tell.”

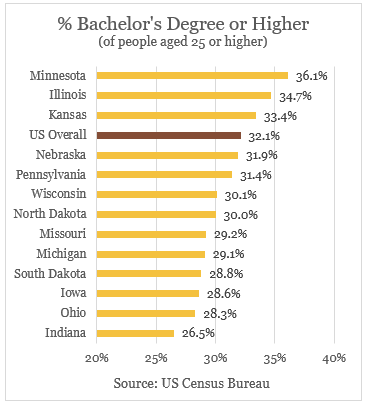

Urban decline has encumbered Michigan for decades, Detroit is the most famous case, but dramatic stories of urban blight such as in Flint or Saginaw, or cities with persistent population decline like Dearborn, are prevalent in the state too. Michigan, like fellow Midwestern states Iowa, Indiana, and Wisconsin, contains a large share of blue-collar workers. In part a result of poor employment prospects and urban decline, Michigan has grown slower than the rest of the country. Its proportion of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher is 3% less than the US overall and it is under 75% non-Hispanic white, more diverse than the rest of the Midwest except Illinois, but with a larger white population than the national average of 60%.

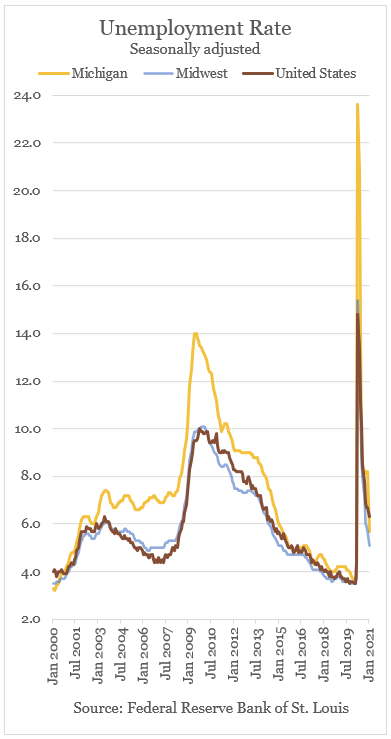

But the decline of manufacturing in the state has coincided with a level of unemployment that has tracked above the national average, and the Midwest region in general, for almost all of the 21st century, most dramatically over the course of the mid-2000s through the Great Recession and again during the COVID-19 recession.

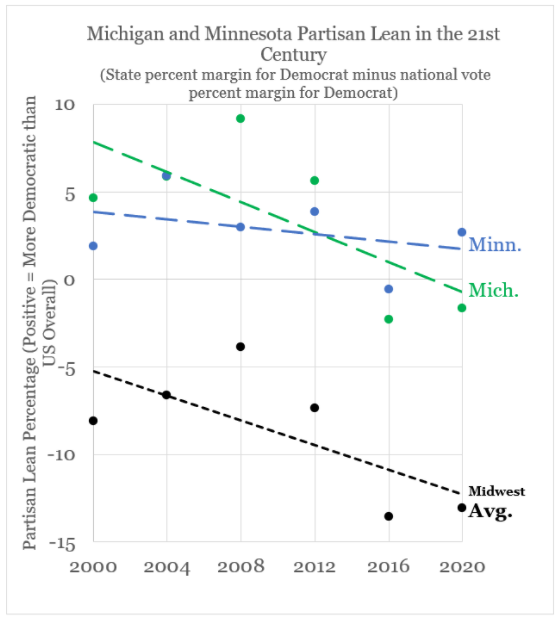

Over this same period, Michigan has moved from a reliably Democratic-leaning state to ever-so-slightly leaning Republican. After a 16.4% margin for Obama in 2008 (9.17% more Democratic than the nation overall), and a 9.5% margin for him the following cycle (5.6% more than the nation overall), Michigan veered into Republican territory. Trump won Michigan by the narrowest margin of any state in 2016, by 0.23%, and then Biden won Michigan by less than he won the national popular vote by, solidifying a more permanent Republican lean than expected. Gretchen Whitmer’s election by a 9.5% margin in the 2018 midterms provided some glimpse of hope, but an unusually narrow 2020 Senate election in which Democrat Gary Peters won reelection over Republican John James by less than 2% was concerning for Democrats as it was the most competitive Senate race in the state since 2000.

Across Lake Superior, another mid-sized Midwestern state looms, which has taken a different path. The state with the longest streak voting for the Democratic presidential candidate (since 1972, in fact — which means that it was the only state not to vote for Reagan’s reelection in 1984) shocked the political world when Trump came within 1.5% of winning the state in 2016. After the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis in 2020 rocked the city and the state for months, Republican appeals for law and order were often explicitly directed at the state. The Minneapolis unrest turned into the most destructive riots experienced by a city since the Los Angeles riots in 1992 following the acquittal of officers charged with excessive force against Rodney King. Minnesota received more visits by the presidential and vice presidential candidates than Georgia, New Hampshire, or Iowa. It received more spending on campaign ads than Iowa or Ohio too, roughly on par with Nevada and Georgia. But Biden won the state by 7.1% compared to Hillary’s 1.5% four years earlier. So what happened?

For one, Biden’s national margin was better. If we look at Minnesota’s Democratic margin relative to their national margin over the last six cycles, we can see that Minnesota has rarely deviated from about a 6-point spread centered around 2.8% more Democratic leaning than the nation as a whole. Over the last two decades nonetheless, Minnesota’s vote for the Democratic candidate relative to the Democratic vote nationally has slowly narrowed. Minnesota did not prove to be too competitive in 2020, despite the Trump camp’s aggressive play for the state, largely because Biden’s national performance was better. This papered over the fact that it was still, relative to their national vote, the second-worst performance in Minnesota by the Democratic candidate since 2000.

There are a couple prominent features about Minnesota that have flattened this trend. In Democrats’ favor is Minnesota’s high proportion of college-educated citizens. Minnesota scores as the tenth most educated state in the union based on this measure, outpacing the rest of the Midwestern states. As educational attainment has become a stronger predictor in Democratic vote share — especially in the last two cycles — this contrast holds a major clue as to why Minnesota’s margin has tightened slower than much of its Midwestern counterparts. If you recall Iowa and Ohio’s steep turn towards Republican-leaning states, this key distinction in education is of particular note; they both score in the bottom three states in terms of bachelor’s degree attainment in the Midwest, ahead of only Indiana.

The Twin Cities metro area also dominates Minnesota more than other prominent Midwestern urban areas dominate their states. Biden’s vote totals in Hennepin County (home to Minneapolis) and Ramsey County (home to Saint Paul) combined equaled about 43% of his total votes in the state. This is similar to a state like Illinois, where Biden’s vote totals in just Cook County (home to Chicago) equaled half of his total votes in the entire state.Cook County alone accounts for over 2% of Biden’s votes nationally. Keep in mind this is an area of land smaller than Rhode Island. But it contrasts starkly with states like Michigan, where Biden’s votes in Wayne County (home to Detroit) accounted for just 21% of his votes in the state; Wisconsin, where Biden’s votes in Milwaukee County accounted for just 19% of his votes in the state; and even — if you wanted to be incredibly generous — Ohio, where Biden’s combined votes from the counties of Franklin (Columbus), Hamilton (Cincinnati), and Cuyahoga (Cleveland) accounted for only 40% of his total votes received in the state. Minnesota’s vote share is simply so much more concentrated in its major metropolitan area that dilution in rural areas has been less pervasive, and this is a reinforcing feature too as those in your neighborhood and in your social circles can have an influence on your own voting preferences.

This urban power also matters in regards to the issues regarding race that broke out both nationally and in the Midwest specifically. Racial resentment across the Midwest and the exploitation of this pressure by the Republican Party put a target on Minnesota in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020. As the state where the murder took place, backlash to the protests could have primed Republican voters. But it also could have encouraged Democratic voters in the urban and suburban areas into what was ultimately a wash: not quite as Democratic leaning as the state usually is, but a slight recovery from its 2016 performance. The surge of grassroots political activity in the form of protests and registration resulting from Floyd’s murder no doubt contributed to the highest levels of voter turnout since 1900, but it’s unclear that this message will resonate permanently. It’s also apparent that there has been some degree of backlash to defund the police messaging, if not electorally yet, then certainly in rhetoric. Democratic candidates are not embracing that message as emphatically and many of them, including President Biden, are running from it entirely.

Outside of the Twin Cities, the decline in Democratic electoral performance is very apparent. Minnesota’s share of non-Hispanic whites without a bachelor’s degree have a progressive history and it remains the Midwestern state with the highest share of union members, 15.8% of all employed workers as of 2020. But states that rapidly became more Republican-leaning over this same period like Michigan and Ohio also have above-average union membership, so it’s not evident that this is curtailing this transition.

Instead, places like Minnesota’s Iron Range, home to a large unionized mining workforce, have turned away from the Democratic Party — or, technically, in Minnesota, the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, founded in 1944 as a merger between the two parties. A region known to vote for Democrats by 60% or more now narrowly broke for Clinton in 2016 and Biden in 2020. It is represented by a Republican Congressman, Pete Stauber — who won his seat in 2018, marking one of only three Republican House seat pick ups in the 2018 midterm.One of the other two pickups was also in Minnesota in its first district, at the southern border of the state. The other was in Pennsylvania, partially a result of forced redistricting. This is notable for the fact that since 1947, the district has only been represented by a Republican for four years total, including the last two by Stauber. Trump’s influence on the Republican Party accelerated this shift, as former Democrats become increasingly alienated by their former party. Trump’s rhetoric on migrants, especially on Somali refugees who have a large population in Minnesota, hit home in the state and the Midwest in general. His policy on tariffs and antipathy to international competition has also been embraced by many in rural Minnesota.

This ultimately equates to all but a tiny portion of the state becoming more Republican while the Twin Cities and their suburbs have counterbalanced this shift by becoming more Democratic. Minnesota may have been more resistant to the demographic headwinds plaguing the Democratic Party in most of the Midwest, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for Democrats to hold without winning a substantial national margin. Its reign as the longest-voting Democratic state seems primed to end in the near future, likely as soon as the Republican candidate next carries the national popular vote.