The Midwestern Reality: Wisconsin, The Midwestern Median

This is the sixth and final piece in our series of six features on the Midwestern Democratic decline where we explored consequential parts of the Midwest and the prevailing headwinds faced by the Democratic Party in the region. We’ll use each part to build on a pervasive and encompassing story of how the Midwest has shifted relative to the nation at large, and demonstrate how the region is becoming harder and harder for Democrats to hold.

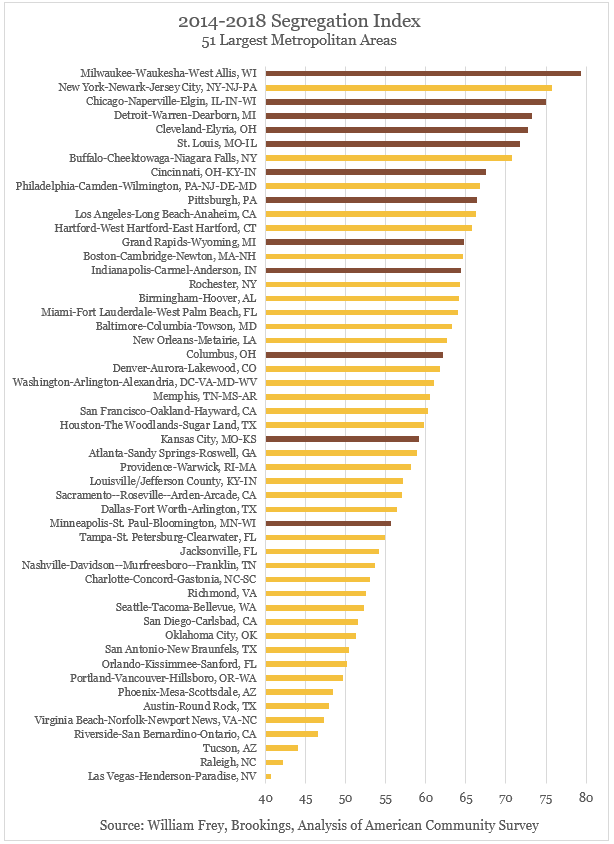

Of America’s 51 largest metropolitan areas, the most segregated isn’t in Alabama, Louisiana, or Texas. It’s not even in the South (the Birmingham-Hoover metropolitan area — the most segregated city in the South — ranks 17th overall). America’s most segregated major metro is centered on a city which has elected a Socialist as its mayor more recently than it has elected a Republican: Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

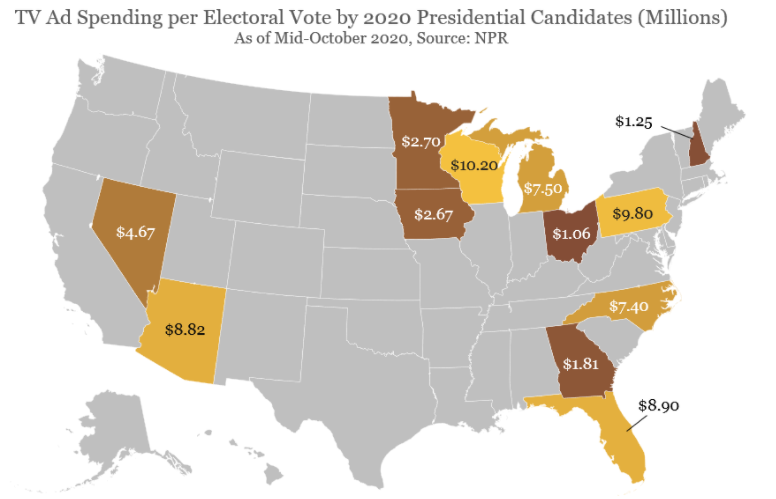

As we reach our conclusion of this series, it seems fitting that the story ends with Wisconsin. The state received the highest level of TV ad spending per electoral vote in the 2020 election, over $102 million, or $10.20 million for each of Wisconsin’s ten electoral votes. After Trump’s narrow margins in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin delivered him an electoral victory in 2016, Wisconsin was the most obvious source of Democrats’ fear: it was the whiter and more conservative state of the trio. A common refrain was that the Clinton campaign did not visit these states while the Trump campaign did, and that cost her these states. But that is not only inaccurate, but also oblivious to rigorous data showing that campaign visits would not have made a difference. The Clinton campaign did travel to all three states — Pennsylvania received 26 visits by the Clinton campaign, Michigan received eight, Wisconsin received five, and the Democratic National Convention was in Pennsylvania. Clinton herself did not go to Wisconsin (she did go to Michigan and Pennsylvania) because she was personally unpopular in the state and there was fear of “backfire.”

Research into whether Clinton’s visits (or lack thereof) impacted her margins in those states, has found it did not. Clinton’s ground game was not responsible for her election loss. Consider this: Clinton campaigned heavily in Pennsylvania, but still lost the state by more votes than she lost Michigan and Wisconsin combined. The same could be said of Florida, another state her campaign spent a lot of time in. Meanwhile, the Trump campaign journeyed to Virginia 18 times, Colorado 16 times, and New Mexico three times, while the Clinton campaign matched them five, three, and zero times respectively. But Trump handily lost all three states. Another thing often neglected is Clinton would have lost even had she won Wisconsin and Michigan… losing Pennsylvania, one of the states she visited the most, is what mattered.

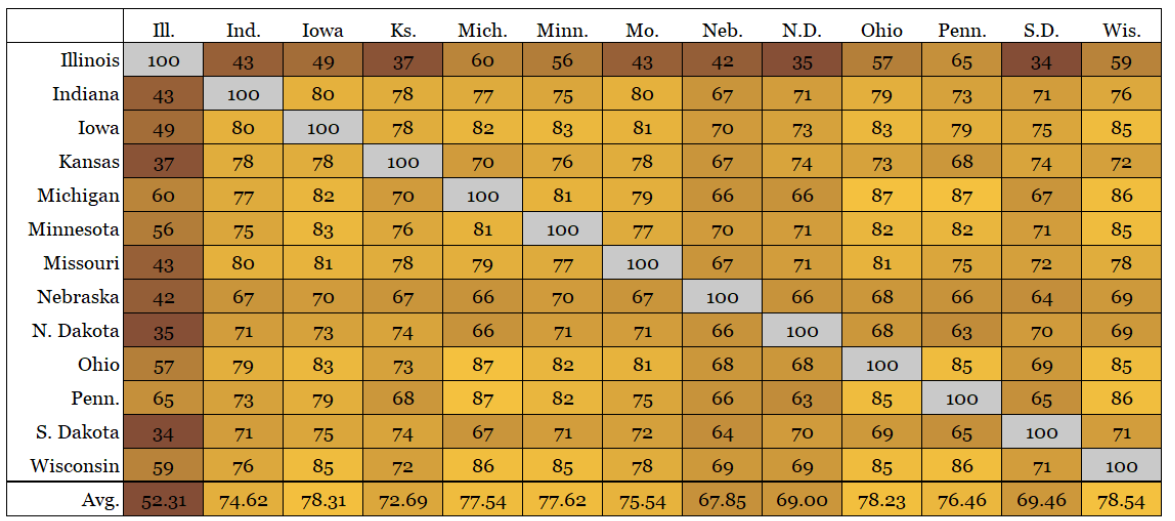

As it turns out, some states are just different, and vote in different ways. Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin are more Republican than the country as a whole. They are less educated than the country as a whole. They are whiter than the country as a whole. But while Pennsylvania is moderated by its half-Midwest, half-East Coast characteristics, and Michigan’s transition from blue-to-red-leaning state has been rapid, Wisconsin is the epitome of every compounding factor turning the Midwest away from Democrats. That is because, of the states in the Midwest, it is the most Midwestern; it is the most similar to the rest of the Midwestern states than any other. It’s special because of exactly how average it is.

Based on data compiled by The Economist around the 2020 election, in which they determined the demographic and political correlation between each state based on data such as the percentage of white voters, religiosity, and how rural the state is, we can identify which Midwestern states are most similar to every other:This data also confirms that the Midwest is the most homogenous region in the country. The states all hover around an average correlation of 73, with Illinois being a clear outlier.

Wisconsin edges out Iowa and Ohio as the state most reflective of every other state in the Midwest, which is why we will be bringing this story of the Midwest home with the Badger State. As we explored white voters and racial integration with Ohio and Iowa; dove into economic decline, urban power, and militia movements in Michigan and Minnesota; analyzed the partisan lean strength and elasticity that discourage diversion from these trends with Pennsylvania; and scrutinized the historical chronology of conservatism and the suburbs in Kansas and Nebraska, there has been a Wisconsin-sized hole tying all of these elements together.

There may be no state more reflective of America’s political divide than Wisconsin. It is a state trapped in brinkmanship and partisan rancour, a place where romanticization about middle America has enabled complacency and made this confrontation mainstream, where rage against the “elite” is alive and well, and where resentment against what America really looks like has fomented for decades. Like Kansas and much of the Scandinavian-and-German-settled Midwest before it, Wisconsin was born of progressive values, workers, unions, and education. But unlike Kansas, the state hemorrhages its most educated, leaving it with a population that is 81% non-Hispanic white, more than 20% over that of the nation overall, with relatively few white voters with a college education or more. This compounded Wisconsin’s segregation, as the late arrival of Black Americans into Milwaukee in the 1960s was met with resistance from the enclave of European descendents whose concentration in blue collar jobs faced economic headwinds as manufacturing declined.

No Wisconsinite encapsulates this story better than its former Republican governor, Scott Walker. In the 1980s, Walker, then a student at Marquette University, ran in the election for student government president against a liberal Chicagoan. Walker had blasted protest on campus, lead an anti-abortion group, and argued against divestment from apartheid South Africa. Surprising no one who knows anything about college campuses, Walker lost the election, and a couple years down the line, would drop out of college entirely. He immediately proceeded to run for the state assembly, losing an election in Milwaukee before moving to suburban Wauwatosa in 1993, which just so happened to be more conservative and holding a special election that year. Walker was then elected Milwaukee County Executive in 2002 and ultimately elected governor of Wisconsin in 2010 in an election that would also see Republican Ron Johnson unseat a Democrat for one of Wisconsin’s Senate seats and Republicans gain control of both chambers of Wisconsin’s state legislature. Walker would govern in the same vein as he campaigned. He opposed abortion even in cases of rape and incest, strenthened voter identification requirements, rejected Affordable Care Act funds to improve healthcare in the state, proposed a reduction in education funding, and pursued various other budget cuts that resulted in poor infrastructure and some of the worst roads in the country. Most famously, he supported a significant overhaul to collective bargaining for public employees in the state, an issue over which he would face a recall election in 2012 and become the only governor in American history to survive such an ordeal. When Walker launched a presidential campaign in 2016, he ranked among the most conservative candidates in the massive GOP primary field before burning out. In 2018, he narrowly lost reelection to a third term as Wisconsin’s governor to Democrat Tony Evers.

This college dropout who spent his political career crusading against education, against government spending on basic services and infrastructure, on undermining unions and abortion rights, and on trumpeting conservative social causes represents so much of what the state has become. It has renounced investment in higher education and healthcare, split blue collar and green-minded voters against each other, and accepted segregation and racial disparity on a level unlike any other in the nation. The plight of the general public in Wisconsin cuts universally — an opioid crisis and the highest prevalence of excessive drinking in the nation are a handful of several negative health consequences. White trauma and distrust is alive and well, manifesting in violent militia activity that is dangerously active and disturbingly comfortable in the state. Racism in the state and in the Midwest in general is often viewed through the lens of working class underprivileged whites. Working class whites who felt left behind, the racial resentment that grew as whites felt they were being replaced by those that looked different than they did, or white militia members tolerated or appreciated by police as they countered protesters. But this narrow lens obscures the more daunting statistics — like how Wisconsin quietly incarcerates more Black men per capita than any state.

The most segregated major city in the country is Milwaukee. It’s been dubbed the “worst city for Black Americans,” an epicenter of Wisconsin’s poor performance on education (Wisconsin boasts the largest achievement gap of any state), poverty (four out of five Black children in Wisconsin live in poverty), and incarceration (the state incarcerates twice as many Black men than the national average). Nearly eight in 10 Black residents in Milwaukee would need to move to a different neighborhood to be distributed as white residents are, almost twice the number of the nation’s least segregated major city. Milwaukee may be the worst offender, but it is not alone — the Midwest scores worse than any other region in segregation. Among the largest 51 metros, 12 are in the Midwest. Seven Midwestern cities make up the top ten most segregated major metropolitan areas in the country, while no city from the South or West is within the top ten. Of the 25 most segregated metropolitan areas in the country, regardless of size, 18 are in the Midwest.

This may be unexpected, but that’s the point — it’s glazed over as this idealized Midwest is touted as “nice” or “normal.” At best, “nice” has come to mean complacent to racism and anti-democratic behavior. At worst, “nice” is willfully ignorant, a way to excuse confronting deep-seated racial, educational, economic, and political issues.

So what does it all matter, you may ask. Evers won, Walker lost, Wisconsin would go on to vote for Joe Biden two years later. But it is exactly that kind of complacency that thrived under the Obama years that Democrats risk repeating following a narrow comeback in 2020. Had Joe Biden performed a point worse nationally, he would have lost Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin — and the election.Perhaps more stressful to American democracy, Biden actually ties with Trump in this scenario. He and Trump both wind up with 269 electoral votes, throwing the election to the House of Representatives, which — even if it were controlled by Democrats (not necessarily a given noting their incredibly slim margin in the House, and this scenario imagines Biden winning by 1% less) — would be conducted on a state-by-state basis, in which Republicans control delegations totaling a majority of states. Despite winning the popular vote by 4.5%, against a president who bungled a once-in-a-century health crisis, an economic crisis, and who was literally never above a 50% approval rating, the fact that Joe Biden barely won Wisconsin should raise serious concern from Democrats.

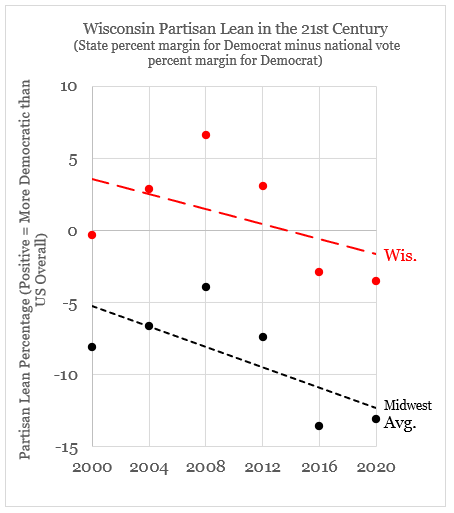

Even in 2020, an election in which it was the tipping-point state (the state providing the 270th electoral vote to the winner), Wisconsin was more Republican-leaning than the nation as a whole. This marked the largest Electoral College bias in over 70 years, with Biden needing to overcome a 3.5% Republican edge in the tipping-point state just to win the presidency. Obama may have won Wisconsin by 13.9% in 2008 (when he won by 7.3% nationally) and 7% in 2012 (when he won by 3.9% nationally), but, if anything, it is these elections that are the historical fluke compared to the ones that followed or preceded it. Al Gore and John Kerry both very narrowly won Wisconsin in 2000 and 2004 respectively, by 0.22% and 0.4% respectively. And in 2016 and 2020, the state was 2.9% and then 3.5% more Republican than the nation overall, a significant deficit for Democrats in what was the tipping-point state for them in both elections.

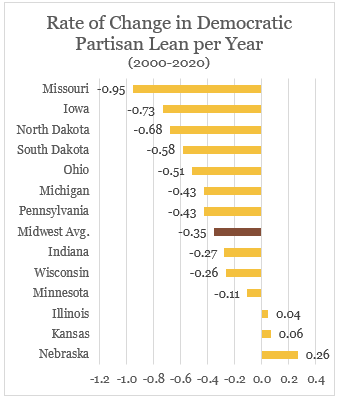

Wisconsin’s Democratic decline may not have been as rapid as Iowa or Ohio’s, or as stable as Pennsylvania’s, but that’s because the Badger State was always more competitive than it seemed, and because it has been trapped between an insurgent conservative base and its progressive history over the 21st century in which anti-elite sentiment loudly brewed. If 2018 or 2020 were any indication, the conservative base has proved victorious. The topline results don’t make it look that way, but as the state grows less than half as fast as the country overall, as its college graduates flee in droves, and its population remains one of the whitest in the country, the demographics reflect a homogenous state that looks very little like a Democratic electorate.

It is particularly concerning for Democrats that of the Midwestern states won by Obama twice and then won by Trump in 2016, the relative Democratic performance got worse in almost all of them. Iowa, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were all more Republican leaning in 2020 than in 2016. Michigan, though it remained Republican-leaning, is the only one of the five to become slightly less Republican leaning in 2020 compared to 2016. But, if this series has built towards anything, it’s that the pious focus on these states is holding Democrats back. These states need not be key to a Democratic-winning coalition, and the warning lights are flashing that they will not be for long — but there is a solution.

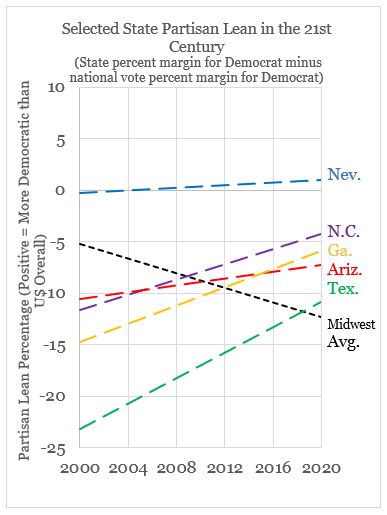

As FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley explained, “If the Frost Belt states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin continue to lean somewhat to the right of the country, that will benefit the GOP in the Electoral College — unless there is a counter-shift elsewhere in the Democrats’ favor. In 2020, for example, Biden narrowly carried traditionally Republican states like Arizona and Georgia. Those two states alone can’t make up for Democrats losing that Frost Belt trio, but Democratic improvement in those states and other places in the Sun Belt (whither “Blue Texas?”) could undo the Republicans’ current edge in the Electoral College.”

And, thanks to the fact that the Midwest is growing slower than much of the country, these states are losing electoral votes. Their influence is waning, and the fact that Joe Biden didn’t need to win several of them but still could have won the election is telling. A whole swath of states with diverse populations, rapid growth, and excited urbanites have moved into play for Democrats right as the Midwest turns against them. Arizona, Nevada, and Texas are some of the fastest growing states in the country. Nevada and Texas are both majority minority states. Georgia and North Carolina have large numbers of college graduates and urban centers ripe for prime time. Texas has 40 electoral votes, as of the 2020 census — that’s more than Ohio and Pennsylvania combined, and it’s moving towards Democrats at a clear consistency of 0.6% per year, which is faster than Michigan, Pennsylvania, or Wisconsin are moving against Democrats. All five of these Sun Belt states are now less Republican-leaning than the Midwest overall.

America changes. It grows, it moves, it makes decisions. And that means its states change too. Vermont went over a century without ever voting for the Democratic presidential candidate, as Georgia did without ever voting for the Republican. Colorado used to be one of the most conservative states in the country, while Idaho and Utah were swing states. Barack Obama won Indiana, Bill Clinton never won Virginia. Michael Dukakis won West Virginia without winning California and Richard Nixon won New Jersey while he lost Texas. The advantage we have today is the ability to see these changes progress over time, with the benefit of hindsight and data, acknowledging what states have shifted over a decade, and forecasting where others will shift in the next.

The Midwest has become more Republican, but it hasn’t changed dramatically in this century. Segregation, blue collar decline, and lagging education rates are not new to the Midwest. What is new is that the Republican Party has changed to prioritize this type of voter, and the Democratic Party has changed to prioritize a different kind. The Midwest is caught in between this transition, but it is by no means the only region at a turning point.

Five years ago, Republicans broke into the Midwest because they channeled a racial resentment that had fomented across states with a lot of non-college-educated whites. If Democrats spend their time desperately grasping for these Midwestern states back, they will do so at the peril of states where their party now resonates, which represent a diverse tapestry of their party’s urbanites, college-educated, non-white constituents. The Sun Belt’s opportunities aren’t as homogenous as those in the Midwest, but neither is the Democratic Party.

2020 demonstrated the strength of the headwinds Democrats are up against in the Midwest but also proved that clinging to this past is unnecessary. After 250 years dominating the electorate, it’s time to free the party — to free the country — from the control of white, non-college-educated voters. That starts by acknowledging the Midwestern reality: that it does not need to be the kingmaker of American political power, and most importantly, that it is not representative of America in the first place.