Veepmaxxing for Electoral Advantage

This is one of those articles that, despite having spent years and years working, researching, and writing in this area, feels a bit late. It would have been nice to write this article a week ago, when Vice President Kamala Harris was considering a handful of running mates, including several popular governors from more competitive states. She settled on Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, a choice we quantitatively recommended, but who may leave some wondering why she didn’t choose someone like Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro or Arizona Senator Mark Kelly. Surely both of those states are more clearly swing states and more necessary to a Harris victory in November than Minnesota – a state which, though it’s trended red, has not gone to the Republican presidential candidate in 50 years.

It’s a good question, one which has received plenty of study, and plenty of answers. From “it doesn’t really matter,” to “quite modest — perhaps two or three percentage points on average;” and from the advantage “is real and can affect the outcome of close presidential elections” to “only about 0.3 percent more,” there have been a number of attempts to assess the impact a running mate can have in their home state over the last several decades to various degrees of consistency (though most research clearly indicates any advantage is stronger in smaller states). Our philosophy, as something of experts on this ourselves (hey, check out Running Mates!), synthesizes all of this to assert two things: the first rule is always to do no harm, since a vice president is more likely to sink your ticket than affect the outcome of the election; and second, that a vice presidential pick can really only help on the margins. It might have made the difference in an election like 2000, but probably not in 1996 or 2012.

But, it’s become necessary to give this some additional empirical and quantitative heft to justify our assumptions, especially as we begin to rebuild our 2024 presidential election model given the race’s new dichotomy. Here’s what we found.

Does a Vice Presidential Nominee Affect the Margin in Their Home State?

Let’s start with our sample size. Though we often assess historical patterns across our projects, in building our comprehensive presidential and Senate models, we – generally – prefer to use elections from 2000 and on. This is a choice made based on some objective (and nonexclusive) assessments: there’s a pretty clear consistency in the shifts of demographics and the coalitions of the parties from 2000 and on, it’s a highly polarized period, it captures the era of “highly competitive elections” without starting with an incumbent ticket, and these six (soon to be seven) presidential elections tend to illuminate the consistent regional strengths of the parties without too much fluctuation. That means, for the sake of determining the effect a vice presidential candidate has in their home state, we will consider each running mate from 2000 to 2020.

This gives us 12 data points, starting with 2000’s Dick Cheney and Joe Lieberman and running through 2020’s Kamala Harris and Mike Pence. It’s not a large sample size, which means you should be skeptical about its margin for error, but it gets the job done.

For each vice presidential candidate, we took four points of data:

- The Electoral College votes their home state received in the year of the election (this serves as a proxy for population size proportionate to the nation as a whole)

- The ticket’s margin in their home state, adjusted by the national margin (so if the national popular vote was won by Democrats by 2%, but they won Colorado by 4%, that would mean they overperformed there by 2%, a positive value; whereas, if they only won Florida by 1%, that would mean they underperformed by 1% in Florida, which would be a negative value).

- A previous baseline, which is the performance of their party in the previous unaffected year, again adjusted by the national margin (an unaffected year is one in which no major party candidate was from their home state; so, for example, considering how Vice President Joe Biden may have boosted the Democratic vote share in Delaware in 2012, we would take a previous baseline of how Democrats did in Delaware 2004, as Biden was on the ticket in 2008 as well).

- A subsequent baseline, which is the performance of their party in the subsequent unaffected year, again adjusted by the national margin (in the same example as above, 2016 would be the subsequent year).

Here is that data:

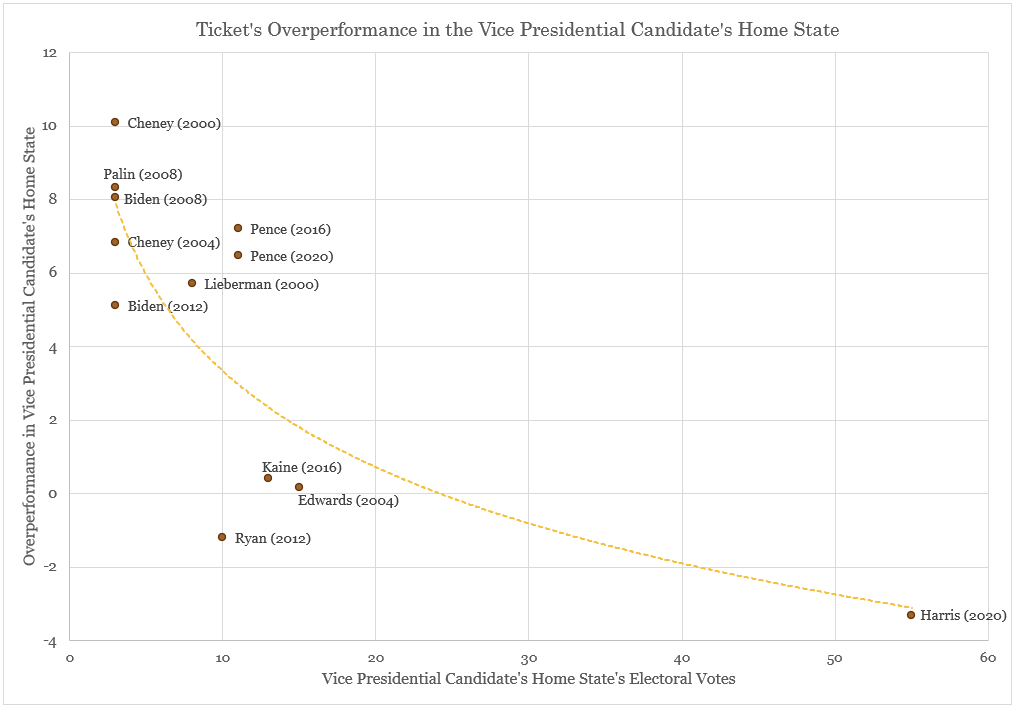

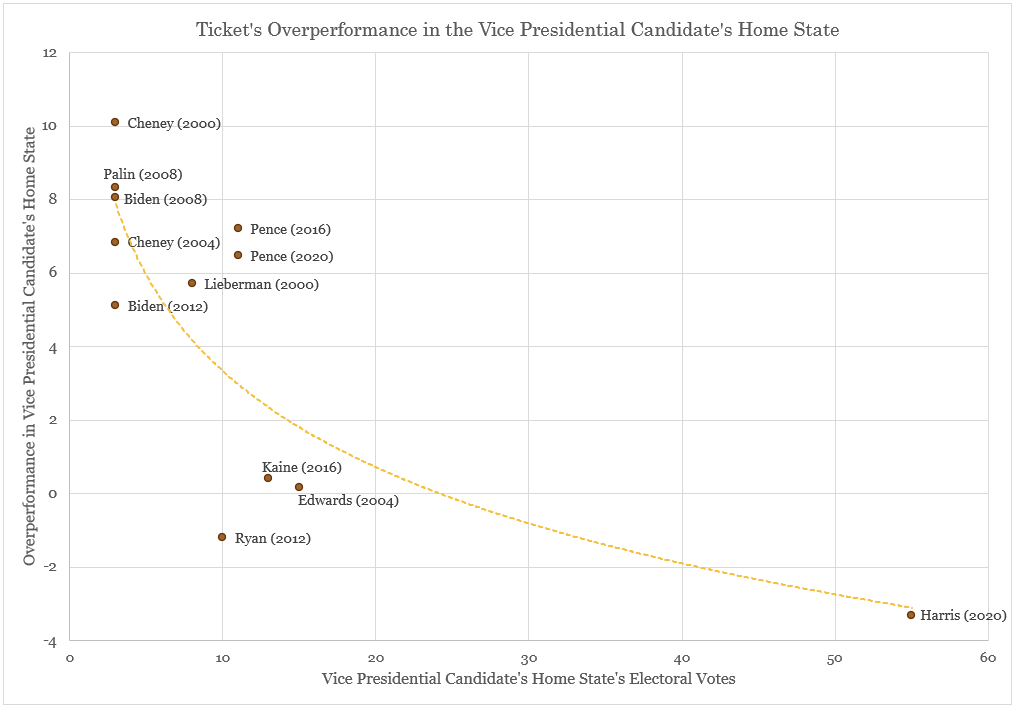

Using this data, we took the average of the previous unaffected year and the subsequent unaffected year in order to smooth out any ways the state may have been trending (for example, we wouldn’t want it to appear as if Democrat Tim Kaine, a Virginia native, clearly delivered a major advantage in Virginia if the state was already moving towards Democrats anyway). For the last three vice presidential candidates, we had no subsequent unaffected year, so it is reliant entirely on the previous unaffected year for comparison. Then we can take the adjusted performance of the ticket in the vice presidential nominee’s home state and subtract the adjusted average performance in that same state from the previous and subsequent years to find the ticket’s “overperformance” in that election. On average, there has been a 4.5% advantage in a vice presidential candidate’s home state (but we’re not done, please don’t use that number!).

This is similar to how Nate Silver assessed the home state effect of a vice presidential candidate back in 2012 with a couple exceptions. For one, again, our data size is more limited, intentionally constrained to 2000 and on (though we now have the 2012, 2016, and 2020 data points, which he did not yet). Second, we’re not going to stop there. We’re going to expand and do what he should have… giving you some more information by means of a regression model, including the degree to which more populated home states can affect the electoral impact.

If we plot our data we may notice something that seems somewhat intuitive:

Not only does the home state advantage evidently decline as that state gets larger, but the data seems to follow a logarithmic pattern rather than a linear one. This makes sense, as we’d expect the effect to be substantially more pronounced in smaller states, with diminishing marginal returns as states get larger. Running both a linear and logarithmic regression validate this, as – though both signal a statistically significant relationship and high degree of correlation – the coefficient of determination (R²) is higher when we run it as a logarithm:

The logarithmic model indicates that about 64% of the variation in the outcome of the ticket’s performance in the vice presidential candidate’s home state is explained by the variables at hand. This suggests that a running mate boosts the ticket in their home state by 12.03 points minus 3.77 multiplied by the natural log of their state’s electoral votes (note that no state has fewer than three electoral votes), or, according to this equation:

As an interim matter, this means the existing assumptions are largely true: the effect is much more pronounced in a smaller state, but a running mate can matter – if the election is close enough that it would come down to that state, and that state’s margin only needs to give so much more. This equation only explains about 64% of the variation, so we’d be inclined to weight the factor by that much to give you a more conservative estimate using the following formula:

Optimizing a Running Mate for Electoral Efficiency

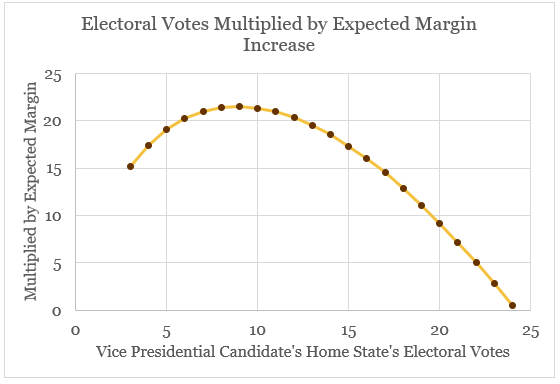

If we know that a vice presidential candidate’s effect on their home state’s margin gets smaller as the state becomes bigger, this suggests an optimized tradeoff point: how to – all other things equal – get the most electoral vote bang for your metaphorical buck. Picking a running mate from a state with only three electoral votes probably won’t help you a lot, even if they end up winning the ticket that state, whereas picking a running mate from a state with 30 electoral votes means the impact of the running mate is essentially nothing. In either situation, you’ve failed to maximize your utility – your ticket’s electoral efficiency.

So how should one “veepmax” for the most swing over the most electoral votes? By multiplying the expected margin increase from our above equation by the total number of electoral votes, we can determine the maximum electoral efficiency (getting the most margin across the most electoral votes).

It follows a pretty logical pattern: small states don’t deliver much electorally even if the net margin is large, so it increases pretty quickly before capping out and losing steam, ultimately degrading again around states larger than nine electoral votes.

Now let’s take, for example, Tim Walz. His home state – Minnesota – has ten electoral votes. An incredibly efficient pick: all else equal, it should increase the Democratic ticket’s margin in Minnesota by about 2.1%, and the state is worth a sizable share of electoral votes. It’d be better if the state were a swing state, to be sure, but the logic is relatively sound. Josh Shapiro, on the other hand, may have only helped in Pennsylvania (with its 19 electoral votes) by just about 0.58% That’s not nothing, and if Harris ends up losing the election by half a percent in Pennsylvania, we can’t pretend there was not an obvious solution, but that’s not a particularly likely event either.

There are a few more threads to pull on here, but they’re all pretty election specific, and would require adjusting for things like that election’s generic ballot and how that state has shifted over time. Rest assured, down the line, we’ll explore how to use this to optimally pick the candidate from the most efficient swing state to maximize your margin in a must win state – probably something to explore in a future version of our Vice Presidential Power Index (which uses a really crude version of this logic at the moment).

For now, rest assured, the evidence is pretty clear that running mates do matter, and should help in their home state, but it is – like many things – a matter of degree.