We Finally Have Our First Look at a “Best Popular Film” Award, and It Does Not Look Promising

The year was 2018, and the Oscars had a problem. Well, the Oscars always seem to have a problem, but this time they felt like they had a solution, too. Coming off of the least watched Oscars telecast in history, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences decided they needed to do something splashy to attract a modern viewing audience and announced the creation of the Academy Award for Outstanding Achievement in Popular Film, a new category that would, presumably, have highlighted and rewarded the box office-dominating sci-fi and superhero films that had taken over filmgoing culture in the 2010s, and that the Academy had tended to neglect in recent awards seasons.

The idea was quickly trashed by industry observers and Academy voters alike, a reaction that led the Academy to quickly scrap the award, saying that they needed to “examine and seek additional input” regarding the category. Despite then-Academy President John Bailey’s suggestion that it could always be reintroduced, AMPAS has instead resorted to more indirect routes to attract a more “mainstream” film watching audience, some that have meshed well with Oscars tradition (Black Panther and Joker were nominated for Best Picture in 2018 and 2019, respectively) and others that were unmitigated disasters (remember 2022’s fan voted awards?).

While I too thought the creation of the Outstanding Achievement in Popular Film Award – or OAPF, for brevity’s sake – would have been a mistake, it still remains a tantalizing what if. The backlash was so swift that AMPAS never actually released any details regarding the award (i.e., how many films would have been nominated or what would have qualified as a “popular film”) outside of noting that films in this category would still be eligible for Best Picture. For a while it seemed like we’d never get a true sense of how exactly this award was supposed to work…until now.

Earlier this year, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the scandal-stained organization that owned and voted on the Golden Globe Awards, sold their show to Dick Clark Productions in an attempt to drag it out of the reputational wilderness in which it currently resides. You can read all about the HFPA’s controversies and the Globes’ restructuring elsewhere, but, for our purposes the most important outcome of this sale is that it has led to the creation of two new categories: Best Performance in a Stand-Up Comedy, and the Golden Globe for Cinematic and Box Office Achievement.

While the stand-up award seems all well and good (there’s no way it won’t be going to John Mulaney this year, right?), the Cinematic and Box Office Achievement award (which I will mercifully abbreviate to CBOA) has emerged as the most interesting, and in some ways most depressing, to talk about. The qualification criteria for the award are relatively straightforward: to be eligible, a film must have made at least $150 million at the box office, at least $100 million of which must have been generated domestically (films released on streaming platforms will also be considered, but no specific viewership threshold was announced by the Globes). Eight films will be nominated for this award, and all of them will also be eligible (although not necessarily nominated) for Best Most Picture – Drama and Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, the Globes’ Best Picture equivalents.

And the Nominees Are… Not Surprising

The day this award was announced, Isaiah Washington of Next Best Picture published an article listing all of the films that would be eligible for this award given their box office numbers (streamers still tend to keep their stats a secret), giving us some real idea of how this kind of an award would actually work. The first thing that hit me while I was reading Washington’s piece was how boring the field felt – part of the excitement of awards shows is not knowing who a given body is going to nominate, let alone choose as a winner, and whittling down a field to include what are already the most popular and, by extension, over discussed movies in the world only leaves so much room for discussion and surprise.

But what I found most striking was how redundant the award felt, especially given that its nominees would also be eligible for the Globes’ Best Picture-style awards. By my estimation, there are at least three movies in the CBOA field that have a very good chance of being nominated for either Best Drama or Best Comedy or Musical. The most obvious are Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, a critical juggernaut that’s currently the third-highest grossing movie worldwide this year and the second-highest grossing R-rated movie of all time, and Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, which also received very strong reviews and became a legitimate cultural phenomenon on the way to generating the highest grossing of any movie so far this year. It’s virtually impossible to imagine a world in which neither of those movies are not nominated in their respective Best Picture awards at the Globes and for Best Picture at the Oscars, to say nothing of the accolades that their casts, writers, directors and below the line staff will likely receive as well. Awards’ bodies’ reticence to nominate animated films for their top awards may make Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse a bit of a dark horse, (2010’s Toy Story 3 was the last to get a best picture nod), but its awards campaign has attracted support from influential commentators like Variety’s Clayton Davis, and it should be a favorite for most Animated Film awards this season, with Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron standing out as its only true competition.

Looked at from one angle, the presence of these three heavyweights in the CBOA field should legitimize the award as proof that movies that make a lot of money can be well-made and well-respected too. But the effect I suspect it will actually have is to create an even bigger gulf between this power trio and the other five films that will be nominated for the award.

Think about it in terms of the Oscar for Best International Feature. While the Golden Globes don’t allow films nominated for its Best Foreign Film Award to be nominated for its Best Motion Picture awards, the Academy has no such qualms when it comes to Best Picture Oscar. In fact, the past half-decade has been proven to be something of a golden age for international recognition at the Oscars – since 2018, at least one non-English language film has been nominated for Best Picture. In all but one of those years, the foreign language film nominated for Best Picture was also nominated for Best International Feature, and wound up winning the category against four other films that were not nominated for Best Picture (Minari, a 2020/21 Korean-language Best Picture nominee that was ineligible for Best International Feature because it was produced in the United States, is the lone exception).

This trend makes sense. In fact, it’s a textbook example of the transitive property. If Roma, Parasite, Drive My Car, and All Quiet on the Western Front were good enough to be nominated for Best Picture and the four Best International Feature nominees they competed against at their respective ceremonies were not, then logic states that the former films should have won Best International Feature. This is something that has held true in every year that a film was nominated for both awards, and one that has held true for Up and Toy Story 3, the only films to be nominated for both Best Picture and Best Animated Feature. As such, there’s no reason to believe that it should work any differently for the Golden Globes’ CBOA. Sure, the presence of three possible Best Motion Picture contenders instead of just one muddies things up a bit, but even so, what is ostensibly intended as an eight nominee race would become a two or three nominee race.

Granted, awards shows are arbitrary celebrations of art, glamor, and ego, and are therefore not bound by mathematical rules. But to award a film that is not nominated for Best Motion Picture the CBOA would be to concede that the intent of the award is to recognize something other than the best movie in the category, and doing so would further call the legitimacy of an already controversial awards show into question, forcing some Golden Globes executive to give a sweaty explanation as to why Oppenheimer and Barbie are excellent films that somehow fall short of whatever “box office achievement” is.

Is this Box Office Excellent Enough for You?

But as absurd as this whole situation is, it did get me to thinking: could 2023 be an outlier? The success of Oppenheimer and Barbie were notable because of how different they were from the CGI-heavy superhero epics that ruled the box office for most of the 2010s. Sure, Barbie is based on an existing IP, and yes, Oppenheimer was heavily based on a biography of an already famous person, but neither were a legacy sequel or a superhero film. They were, for all intents and purposes, original films that nonetheless found a large audience. Would a CBOA or OAPF have made more sense in the years when the gap between what made money at the box office and won prestigious awards seemed larger, and could it make sense in the future?

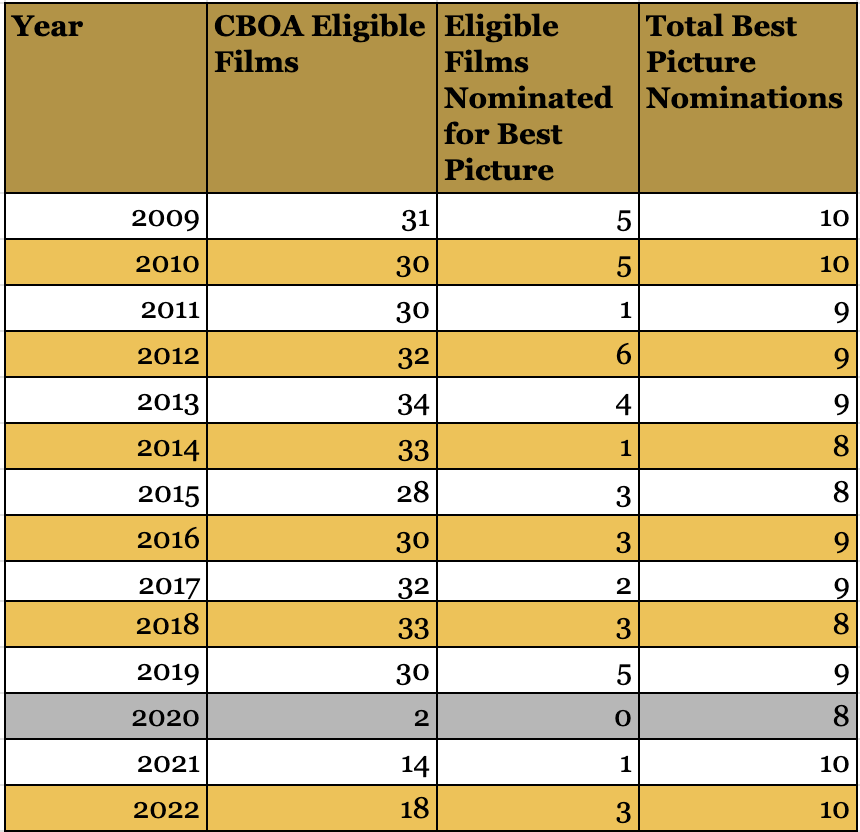

To try and make sense of this, I decided to piggy-back off of Washington’s work and figure out what films would have been eligible for a CBOA/OAPF in the past. To do so, I looked at Box Office Mojo’s yearly worldwide box office numbers for every year since 2009, and compiled a list of every film that met the Golden Globes’ current CBOA criteria to try and see how many of these movies were eventually nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, thereby rendering the other award moot. I chose 2009 because that’s the first year the Academy expanded the Best Picture field from five to ten, ostensibly in response to The Dark Knight not receiving a Best Picture nomination the previous year, and I chose to focus on the Oscars field instead of the Golden Globes because, like everyone else, I have very little respect for the Globes.

Before I get into the results of my very simple statistical study, I should note that there is one big outlier in the data set: 2020, when cinemas were shuttered thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. Only two films would have qualified under the Golden Globes’ rules for CBOA that year (Bad Boys for Life and Sonic the Hedgehog, for anyone curious), and given that we don’t have any reliable streaming data that could give us some idea of what would have also been eligible in that terrible year, I decided to throw it out entirely. 2021, the year in which theaters began to reopen, albeit slowly and under restrictions, only saw 14 films qualify, and while that remains lower than the average number of 28.8, it was similar enough to 2022’s 18 for it to be included.

It’s important to point out the 2020 outlier and the specific numbers for 2021 and 2022 for two reasons. The first is because, within this dataset, all three are in fact outliers. Every year between 2009 and 2019, at least 30 films would have been eligible under CBOA years, the one exception being 2015, in which 28 films would have been eligible. The second reason is that it’s important to acknowledge that we may never reach these numbers again in a post-COVID and post-streaming world. An era in which the top box office performers in a given year average closer to $1.5 billion instead of just over $1 billion may have necessitated a larger threshold for what’s considered a “box office achievement.” But, since the CBOA rules are the only ones we have available to us, they’re the ones we’ll follow.

Now that all of those caveats and concessions are out of the way, on to the data. While the number of eligible films per year is fairly consistent, the number of Best Picture nominees within these fields is not. Three years (2011, 2014, and the weird, still semi-locked down 2021) saw only one film that met the CBOA criteria land a nomination (The Help, American Sniper, and Dune respectively), while the record for highest number of CBOA eligible nominees is held by 2012, with six. So while there’s no clear identifiable trend here, there is one very important fact: every non-locked down Oscars year between 2009 and 2022 has seen at least one CBOA eligible film nominated for Best Picture, which means, given historical precedent and the transitive property, the winner of an Oscars equivalent for CBOA would have been fairly predictable.

While this fact alone already proves my point about the award’s superfluousness, it’s worth pointing out that in most years, and on average, the Oscars nominated multiple CBOA eligible films for Best Picture. In fact, the average number of CBOA-eligible Best Picture nominees for a given Oscars year turns out to be just over 3.2. If you assume that, like nearly every other category, the Oscars’ OAPF field would be limited to five nominees, that means that Best Picture nominees would count for literally half of the films’ nominated – once again demonstrating the category’s redundancy.

The numbers also seem to imply that the Best Picture field itself is more balanced in terms of high-performing box office hits and modestly selling critical darlings than one might assume. In fact, a little over 35% of Best Picture nominees in the analyzed years are films that have made at least $150 million worldwide and $100 million domestically – and thus, by the Golden Globes’ definition, a “box office achievement.”

18 Million Viewers in the Hand are Worth 50 Million in the Bush

So what can we glean from all of this? On the whole, it seems that the hand wringing over the Oscars not nominating enough box office hits is slightly exaggerated – people are seeing at least some of these movies, even if they’re not seeing them in the same numbers that they are other films. The problem that CBOA/OAPF seems designed to solved isn’t the absence of movies that make $150 million – it’s the absence of certain kinds of movies that make $150 million, which sport certain kinds of fan bases that take it upon themselves to generate certain forms of hype and online discussion, which the Academy and Golden Globes then hope to convert into television viewership.

This quest is futile for two reasons. First, as we demonstrated, the likelihood of an MCU or DC film winning a CBOA/OAPF are likely quite low, given that they will probably be facing a film that is already nominated for Best Picture, which risks alienating two broad demographics. The first are the serious cinephiles and awards show fans who watch these ceremonies every year, and who will feel like they’ve been cheapened by the creation of a category designed to do little else but boost viewership. The other will be the rabid fans of big IP-based blockbusters who, if they even decide to tune into the shows in the first place, will walk away frustrated when their favorite movies lose to a film that’s already nominated for Best Picture. The solution to keeping the blockbusters fans engaged is simple – let one of “their” movies win the award – but allowing it to do so over another Best Picture nominee will anger the already skeptical cinephiles, and create a negative press cycle sowing doubts about the legitimacy of these ceremonies in the process. And that’s not even getting into how having specialized “popular film” categories may dissuade voters from nominating a Black Panther or a Top Gun: Maverick for Best Picture in the first place, given that they would have the chance to reward it in a lesser category instead.

If that sounds like a lot of assumptions and conjecture on my part, well, that’s because it is. But assumptions and conjecture are exactly what the Academy and the Golden Globes are relying on when they say they think these popular film awards will bring back viewers, which leads us into the second reason for their futility: while it’s certainly possible that the nominated films have contributed to the Oscars’ and Golden Globes’ decreasing viewership, the most likely explanation is the very nature of the show’s themselves. All awards shows represent a dated form of entertainment (star-studded variety specials) broadcast on a dated medium (non-sports live TV) that modern audiences simply do not have the need or appetite for.

It’s not just that they have access to hours of entertainment, most of which is presented without commercial interruption – it’s that the mystique of Hollywood and celebrity in general is as thin as it’s ever been. You don’t need to watch the Oscars to see your favorite movie star (assuming you even have one) in a fancy outfit – you can go straight to their Instagram, where they have not only posted that outfit, but posted nearly every noteworthy outfit they’ve worn over the past year as well. You don’t even need a group like the Academy to tell you what movies are worth watching either – every streaming service has algorithms perfectly tailored to your taste that pushes movies and TV shows that some of those pesky mathematical laws have determined you will already like.

I don’t want this piece to sound disdainful – if you’ve read my writing for a while, you know that I love the Oscars. But the Academy and its peer organizations are at a crossroads, and they have to decide whether or not to chase an audience that they’ll never capture or consider scaling down and embracing the niche viewers who will always care about them. I’m not entirely sure what that latter option looks like – that’s for much richer people who wear tuxedos much more frequently than I do – but I do know what it doesn’t look like. And it certainly doesn’t look like this.