When Will We See a Blue Texas?

In 2018, upstart Democratic Congressman Beto O’Rourke launched what – at first – seemed like a longshot campaign against incumbent Republican Senator Ted Cruz in a state long recognized as something of a spiritual home for the Republican Party. Democrats had not won a statewide office in Texas since 1994, but O’Rourke built up momentum and garnered national attention, and closed the gap: by Election Day Republicans acknowledged serious risk. The prospect of winning a race in Florida and losing an incumbent in the race in Texas was genuine.

But perhaps this shouldn’t have been so surprising.. As expected, Texas governor-turned-president George W. Bush carried the Lone Star State twice by over 20% margins in 2000 and 2004. But even in 2008 – a Democratic landslide election – Texas still went for John McCain by about 12% over Barack Obama (19% to the “right” of the nation overall, accounting for partisan lean). And in 2012, Texas opted for Mitt Romney over Barack Obama by a 16% margin (20% to the “right” of the nation overall when accounting for partisan lean). But 2016 was different; Hillary Clinton lost the state by less than 9%. Longtime Republican stronghold Harris County (home to Houston) went from being a tossup in the Obama years (he never won it by more than 2%) to demonstrably Democratic (Clinton carried it by over 12%). Hispanic voters and younger voters preferred Clinton – and in a state demonstrably more Hispanic and younger than the nation overall, this worked to her favor, even if much of this was lost in the attention focused on Clinton’s underperformance in the Midwest and the states that lost her the election.

Two years later, when O’Rourke challenged Cruz, people started to notice. Democrats really did have a chance to break into Texas’ statewide politics. Of course, O’Rourke ended up losing that election. But he did so by only 2.6% of the vote, the closest margin in a Texas Senate race since 1978. The confluence of Cruz’s unpopularity, a Democratic-leaning environment (the generic ballot consistently had Democrats nationally overperforming Republicans by 6-8% as the election neared), and the state’s rapidly changing demography all brought O’Rourke within a stone’s throw of victory. This was unthinkable to Democrats when Obama was president.

Jump forward again two years from 2018 and what seemed like a fluke in a Democratic-leaning year suddenly becomes a consistent trend. Joe Biden lost Texas by only 5.6% to an incumbent Republican president, while Iowa and Ohio went for Trump by 8%, New Hampshire for Biden by 7%, Virginia by Biden by 10%, Colorado for Biden by 13.5%. In other words, Texas was now closer than the quintessential swing states of the Obama years. In 2020, only eight states were closer than Texas. It wasn’t quite a swing state, but given time and the right national environment, Democrats were getting close.

Come Hell or High Water

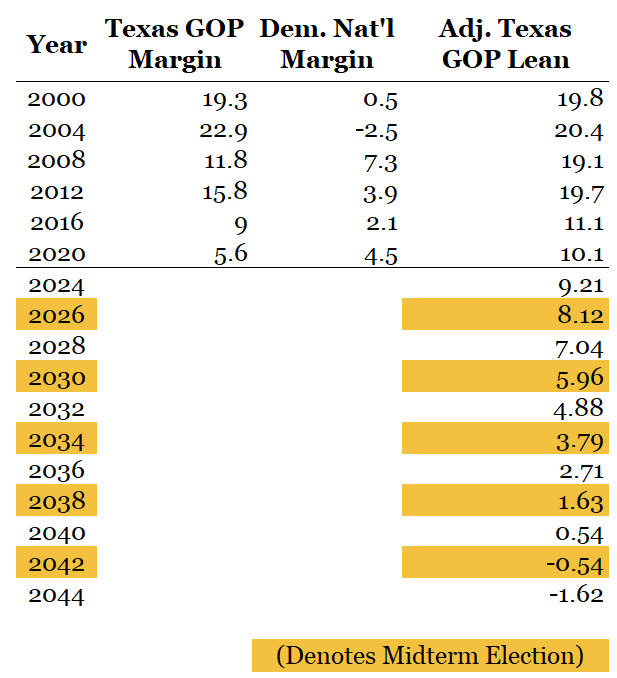

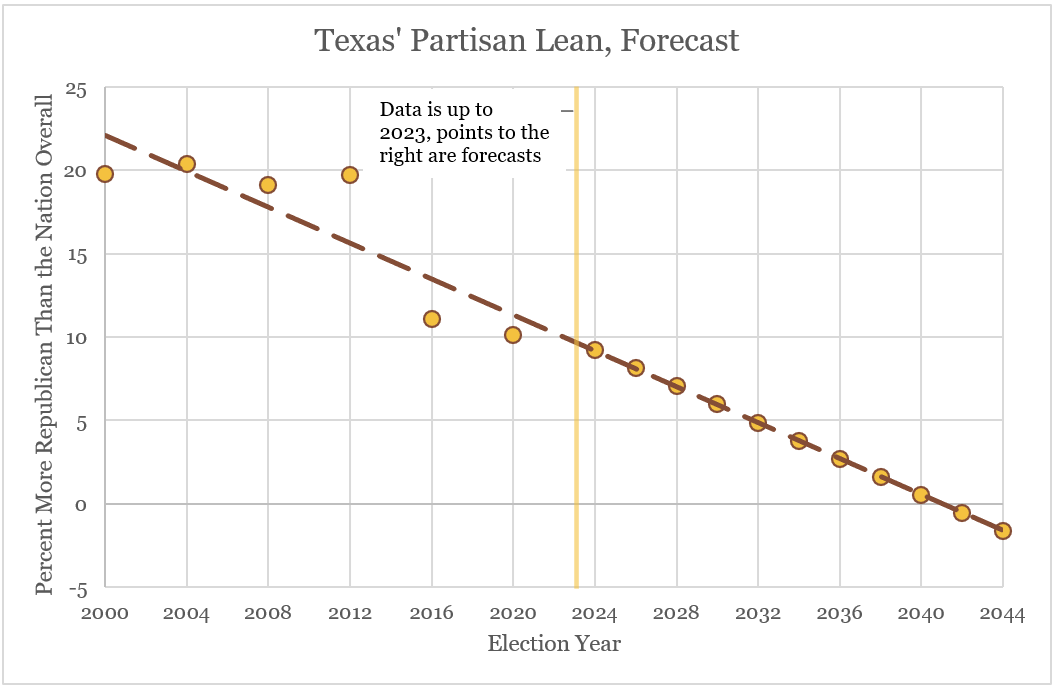

Extrapolating based on Texas’ presidential margins in the 21st century, we can broadly forecast Texas’ shift towards the Democratic Party over time. Though it seems instinctive to ditch the information from the 2000 and 2004 elections, given that Bush almost certainly had a home state advantage in both cycles, these data points are more or less in line with the state’s partisan lean in the Obama election years. This data shows that from 2000-2020, the state went from being around 20 points more Republican than the country overall to only 10 points more Republican (this makes sense – recall Biden lost Texas by 5.6%, while carrying the nation by 4.5% – meaning the state is 10.1% more Republican than the nation overall).

The linear fit here is strong – the state has clearly moved leftwards over time. This suggests that, if the state continues at this rate, it will get about half a point more Democratic every year. This projects that the state will be Democratic-leaning by the 2042 midterms, about 20 years from now. Of course, this doesn’t mean that’s when it’s going to go blue – it’ll likely happen well before that. Only one presidential election since 2000 has been Republican leaning (that was in 2004, when Bush won the popular vote by 2.5%); on average, presidential elections in the 21st century have leaned Democratic by 2.6% and from 2012-2020, they’ve leaned Democratic by 3.5%. This likely makes 2026 or 2028 the earliest a Democrat could carry Texas. Why? Let’s walk this forward.

The largest national margins for the Democratic Party in the 21st century have been 8.6% and 8% in midterms (2018 and 2006, respectively) and 7.3% at the presidential level (in 2008). Unless Joe Biden carries the nation by nearly 10% in 2024 (unlikely in our age of heightened partisanship, even given an incumbent president’s advantages), this puts Texas out of reach. A fractured Republican Party resulting in a serious third party challenge would change all of this and almost certainly put Texas in Biden’s column, but we’re ignoring that for now. However, if Biden were to lose reelection and Democratic turnout surged as it did the last time there was a Republican in the White House, Texas is almost certainly in play in the 2026 midterms. Democrats would need to do only as well as they did in 2018 to have a serious chance of capturing a Senate seat or the governor’s mansion.

2028’s presidential election may still be a stretch unless a Democrat can secure Obama-in-2008 level margins, though this is unlikely given this’ll either be against an incumbent Republican president or after two terms of a Democratic president. But if a certain unpopular former president wins election to a nonconsecutive term in 2024, and is then ineligible to be elected to a third term in 2028, the environment may mirror that of 2008.

This probably makes 2032 the earliest point a Democrat could reasonably be able to carry the Lone Star State. They’d have to do about as well as Biden did in 2020 for it to be a toss-up, but that’s still well within the range of possibility given the Republican Party’s homogenous coalition that has been consistently incapable of generating a national majority. Even once you consider the eccentricities and oddities of individual elections, instead note only the fact the Democratic Party tends to score a mid-sized win at least once a decade. With that in mind, come hell or high water, it is incredibly unlikely – unless there is a major turnaround in the state’s demographic shifts and growth rate (which would, itself, be quite unlikely) – that by the end of the 2030s a Democrat won’t have won a statewide office or secured the Lone Star State’s electoral votes.