A Proposal for a Fair Presidential Primary System

Think it’s too soon to be talking about presidential primaries? Well, the Democratic Party is already trying to shift the order of the states in the primary calendar by moving South Carolina up to first place and throwing Iowa to the curb. A couple weeks ago, we explained why this may be a better choice, if not quite the fair choice any national party should aim for. That’s because, as we wrote there, the national party, or any individual state, selecting the order of the states is inherently unfair. It makes many states go early, while other states necessarily go later; one state – or a few states – have to go first; and one state – or a few states – always has to go last.

Any single state is unreflective of the national electorate or the Democratic Party. Iowa and New Hampshire are disproportionately white, South Carolina has a lot of Black voters but few college educated voters, New York and New Jersey have a good mix of all demographics and voters but are siloed in media markets too expensive to be accessible to the retail campaigns we’ve grown accustomed to. The point I’m trying to make is choosing any individual state to go first is unfair. It necessarily elevates a single state’s interests and voters above the voters of anyone else (ethanol is definitely… definitely… great policy… right, Iowa? Postrider 2024!) and means the later states are afterthoughts in a field that is pretty well winnowed by the time the primary reaches them.

We’re here to show you there’s a better way. A way that takes the strengths of the current system and combines them with an underlying principle of equity – through the only real means possible.

Why the Current System Works

To do that, we have to explain what the current primary system gets right, mostly in an effort to explain why a “one giant national primary on one day” system is a bad idea.

The advantages of the modern primary system as you know it – with Iowa and New Hampshire going first, followed by Nevada and South Carolina, and the other states going in a somewhat loose and unstable order following that over a matter of 5-6 months, are more manifest than you may assume given the frequent critique.

For starters, intimacy; most of the early states are quite small. Iowa has about 3.2 million people, New Hampshire has around 1.4 million, and Nevada has about 3.2 million. These small populations make it easier for candidates to meet a high proportion of the voters and build out personal relationships and networks statewide. Iowa and New Hampshire act as testing grounds for candidates because they really have to get to know the voters in these states to separate themselves from the rest of the pack, and intimate moments between candidates and voters often allow America to see these candidates as humans instead of as far-off concepts. (Remember Hillary Clinton’s show of emotion in New Hampshire during the 2008 campaign as she lamented the sexism she experienced?). New Hampshire is also the fifth smallest state by area in the union, making it comparatively easy to traverse by retail-campaign-oriented candidates who may not have extensive financial resources to fall back on. Being hyper-focused on a few hundred thousand voters may seem perverse to national audiences who don’t get the same attention from candidates, but it does allow an assessment of a candidate’s appeal on a human-to-human level. Can they speak with empathy to individual Americans? Can they draw a crowd? And, if they can’t convince the voters they get to know intimately, how could they ever hope to convince a national audience that only sees a candidate on television?

Alluded to in that first strength of the current primary system is affordability and communication. Candidates are not all made financially equal, and having smaller states with relatively affordable media markets gives more of a fighting chance to low-budget campaigns that may nonetheless have national appeal. Iowa has several media markets in the state, including Des Moines, Cedar Rapids, Omaha, and Sioux City. Nevada has the Las Vegas and Reno markets and part of the Salt Lake City one too. South Carolina has seven. New Hampshire is kind of the odd duck out here, as they have no media market of their own, split between the Burlington, Vermont; Portland, Maine; and the expensive Boston, Massachusetts media markets. Though Boston and Las Vegas are both big, more expensive markets (Las Vegas is relatively affordable for its size, Boston not so much), the spattering of small media markets across these states helps candidates of different wallet sizes compete with the Michael Bloombergs of the world. That hotels tend to be relatively affordable in the cities in all of these states compared to say those in California or New York is a benefit here too, as candidates (and their staff) will be spending a lot of time there. Of the four early states, the largest metropolitan area is Las Vegas, which – in terms of convenience – is unmatched in the volume of hotel rooms and accommodations for out-of-state visitors.

Another strength the current system emphasizes is endurance. Our primary process is long. And I’m not just talking about the five months between the first primary and the last… most candidates spend more time campaigning in the year before the first primary than they ever will in the actual year of the primary. Joe Biden announced his campaign for president in April of 2019 – about nine months before the Iowa caucuses in 2020, a period of time about four times longer than the actual time after Iowa it took for Biden to become the presumptive nominee (two months). To make it to the convention, you need to have real staying power, tenacity, and resources – being able to make it the eight or nine months to the first primary and then slog it out one contest to the next is a near-impossible task that foreshadows the nightmarish travel and calendrical expectations of a general election candidate (and future president).

Finally, a strength I want to stress here is diversity. The current system’s problem is it puts too much emphasis on only a handful of states, especially on Iowa and New Hampshire. Though this could undeniably be done better, and our proposal will aim to do so, there is a certain sense to then having a state from the West (Nevada) and the South (South Carolina) go next, so one state from each region is in the first four. Then states across the union are sprinkled in on varying days. Though the heavily-weighted Iowa and New Hampshire processes dominate unfairly in the current system, diversifying how candidates focus on different regions and types of voters is important. Joe Biden was able to succeed by focusing on the South in a way that Pete Buttigieg could not. But finding out which candidate can do well across all regions is a strength that the current system stumbles into clumsily. It’s about halfway there.

There’s a lot to love about the modern primary system – but it’s also unfair and ridiculous that the same states always go first.

What We’re Ignoring: Delegates

There is something inherently absurd about reforming the entire primary system without even mentioning how the parties award their delegates and how that might be changed. This article is leaning into that absurdity for two reasons. First, the goal here is to set a foundational system on the bottom in terms of the order of the states that the parties can place their own mechanisms and rules on top of. This will be a proposal neutral to the procedural and political considerations of open vs. closed primaries, superdelegates, and which states deserve more delegates than others. In that vein, the second reason this proposal ignores delegates is that if we start interfering with that it messes with the two fundamentally different systems the two parties have that are designed to cater to their respective electorates.

Democrats have a system requiring each candidate to meet a threshold (15% of the statewide vote) at which point they’re awarded delegates proportionate to any other candidate that meets that threshold. This works to Democrats’ favor by selecting for a consensus-building candidate who appeals to a broad spectrum of the diverse and multifaceted Democratic coalition. It is a requirement that their nominee play well across their base that includes groups as different as Millennials, union members, Black protestants, and establishment types. That’s why the Democratic nominee tends to have an “80%” vibe – there’s always a fifth of the party that’s really down on them, but most of the 80% have simply determined they’re “good enough.” This is the price of such a broad coalition. But, then again, if you found a candidate that appealed only to your 10% slice of the Democratic electorate, chances are they only appeal to 5% of the national electorate… so they’re probably not a great candidate for your party anyway. At least, this way, Democrats pretty reliably put up someone that a vast majority of the party can mostly get behind. Democrats also determine how many delegates each state gets based not only on size but also on how well the Democratic presidential candidate did there in the last few presidential elections. States that hold off by scheduling their primary until later in the season get more delegates too. Finally, Democrats have some additional delegates called “superdelegates” who are typically elected officials and party officials, who also get a say if the convention is contested. The superdelegate system emerged in the wake of a number of high profile Democratic presidential flops in the 1960s-1970s as a failsafe to make sure there was at least some input from Democrats who actually had success being elected to office when the party’s base only loosely rallied behind a nationally-unpopular candidate (like 1972’s George McGovern). That being said, superdelegates have never once altered the popularly-elected result of a Democratic Primary. Over the course of several decades, Democrats have built a system at the national level that patches as many holes in their coalition as they could identify, tweaking it a bit from one election to another, and relying on some technocratic formulas to determine which states get more delegates than others.

The Republican system, on the other hand, is much more devolved and slightly less math-heavy. Though the Republicans also award states more delegates if they have Republican governors, legislatures, U.S. Senators, House representatives, and if they went for the Republican presidential candidate in the last presidential election, they have no superdelegate equivalent. This system, in contrast to the Democrats’ national performance considerations in determining each state’s delegates, rewards state-level party growth. But the most substantive difference is how candidates actually win the delegates in each state. This is largely left up to the states, but many states use winner-take-all or winner-take-most systems to award delegates, meaning most or all delegates go to whoever wins a plurality of the state. For example, in the 2016 South Carolina Republican presidential primary, Donald Trump won only 32.5% of the vote – but because Marco Rubio (23%), Ted Cruz (22%), Jeb Bush (8%), John Kasich (8%), and Ben Carson (7%) split the remaining vote and no one got more votes than Trump, Trump walked away with all 50 delegates from the state despite receiving fewer than a third of all the votes cast. This is how Trump, who received only about 45% of all votes cast in the 2016 Republican presidential primaries, ended up with an outright majority of 1,441 delegates (almost three times more than any other candidate). The advantage to the winner-take-all system embraced by many states on the Republican side is that it recognizes the homogeneity of the party’s base makes it more amenable to any given nominee and gets the dominant candidate out of the furnace early, avoiding a brutal slog to the end that has become commonplace in Democratic primaries. Historically, it’s been very effective! It’s also particularly vulnerable to a candidate who has a very motivated plurality of voters, like Trump, Ronald Reagan, or – to pick from the other side – Bernie Sanders.

Creating a neutral system means empowering the parties to embrace their differences, while requiring a nationally instituted order of states that is fair to every state and voter. In other words, our proposal seeks to be fair to every state from a nonpartisan and national standpoint, by upsetting the longstanding precedence of primary priority, and parties may then place their hands on the scale by choosing how to award delegates.

The Postrider Plan

So how would we do it? Randomly!

Let me start with a personal anecdote. Growing up, when my sister and I integrated with a new stepfamily of two more children in my preteen years, a “chore wheel” system was implemented where, every night, one kid would set the table, one would clear the table, one would load the dishwasher, and one would have the night off. Every day, it’d rotate. Seems fair, right? Wrong! My sister and I were on an absurd “Monday/Tuesday with mom; Wednesday/Thursday with dad; alternating Friday-Sundays” schedule that was not fun for anyone. But our stepbrothers were on an alternating week schedule. See the problem? Sometimes we’d have to pick up a job on the “free” night, sometimes rotating it every day meant someone was stuck with dishwasher duty twice in a row while another had a day off twice in a row, and a lot of resentment built up. Not exactly what you want when you’re trying to force-integrate two sets of children into living together in a house that one set was not a member of. It was unfair, unproductive, and actively harmful to morale. After a few brutal months of that, I realized there was one way that could actually be fair: a lottery. Every night, the children who were at the house would simply draw their name when a certain chore was given out. Some people got stuck with dishwashing duty three days in a row; but the chance was always there they could get stuck with the night off three days in a row too… and everyone stopped complaining. This is my earliest memory of my mind clicking like this – and a political scientist was born!

Now that you know my origin story (and have a great idea for your own family going forward – seriously, incentivizing them with the prospect of a chance of no chores works! Find me a child who won’t happily take a 50/50 chance of doing all the chores compared to doing none and watching their sibling do it instead), let’s apply a similar lottery to the party primaries.

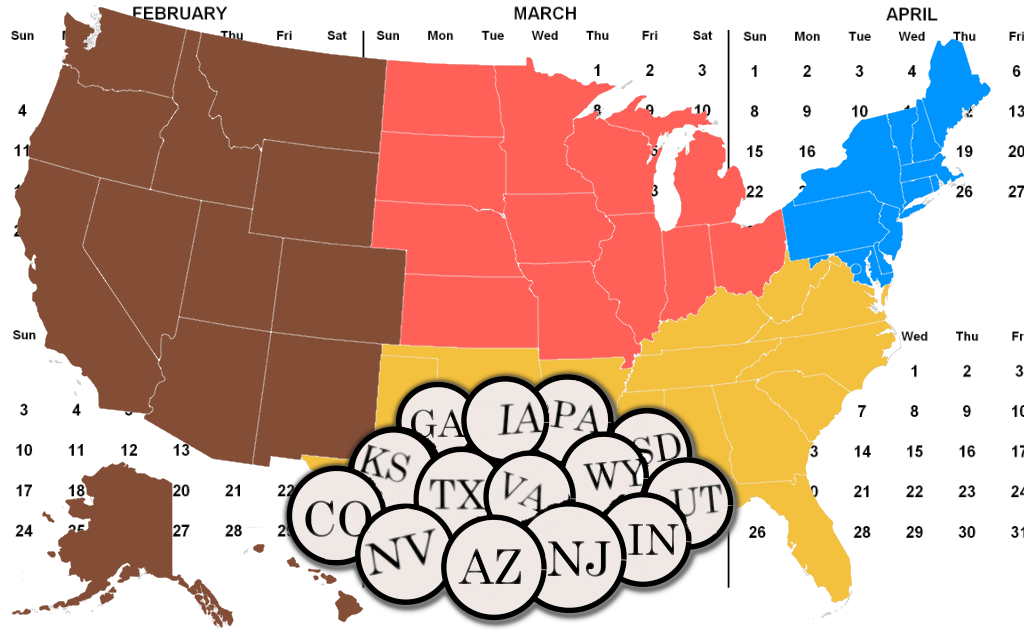

In the January before the year of the election (like the upcoming January 2023), about the same time as the convening of the new Congress – but in a far more televised event – some ceremonial position or committee (think along the lines of the president pro tempore of the Senate; the FEC; or the mayor of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania for all I care) emcees a drawing to determine the order of the primary in the upcoming presidential cycle.

Before whatever ceremonial body has been selected are four bingo cages (or something like what Powerball uses). Each of them contain the states pertaining to each of the four Census regions. Okay – now pause, this deserves an explanation.

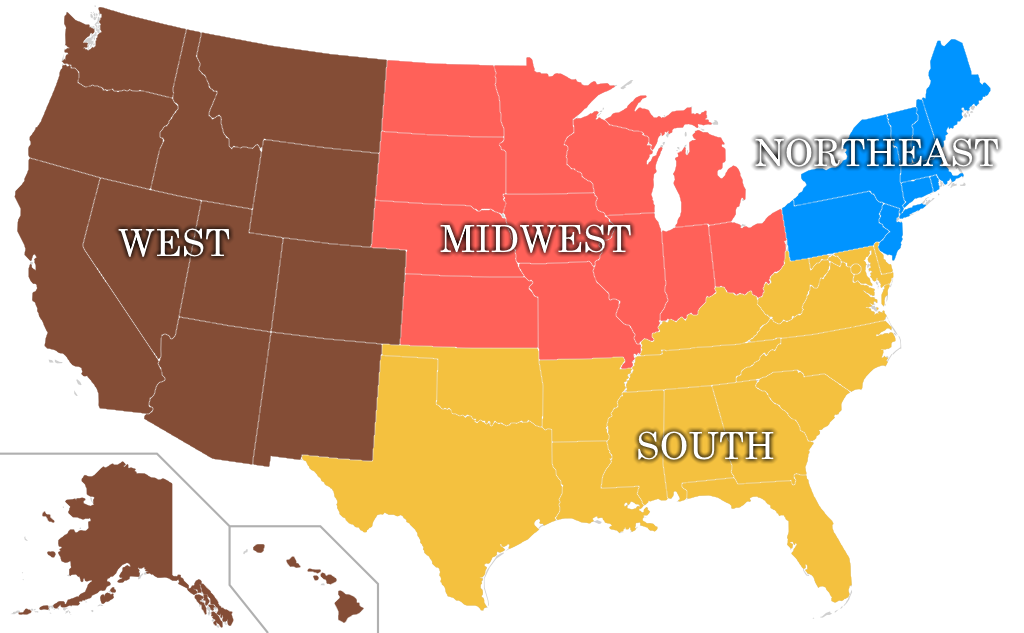

The United States has four Census regions: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. With a few quirks (I will fight you if you think Delaware belongs in the “South”), these are pretty well known – and the states within them have a lot of cultural, economic, and demographic similarities. The Midwest has its own connotations, as does the South – and most people tend to at least grasp that. It’s also a widely used classification system by businesses, politicos, and government officials.

The idea here is to draw from each region a state to determine the first four simultaneous primaries. But there is a problem that my jab at Delaware being included in the South will help correct: the Census regions aren’t quite equal. According to the Census Bureau, there are 16 states and the District of Columbia in the South, but only nine states in the Northeast. The Midwest has 12, and the West has 13. That’s okay, this is an easy fix. Move Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia (which is nestled on the Maryland side of the Potomac River anyway) into the Northeast, and each region now has a similar number of states.

You’ll note I included DC in the states here. What gives? Well, given that their voters do get to cast a vote in presidential elections (but have no representation in Congress, hence the righteously petty “taxation without representation” license plates in the District), we will count them as a state in this primary system. And, as antidemocratic and wrong as it is not to give citizens of any other United States territory like Puerto Rico or Guam similar say (and statehood), we’re living in the real world where they cannot vote for president in November, and thus will be uncomfortably talked around in this proposal.

After a state is drawn at random from each pool, we know the first four primaries, one per region. Say they are Maine (Northeast), Tennessee (South), Minnesota (Midwest), and Idaho (West). These four states will each go on the first primary day. After this, the drawing continues to determine the following week’s primaries, then the next, and so on so that each week in the upcoming year’s primary schedule will have at least one state from each region until we get to the end. By virtue of having one more state than any other region, one state in the South will go last (but hey, Southerners, give up a state and you won’t have to go last).I’m looking forward to the “Virginia could go into the Northeast” discourse I’ve accidentally waded into on the wrong side before… let us know how strongly you feel about it at contact@thepostrider.com!

This means the entire primary process will take 14 weeks in the year of the election, so if it started at the beginning of February it’d go until mid-May. The requirement for a presidential candidate to endure and persist throughout a grueling primary schedule is intentionally kept alive.

What Does This Do Better?

This is a similar system to that once endorsed by the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS), or the interregional plan once proposed by Michigan Congressman Sandy Levin, or the regional plan suggested by Crystal Ball’s Larry Sabato. However, these plans have features like the entire region voting in a given day or still giving small states like Iowa or New Hampshire the opportunity to go before the rest, or giving one specific region the advantage by going first every cycle. Each of these create problems in a way this proposal does not – so let’s unpack that too.

By having one state within each region go first, the country is well balanced in terms of regional significance and state significance. There will never be a situation where one region goes first or gets the benefit of presidential candidates’ attention before any other. A strength highlighted upfront was that the current system at least lets one state from each region of the country go in the first four. Our proposal would have one from each region go simultaneously every week until the end. None of this bias towards corn growing voters in Iowa at the expense of hospitality workers in Nevada; if a candidate can’t survive the months of lead up into the Iowa caucuses, they probably never paid much attention to Latino voters in Nevada or Black voters in South Carolina, and that’s a problem.

A critique of a regional system like those suggested by Sabato and the NASS is that it creates an expensive regionally-dominating system (where an entire single region goes first, or goes after a couple early states). That would be a bad system: giving a candidate that appeals in the South the power to acquire an overwhelming number of delegates simply by virtue of an entire region being drawn first. That’s why our proposal differs by drawing a state from each region, as opposed to drawing a single region to have all 13 of its states go on the same days. The candidates can pick which states they’ll prioritize and how best to play across all four of them. Take the 2020 presidential primary, for example – but imagine Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina go on the same day. You can see how Biden might avoid Iowa and New Hampshire, while Sanders and Warren prioritize New Hampshire or Nevada, and Buttigieg focuses on Iowa. There is no single demographic or ideological obstacle in Iowa or South Carolina that filters out a bunch of otherwise strong candidates.

By making it a lottery based on each state within each region, the prospect of a single region always going first is eliminated, as that would be unwieldy (to have the Midwest, or a state in the Midwest, selected to go first three cycles in a row), but the prospect of a single individual state being selected to go first multiple cycles in a row is always the same. We don’t really care if Indiana is drawn as the first state in the Midwestern region three cycles in a row, because there are three other states each cycle on the same day (and this is certainly no less fair than Iowa always going first).

This random draw element, even if it creates the potential for a certain state to go two cycles in a row, also avoids the opposite kind of bias. By creating a rotating system that simply goes in order, even within each region (so that Utah will go first out of the West, and next cycle will always be Idaho, followed by Colorado, in a 13-cycle, 48-year loop), we bias the system in favor of whichever candidate is the right age and tied to the right state at the right time. That isn’t fair either. A 30-year-old politician from California but who grew up in Pennsylvania and who knows both of those states will both be selected to go first in nine cycles will bide their time for 36 years. Better for everyone if the strongest national candidate is not because they knew the cycles in advance and instead is determined by the needs of the party, the issues of the times, and how well a candidate can cater to multiple states and many different kinds of voters.

Our proposed system also keeps the emphasis on retail politics and candidate-voter intimacy that is a strength of the modern system. By giving each state within a region an equal chance of being drawn, as opposed to a system which would advantage a given state by going first based on population (giving California a higher probability of being drawn than Wyoming, for example), smaller states have an outsized influence. This is probably the least traditionally “fair” element of our proposal, but there is a logic to this. For one, the presidential election via the Electoral College disproportionately benefits smaller states to begin with – so we’re trying to rebalance in favor of what the national map will look like. Second, we like the idea that candidates will have to – in at least one or two regions – really form a relationship with the voters. There are 22 states and the District of Columbia that have a number of electoral votes (six) less than or equal to Iowa. Given that includes 8/13 in the West, 6/12 in our revised Northeast, 5/12 in the Midwest, and 3/14 in the South, the odds are good that a small state gets outsized attention.

Now you may protest that there is a chance that California, New York, Texas, and Illinois – four of the six largest states in the country – are all drawn to go first. Yes, there is a slim chance of that happening, and a first draw of those states would benefit well-funded candidates (as these are also expensive states to campaign in, given their size and media markets). But the only thing more unfair than this is to proactively select against big states, which is a battle we’ve been having in the United States since the beginning (and which, given the control of the Senate, the Electoral College, and thus the Supreme Court, the big states have handily lost). If that’s the luck of the draw one cycle, that is no more unfair than letting four small states go first as we do now. Besides, the largest states in the country are far more diverse and look much more like the country overall than the small states. In an ideal situation, your first four states would include a couple midsized states, a big state, and a small state, but without any one party or any one state proactively deciding a specific state “deserves” to go first. Our proposal achieves that by virtue of equal regions and randomized states.

A Truly National Process

Why not use six regions like the aforementioned Congressman Levin proposed? Well, if we used six regions, the entire process would be over in about nine weeks, cutting down the primary’s time by a month – which is an advantage or disadvantage, depending on who you ask. It’d also require some more specific drawing of political lines. The Bureau of Economic Analysis has six regions, but one of those only has four states – and Minnesota and Wisconsin should probably be together, as should Arizona and Nevada, DC and Connecticut, and Colorado and New Mexico. Whether you agree or disagree with those placements, my point is that this is much more up for debate as to the Census’ definition of “West” or “Midwest” which, with a little wiggle room, are pretty well understood.

Why do it by Census regions at all? I argued earlier that regions are understood to represent different economic, political, demographic, and cultural histories. Presidential tickets tend to split along regional lines, different candidates prioritize different regions, and – very generally speaking – voters will be more similar within given regions than with those outside of them. I’ve extolled the value of not picking a singular state to go first (even if at random), and picking one from each Census region finds a good balance. If this system were in effect for the 2020 Democratic primaries, and the same four states all went on one day, it would have been much more obvious that Joe Biden was a stronger candidate than his fourth place finish in Iowa and his fifth place finish in New Hampshire seemed to indicate. His overwhelming first place finish in South Carolina and runner-up status in Nevada would have prevented a lot of write-offs.

Organizing the selection of four states at random by Census regions also emphasizes the fact that the United States is big and varied; to be a successful presidential candidate means playing to voters across the entire country. Though we strive not to inject partisan concerns into this national system and are only trying to design a system that is fair to every state while keeping the strengths of the modern one, it is likely this design would also serve as a moderating influence on candidates, making for stronger national candidates to begin with. That’s because more liberal Republican primary voters in the Northeast will have a say at the same time as more right-wing Republican primary voters in the Midwest. And more conservative Democratic voters in the South will be balanced out by more progressive Democratic voters in the West. The counterbalancing of all of these voters will tend to favor a candidate who can appeal to all of the party’s voters – someone at the center of their own party – and thus closer to the national median voter, as opposed to the base of a party’s primary.If game theory and party primaries is your thing, check out this old piece on the problem with the current primary system and how game theory shows it tends to strongly disadvantage the challenging party against an incumbent president.

Finally, there’s a performative and patriotic sentiment to this proposal. By holding a televised drawing, it builds anticipation and excitement for every state, as any of them could be given a unique chance to shine. Think of something like the roll call at the party conventions – every state can have a moment to stress why they’d be excited to host the candidates in the first or second week, and excited voters across each state could host watch parties for the drawing and cheer as their state is named and they find out where they are in the calendar.

A political union of fifty states (and one federal district), united in purpose and government, the United States is often torn apart or overshadowed by the machinations of few. When it comes to electing a president, only a handful of states get any attention and have any hope of affecting the outcome. But reframing our selection of the president as something each and every state could and should have an equal say in seems overdue. Bringing America back together is an inherently political task, and one often best accomplished by political means. Our presidential primaries are one way to bring us a little closer together by insisting each state is but one of many, and that no state, or any kind of voter, or any region, must always be ahead of any other. A little randomness could go a long way.