Romneyland: Part I — Believe in America

This fictional (and, I hope, relatively believable!) exploration of the world in which Mitt Romney won the 2012 presidential election was inspired by many things, including Romney: A Reckoning by McKay Coppins, our own Running Mates podcast, and a deep appreciation for the retiring Senator Romney’s life and career. Please enjoy Part I.

Part I (2011-2012) | Part II (2013-2014) | Part III (2015-2016) | Part IV (2017-2021)

Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney wasn’t sure what it was, but something about that morning made him feel optimistic. Sure, his naturally optimistic disposition – the product of an unworried upbringing – often left him underwhelmed, but he couldn’t help but think that November 6, 2012, was going to be different.

Since he entered the race in June of 2011, Romney had adhered to a slow and steady campaign strategy, weathering the flame-of-the-week candidacies of Texas Governor Rick Perry, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Minnesota Representative Michele Bachmann, and businessman Herman Cain. Though a late-minute surge from Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum caused some consternation, Romney’s strategy of keeping his head down and sticking to his message of job creation paved the way for a clear polling lead by the time the early states were through. Pundits attributed this steady momentum to the fact Romney consolidated supporters of former Ambassador to China (and former Governor of Utah) Jon Huntsman and those who had been hoping for a run by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie well before New Hampshire by showcasing a pragmatic approach to foreign policy and social policy early on. Of course, Romney also hinted to Huntsman that he would receive a prominent spot in his cabinet (read: Secretary of State), should the Romney administration come to be.

What’s more, Romney felt good about what had happened beyond his control. The economic recovery from the Great Recession had been slow and uneven. Romney didn’t root for a recession, but he couldn’t help but acknowledge the political advantage it gave him. Progressive discontent with the moderate policies of incumbent Democratic President Barack Obama – especially after the 2010 midterms caused Republicans to sweep the House – inspired an unusually strong primary challenge to the sitting president from little-known Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders earlier that year. Obama didn’t lose a state, but an embarrassingly low 60% of the vote in New Hampshire was enough to force the president to embrace some of Sanders’ more progressive rhetoric in hope of winning back young voters. Not that it worked – the DNC attempted to cancel several Democratic primaries, which just prompted outrage. And the “Bernie Bros” (as they came to be derisively called) became a thorn in the president’s side for the rest of the election – Democrats feared many of them would simply stay home or vote for a third party. Once the worse-than-expected job report came in for May 2012, seeing a spike in layoffs and unemployment (turns out the job gains from earlier in the year were overestimated too), Romney felt invigorated in his campaign’s message that the incumbent’s approach was hamstringing the recovery. For both his sake, and for his country’s, Romney was thankful Hurricane Sandy – like most hurricanes – turned eastward as it barrelled past the Eastern Seaboard.

Throughout the week leading up to Election Day, Romney had looked back at his campaign with pride. He’d made some mistakes, but felt they tended to make him stronger overall. He was thankful that Ohio Senator Rob Portman agreed to join him as his running mate, something about the Ohio connection felt right for a campaign that was putting such great emphasis on revitalizing the auto industry and the struggling Midwest. It helped that Portman also had a lot of Washington and foreign policy experience – two things Romney didn’t. More than anything, he was also – funnily enough – grateful that he caught the flu in mid-September, when he was supposed to attend a $50,000-a-plate fundraiser. It turned out someone planned on filming the reception, and that realization had forced him to be more cognizant about his off-the-cuff remarks both on the trail, in private, and in the presidential debates. His evident foreign policy weaknesses, which Jon Huntsman had taken him to task for in a debate the year before, had led Romney to prioritize studying up for the third and final presidential debate on foreign policy, and it showed. He made sure to master the chronology of the attack in Benghazi and caught the president off guard by effectively attacking the administration for its own foreign policy naivety; the attack on Obama’s “red line” in Syria was the highlight of the night, as Americans had grown increasingly weary of any commitments to foreign conflicts over the last four years.

The momentum coming out of the final debate was palpable. President Obama struggled to break past the 46% approval rating he’d entered the year with, and most predicted that would make this a tight race. Romney opted to maintain his focus on Ohio and made a closing pitch there, but also took a daring swing through Florida and Virginia (his team wanted him to be in Pennsylvania, a state he all-but-ignored throughout the campaign). By the time Romney settled in with his family at 7 PM to watch the results come in that night, he felt nervous.

“The first states are always boring,” his oldest son, Tagg, would repeat what seemed like every ten minutes. Fair enough, Indiana and Kentucky were both called for Romney and Vermont for Obama just after 7 PM, no surprises there. Florida, North Carolina, and Virginia were the East Coast states Romney put all his chips on anyway. By 8 PM, they were all still too close to call – but Romney noticed he did better than expected in Georgia. If he squinted, he could make out that this portended an overperformance in North Carolina and Florida (“because they’re next to each other? That’s not enough of a reason…” he’d think to himself), but knew realistically he’d have to wait until at least 9 PM, when results from Colorado would begin to trickle in and a clear picture of the race in Ohio would have formed.

By 9:30 PM, Ohio remained too close to call. The networks had finally called North Carolina for Romney, as well as Pennsylvania for Obama, but Romney did better than he thought in the Keystone State, holding the president under a 3% margin (“maybe I should’ve swung through after all,” he wondered to himself). Wisconsin was too close to call too, and Romney wondered if he’d have had a better chance if he’d have gone with Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan as his running mate (“then again, his air of arrogance when talking to working class voters and his skepticism of unions would be a non-starter… I wonder if I’d actually have done worse in the state had he been on the ticket…”). And Romney felt a sense of remorse that he didn’t win Michigan, the state his father, George, was governor of – where Romney himself had spent much of his youth. But he felt some resolve in that it looked like Obama would carry the state by less than 5%.

The wait for Ohio, Colorado, and whatever was going to come out of Florida and Virginia was interminable. Romney opted to go for a walk with his wife, Ann, to clear his head. “We’ll be back by 10, when the polls close in Iowa,” he told his family. Once outside, Mitt couldn’t help himself, as he continued to nitpick at the peculiarities from each race he’d spent now nearly three hours obsessing over. “How can it be that Michigan is going to end up closer than North Carolina, but New Hampshire is an Obama blowout?” he asked his wife rhetorically. “Youth turnout is down in Michigan and Florida but up in Colorado?” he kept murmuring. She kept quiet, knowing, more than anything, Mitt just needed some air. After several minutes of pacing, Romney’s phone began to buzz. It was Portman. “You’re going to lose Wisconsin, the networks are going to announce it any minute – but Ohio’s still in play, we just might not know tonight.” Frustrated, Romney grabs Ann’s hand and builds up the resolve to go back inside and tell his family they better settle in for the long haul.

As Romney and Ann enter the room again, Mitt notices the networks have awarded him Utah and Montana just as the clock hits 10 (“still no surprises tonight,” he thinks to himself). As 11 PM rolls around, the map has barely budged. Iowa and Nevada have joined Colorado, Florida, Ohio and Virginia as too close to call. As if an intentional onslaught, networks call the West Coast outright just after the hour, delivering 74 electoral votes to Obama. Mitt hadn’t expected to win any of them, but he couldn’t help but grimace at the overkill. By midnight, he’d won Arizona. A lot was riding on the seven uncalled states – Alaska, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Nevada, Ohio, and Virginia – winning just a couple of them (or Florida alone) would throw the election to Obama, but Romney needed a near sweep to claim victory. “Still,” he thought, “the fact that Colorado and Iowa are still in play is a good sign.” At 2 AM, as Romney turned in for the night, the last text he saw read: “Lost Colorado. Just called Ohio for you though. 221-260.”

Don’t Miss a Thing: Get Our Content in Your Inbox!

When Romney woke up, he felt an odd calm. A quick glance at his texts confirmed over the course of the night he’d won Iowa and Alaska, but lost Nevada. 230-266, with Virginia and Florida still on the board; Romney needed to win them both. Almost resigned to his fate, he largely ignored politics that morning – only occasionally eavesdropping on his team enough to catch that the gender gap had not meaningfully grown in this election and that youth turnout was down. “Maybe Democratic support had been sapped by the distaste felt by young Sanders supporters, seems like a lot of them did not turn out last night,” Romney thought to himself and smiled a little. It wasn’t until that afternoon that the networks (other than MSNBC, who dithered) called Florida for Romney. 259-266, it all came down to Virginia.

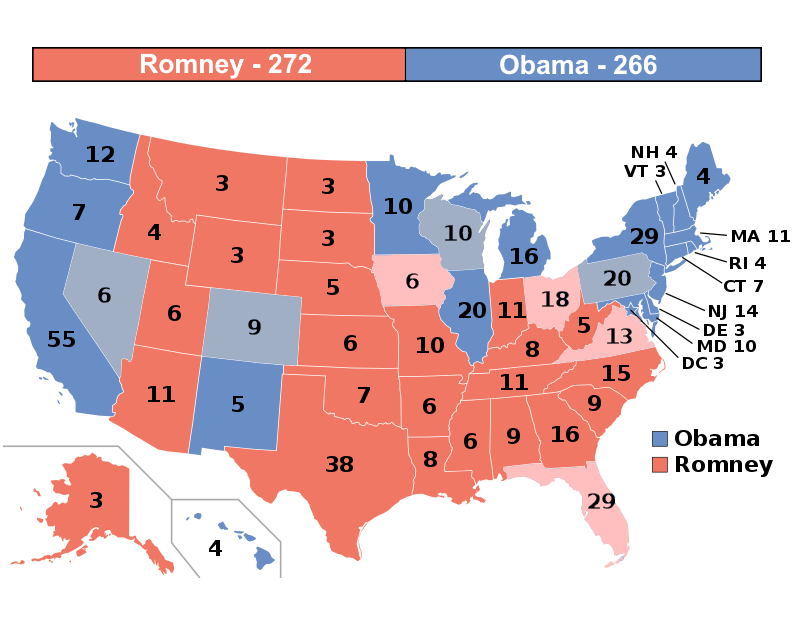

It wasn’t until Thursday afternoon that Romney received the call from the president. 272-266, one of the narrowest Electoral College margins of all time, and it looked like Romney would carry the popular vote nationally by just shy of 1%. But even after he heard the concession, Romney couldn’t help but feel awe – by a margin of just 11,000 votes, the Old Dominion had delivered Romney the presidency. “To think I almost went to Pennsylvania instead,” he recalled, as he let out the largest exhale he’d had in weeks.

Once again, we hope you enjoyed this fictional exploration of the world in which Mitt Romney won the 2012 presidential election. This is part one of four, follow on to the next part here.

If you have thoughts, think things would have played out a little (or a lot) differently, or are curious to see an exploration of any other possibilities, please reach out to us, we’d love to hear from you!