Romneyland: Part III — A United Tomorrow

This fictional (and, I hope, relatively believable!) exploration of the world in which Mitt Romney won the 2012 presidential election was inspired by many things, including Romney: A Reckoning by McKay Coppins, our own Running Mates podcast, and a deep appreciation for the retiring Senator Romney’s life and career. Please enjoy Part III.

Part I (2011-2012) | Part II (2013-2014) | Part III (2015-2016) | Part IV (2017-2021)

“Well, here we are again,” President Romney remarked to his family around 6 PM Mountain Time with a wry smile, as they gathered in their Utah home on the night of November 8, 2016. He had tried to hide it, but the Romney clan knew him too well: he was nervous. He’d felt confident four years ago, and that was a nailbiter, so what did the fact he felt nervous tonight portend?

Just a year ago, Romney felt good about reelection. His 51-seat Senate majority (in back-to-back runoffs, Democrats had kept Louisiana and Republicans kept Georgia) had allowed the president to divert his attention towards reelection as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (buoyed by House Speaker John Boehner, who put down an internal revolt by Freedom Caucus hardliners with the help of Romney’s support) handled the day-to-day in Washington. Legislative successes were still hard to come by, but the Republican Congress managed to constrain the government’s budget and deficit, tighten education policy, and avoid any shutdowns or major showdowns. Romney and McConnell needed to rely on Democrats to make headway on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) after a surprising number of Republicans came out against it in mid-2015 (Senate Republicans, who were a bit embarrassed by the schism in their own caucus, felt some jubilation when videos came out of the Democrats’ loudest TPP critic, Ohio’s Sherrod Brown, ensnared in a screaming match with Colorado’s Michael Bennet).

Romney had grown increasingly frustrated with Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid over the last year, as Reid had vigorously opposed the president on the TPP. At least Romney understood why; Reid had always been an ally to the labor unions,who hated the agreement. What really soured the relationship was Reid’s relentless filibuster of Romney’s Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch, after the passing of Justice Antonin Scalia in early 2016. Romney – and indeed many Democrats (most notably both of Gorsuch’s home state Democratic senators, Mark Udall and Michael Bennet, a point Romney stressed over and over again both in public and private) – thought Gorsuch was a pragmatic and well-regarded pick for the Court. Reid’s stonewalling forced Majority Leader McConnell to invoke the nuclear option for Supreme Court confirmations, and the nomination ultimately passed 58-40. Still, there was bad blood in the air after that point, and Romney couldn’t help but look forward to the minority leader’s retirement.

Something about the election year made him feel restless, too. Though he (not to mention his family) reveled in not having to undergo another presidential primary as late 2015 and early 2016 took shape, Romney couldn’t help but feel anxious about the continuous coverage of the Democratic primary. “Hillary or Joe, here’s hoping for Hillary,” he’d often repeat to his now-Chief of Staff, Ed Gillespie, as Romney initially perceived former Vice President Joe Biden as a stronger opponent (and, for what it was worth, kind of admired his earnestness). Vermont’s Independent Senator Bernie Sanders proved to be something of a spoiler; his passionate base of younger supporters forced both Clinton and Biden to take some positions they’d otherwise prefer not. By the time the Democratic primary debates began, and the candidates were holding more significant rallies, Romney quickly realized his initial take may have been wrong: Clinton could carry a crowd and speak with authority in a way Biden struggled to, and Clinton was outperforming the vice president in collecting superdelegates much more dramatically than even the Biden team seemed to expect. Even before Iowa, Clinton had received endorsements from just shy of 250 superdelegates, whereas Biden had only 90 (Sanders trailed them both, with only 10).

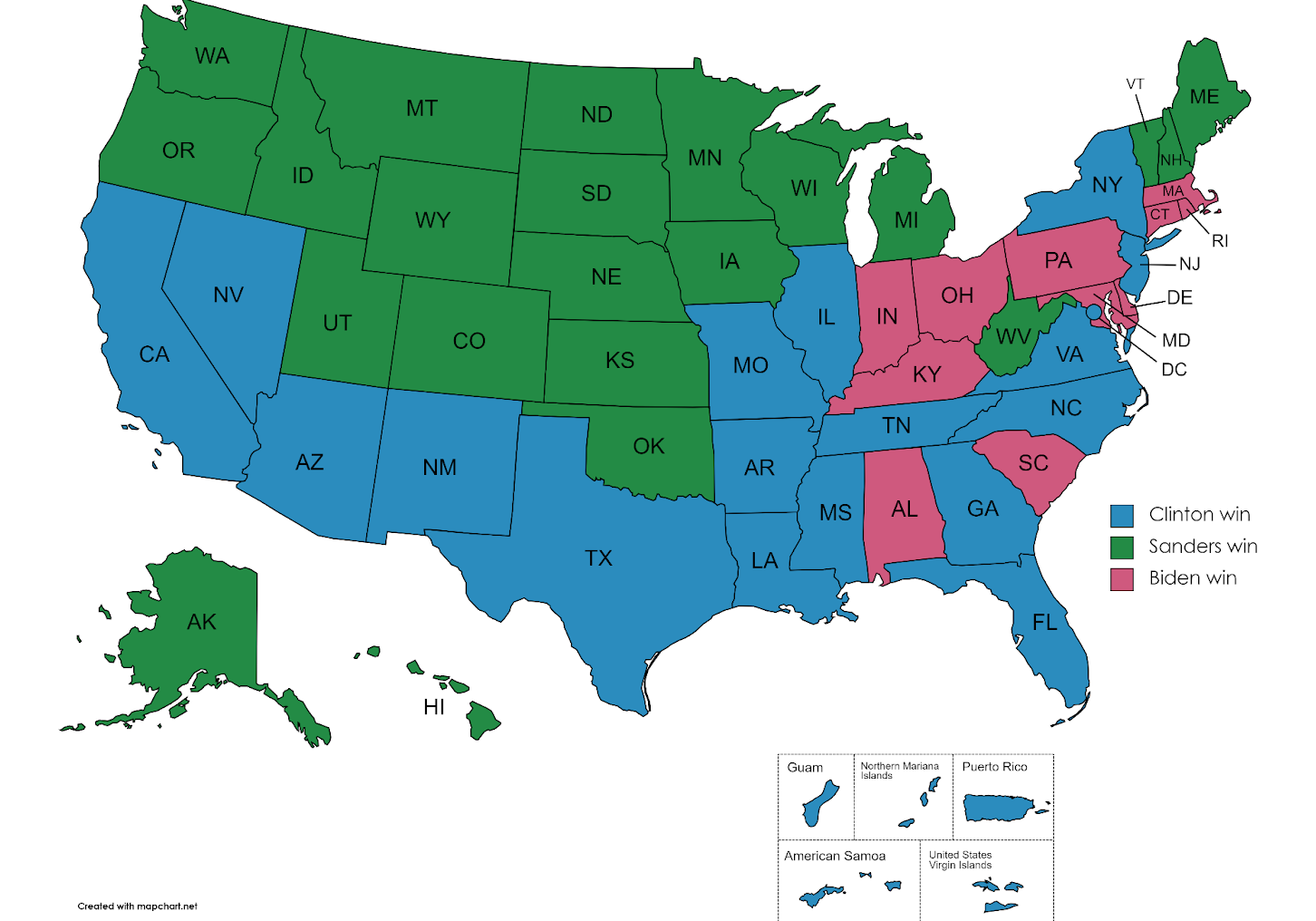

But, by the day of the Iowa caucuses, it was clear this was nothing but an ugly three-way race with potentially no end in sight. National polls would have Clinton up by ten points one week before having Sanders up by five the next; and no candidate could consistently hold more than 40%, let alone 50%, in the polls. Everyone waited with baited breath for the first official results of the 2016 primary, but the anticipation only grew as delays and narrow margins plagued the caucuses. At some point after midnight, it’d become clear that no candidate had won a compelling victory: Sanders carried around 37%, Clinton around 32%, and Biden just north of 30%. Sanders claimed victory while Clinton and Biden sniped at the other, attempting to consolidate their respective bases (though they largely shared support from establishment types, as well Black and Latino voters, which make up small slices of the Iowa and New Hampshire electorates. Some data gurus like those at FiveThirtyEight aptly noted that Biden actually attracted more union-affiliated and rural white voters, which pulled votes away from Sanders’ topline).

A week later, New Hampshire provided little relief. Though Sanders won a compelling 45%, Clinton’s 30%, and Biden’s meager 25% began to prime the party for a long, grueling primary – and no candidate seemed willing to concede. Nevada (39% Clinton, 34% Biden, 27% Sanders) and South Carolina (43% Biden, 39% Clinton, 18% Sanders) only encouraged Biden – who many had written off and encouraged to drop out after New Hampshire – to stick it out. As the primary map progressed, it became clear that Clinton’s base, which was more Latino, Black, and establishment than Sanders’ base, provided the plurality advantage. Biden did well among Black and Midwestern voters generally, but Sanders’ dominance in the Great Plains and Mountain West (and upper Northeast) made it hard for Clinton to get anywhere close to the nearly 2,400 delegates she needed.

By April, Clinton had just shy of 1,000 pledged delegates and 350 superdelegates; Sanders lagged behind with about 800 pledged delegates and 30 superdelegates; and Biden had just below 600 delegates with 120 superdelegates. With only 1,700 pledged delegates left on the table, the tension between the Clinton and Biden camps was palpable as the media increasingly reported on the Clinton campaign’s efforts to get the former vice president to drop out. But Biden – with a notable underdog complex, perhaps made even firmer by Clinton’s bashing – held on, much to the chagrin of the Clinton camp, until the “Acela Primary” in late April, when many Northeastern states would vote. Biden had flagged significantly after his early South Carolina and Alabama romps, but some decisive and well-timed wins in Massachusetts and Ohio kept hope alive enough to power his campaign through to what he assumed would be his natural home: the Mid-Atlantic up through New England. On April 26, when these states all voted, Biden overperformed expectations – carrying all five states that voted that day. This reinvigorated the Biden campaign, which vowed to “go all the way to the Convention, if we have to!” that night, and channeled the energy into a surprise win in Indiana and a very narrow win in Kentucky over the next couple weeks.

During a quiet May, the Biden team went all in on California and New Jersey – by far the largest two remaining primaries. But the writing was on the wall: there wasn’t enough time, nor enough delegates. Clinton had an insurmountable lead – but not enough to have clinched the nomination before the Convention in July. When Biden significantly underperformed in both California and New Jersey, he dropped out and, begrudgingly, endorsed Clinton. Ultimately, most of Biden’s delegates coalesced around the former secretary of State, and Clinton was able to enter the convention with the nomination locked up… but she was tired and bruised by the long primary – and her party was bitter and disgruntled. “Exhausted yet? It’s just getting started,” ran one op-ed in early July. “Democrats Pick a Winner: Mitt Romney,” ran another.

All spring and summer of 2016, the mood around the Romney administration was jubilant. The Democratic contest could hardly have gone better for them (“other than Bernie winning the nomination,” Mitt would often joke), the successful confirmation of Justice Gorsuch invigorated congressional Republicans, and the president and his party – untainted from any divisive primary – had clear eyes about the general election.

It wasn’t until the late summer and the party conventions that it felt real. The Clinton-Kaine ticket struggled to build momentum after what was nearly a contested convention, but were able to hit the trail with piercing attacks on the president. Though they initially attempted to focus on an economic message, the stable and improved economy provided few opportunities, though Clinton hit her stride when she invoked the Trans-Pacific Partnership in her campaign speeches in the Midwest (the Romney campaign, and plenty of soft money interest groups, criticized her flip flopping on the issue). Instead, they settled into a pattern of hammering Romney on social issues – abortion rights, gay rights, and immigration. President Romney considered embracing a more moderate position on all of these issues, but pushback from elected Republicans who were wary of their base put rest to these ideas. It’s not that Romney ran on banning abortion, or gay rights, per se – but his dodging answer of “let the states decide” provided ample opportunities for the Clinton campaign.

By September, it was clear that Clinton could carry a crowd a bit better than Romney – the Democratic base at least saw a vision there – whereas Romney was perhaps a bit more bland and jovial. He was passionate and engaged with his crowds and with Republican voters as he campaigned in Ohio, Florida, Wisconsin, and Virginia, but he wasn’t able to match the zeal or animation of Clinton and her surrogates, who marched out popular actresses, musicians, and Democratic politicians to campaign for her. Still, Romney’s team felt optimistic – he kept even with (if not above) Clinton in the Midwest, many suburban voters and high-turnout educated voters remained in his corner, and there was a clear antagonism towards Clinton within her own party by some of the progressive Left. If Republicans could keep youth turnout in Northern Virginia and in Midwestern cities down on Election Day (something the brooding Sanders campaign had made easier than expected), the Romney path was clear: hold Florida, North Carolina, and Ohio; then snag Virginia or one of the Midwestern states. So, the Republican campaign apparatus was in full swing across the Midwest, seizing on Clinton’s weakness there, and in Virginia – which most figured would once again be the cycle’s most important state.

Clinton proved to be an effective debater, and most pundits credited her with a clear win in the first debate. By the second debate, in early October, a “town hall” style debate where the candidates spoke directly to swing voters, Romney’s stiffer persona really came to bite him; Clinton was more cutting in her criticisms of the president and warmer with people than months and months of ads fed to him for approval about her unpopularity and robotic tendencies seemed to suggest. Fielding a question on how she, as someone who once called some Black youths “superpredators,” would address unwarranted shootings by police, Clinton effectively bashed Romney for attending an expensive fundraiser held by “alleged billionaire” Donald Trump while protests roiled in Ferguson, Missouri in the wake of Michael Brown’s killing.

For the third debate, the Romney campaign was in full panic mode. “Don’t panic. Prepare,” Romney kept telling his team – convinced they were overreacting. So he did, and Romney earned plaudits for his pragmatic responses to questions on the debt and the economy, as well as foreign policy. His team insisted that he attack Clinton on her use of a private email server – which had been a simmering news story for most of the year – and regarding what had happened in Benghazi years before generally, and he seized on the opportunity when he could during the debate. Still, something about it felt a little disingenuous. Nonetheless, the consensus was that Romney won the third and final debate.

In the waning weeks of the campaign, Clinton put a lot of energy into Florida, North Carolina, and Virginia; whereas Romney focused on Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Both campaigns ignored Colorado and Michigan, which they both seemed to think were safe for Clinton (Romney attempted to convince his team that Michigan could be in play, but they talked him down, suggesting his personal history may be biasing his insight as Clinton typically led polls in the state). Most felt the race came down to Florida, Virginia, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Nevada, and New Hampshire – only seven states.

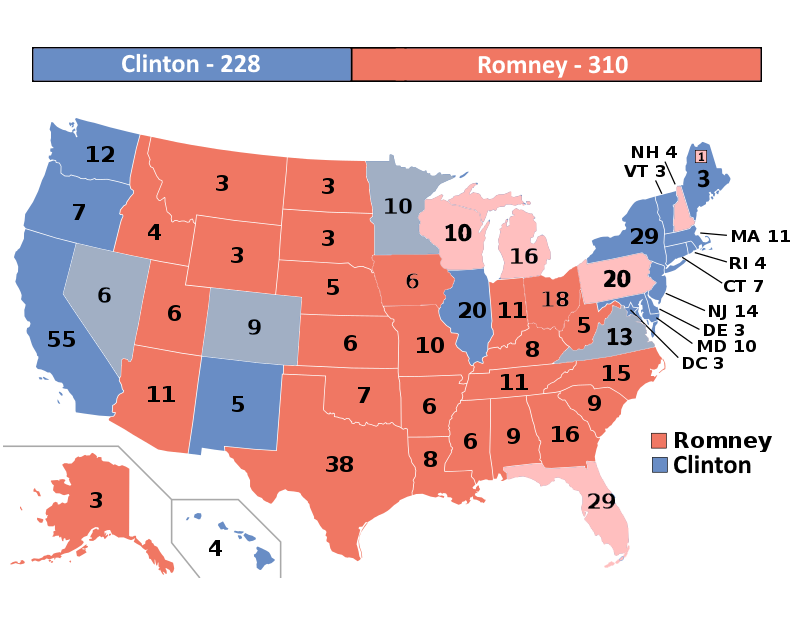

As the polls began to close, Romney perked up – there weren’t a lot of surprises early on, but it was clear Democratic turnout was down as results began to trickle in. Ohio was called relatively early for Romney, though the Clinton campaign hadn’t placed much effort there anyway, and by 9:45 PM the networks called Florida for Romney – dramatically narrowing the map for Clinton, who had put forward great effort over the last week of the campaign down in Orlando and Miami. Of the major states still in play, North Carolina landed in Romney’s corner at about the same time that the networks called Virginia for Clinton. Romney was close – but the Virginia loss threw a lot of conventional wisdom out the window. He felt bullish about the remaining Midwestern states of Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, and something about Michigan remaining too close to call even by 11 PM kept a flicker of hope alive; but Clinton’s victories in Colorado and Nevada – both called a bit before midnight – continued to narrow the map. Clinton had 229 electoral votes to Romney’s 259 as Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin remained too close to call.

By 12:45, early on the morning of the 9th, it was over – Pennsylvania and Wisconsin were called for the president, pushing him well above the 270 electoral votes he needed to win reelection. Clinton conceded that night, and Romney couldn’t help but appreciate the fact that even after what seemed like the most bitter campaign of his life, Clinton’s graciousness signaled something about how both parties could move forward. In his victory speech, Romney thanked the former secretary of State for her service to the country, to the political discourse, and for this campaign, as he called for a “united tomorrow,” and vowed to continue working across the aisle to make sure “America’s great economic and global comeback is felt by all.”

Romney meant it, but he knew it would be seen as mere platitude. Though Republicans held the House, there was no shift in the Senate – his party held on to New Hampshire and lost in Illinois. 51 Republicans to 49 Democrats, again. “At least we won’t have to deal with Reid,” Romney thought to himself at some point on the afternoon of the 9th, but then felt bad about relishing in the retirement of a man who had such a distinguished career, and who he used to be closer to. It wasn’t until some point on the 10th that New Hampshire was called, surprisingly, for Romney. But the highlight of his year, by far, was on November 11th. It was underwhelming for most, as he’d already convincingly won the Electoral College and was expected to win the popular vote by about 1.7%, but for Mitt it felt like a redemption, a sign. He wished his dad could be there to see it: for the first time in 50 years, a Romney had won Michigan.

Once again, we hope you enjoyed this fictional exploration of the world in which Mitt Romney won the 2012 presidential election. This is part three of four, follow on to the next part here.

If you have thoughts, think things would have played out a little (or a lot) differently, or are curious to see an exploration of any other possibilities, please reach out to us, we’d love to hear from you!